Would-be satirists of international development projects must have a tough time when it comes to developing their material.

Some real-life material is so farcical already that it almost defies spoofery.

Neither renowned comic writers Jonathan Swift or Mark Twain could have come up with a better definition of ‘partnership’ than how the word is assigned meaning in development projects as a set of activities developed in isolation from the country in which such activities are to take place and which is funded entirely by one of the ‘partners’.

Or the political economy analyses that get commissioned and shelved because, er, they delve too deeply into politics and the economy, thus preventing them from being shared with ‘partner governments’.

The fact that ‘adaptive management’ necessitates a long manual which cannot be deviated from is another personal favourite.

Good satire can make for powerful writing. Making irreverent observations about human eccentricities and bureaucratic inconsistencies in a humorous and entertaining way can force us to confront ourselves, the organisation we work for and the system of which we are part.

But this type of writing can be a lonely and perilous calling.

Juvenal – considered to be the first satirist – was exiled from imperial Rome for wielding his pen a bit too cleverly, living out his final days in penury because he skewered so effectively the affections and hypocrisies of the powers-that-be.

This might explain why there’s so many snarky eye-rolling messages amongst people who work in aid and less examples of such candour being on the public record.

Those who have the courage to write engagingly and with a sense of the absurd about serious issues that they care about deeply are people I admire tremendously.

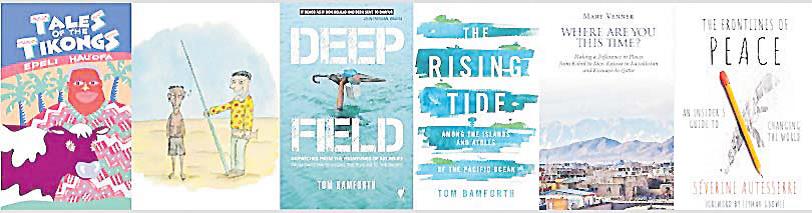

One such contemporary writer is Tom Bamforth whose Deep Field, about humanitarian aid, and The Rising Tide, about the Pacific, are gently stinging explorations of some of the inner incentives of the development game.

Mary Venner’s droll memoir about the advising trade is amusing and insightful in equal measure.

My enjoyment of Severine Autesserre’s work is enhanced by her rolling her eyes at some of the antics she encounters, such as telling the story of a Congolese counterpart in the Congo who pretended to be Puerto Rican in order to get taken more seriously by his international peers.

Two short but powerful books of more olden vintage — both out of print but available with a bit of ferreting around — show that such ironies and contradictions are nothing new.

I enjoyed their amusing observations tremendously. The first is Tales of the Tikongs by the late Tongan-Fijian writer Epeli Hau’ofa. Hau’ofa is best known nowadays for his academic work which straddled anthropology and post-colonial theory.

His ‘less serious’ writing is seriously entertaining and equally profound.

His tales is set on the fictionalised Pacific island of Tiko — could be Tonga, could be Samoa — in the years immediately after the Union Jack has come down.

Published in 1983, it comprises a set of 12 short-stories which excavate the burlesque and sometimes bawdy antics of the Tikongs and the donor set that live within their midst.

Not all the humour lands but when it does the book is very funny indeed.

There is much that is timeless in Hau’ofa’s descriptions.

When I screenshotted and sent out a few paragraphs that revolve around one of the book’s characters going to a ministry only to discover they everyone who should be in the office is overseas at a conference or training program, I got an immediate reply from a friend toiling as an adviser in Papua New Guinea: “Reads like a pre-COVID day in the office to me!”.

Hau’ofa gives technical assistance — as ubiquitous then as it is nowadays — a gentle ribbing too. Advisers grouch about nepotism in Tiko’s public service but have cognitive dissonance that it was personal connections which won them their own jobs.

And he’s on-point with the bewildering bureaucratese of this business and its hidden hierarchies. When Ole Pasifi kiwei (many of the characters have wordplay surnames) tries to secure funding for a project of cultural preservation, he’s told by Mr Minte that he needs to write a long funding request and form a committee. Ole asks for a typewriter to do so but the punctilious Minte refuses.

“Once politicians see that we’ve given a typewriter for cultural preservation, they will start asking awkward questions. What’s a civilised typewriter to do with native cultures?” Minte retorts.

The whole experience leaves Ole ‘disturbed and reduced’ but as the story wears on he becomes adept himself in the ‘twists and turns of international funding games’ and becomes a bit of an entrepreneur, milking multiple funding udders for projects with ‘aid-worthy objectives’. It’s reminiscent of the final scenes of Orwell’s Animal Farm.

Another playfully provocative satire is Oren Ginzburg’s The Hungry Man from 2004. It’s a short ‘kid’s bedtime story’ sized book structured around that old development saw of ‘If you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day; if you teach a man to fi sh, you feed him for a lifetime’. The book follows an unnamed and earnest-faced bespectacled male development worker teaching the eponymous hungry man how to improve his lot.

Each page juxtaposes a ubiquitous development phrase with a comic illustration.

So the phrase ‘train the trainers’ is accompanied by a picture of an earnestfaced development worker talking though a bewildering diagram with boxes and arrows going hither-and-thither to welldressed but perplexed ‘local trainers’ as the hungry man stands bewildered off to one side. ‘Advocacy’ is presented as welldressed Westerners clinking champagne flutes at the ‘hungry man’, and the picture to illustrate ‘suitable mainstreaming of gender’ could be a pictorial rendering of me when trying to write the ‘GEDSI’ section of a six-monthly report.

I Googled Ginzburg to see who he was.

Turns out he’s a wonk himself, one who has carved out a decent career working for various international agencies.

He’s presently in Myanmar with UNOPS (United Nations Offi ce for Project Services).

Writing satire didn’t do him any harm.

Thus, there might be more room for comic reflection about uncomfortable truths than all the screenshotters fear. That’s a very good thing. It would be lovely to see more exponents of this genre of humorous but powerful and deeply-motivated type of writing.

- GORDON PEAKE is an affiliate of the Center for Australia, New Zealand andPacifi c Studies at Georgetown University, and author of the award-winning Beloved Land: Stories, Struggles and Secrets from Timor-Leste. He is presently finalising a manuscript recounting his time living and working in Bougainville. The views expressed are his and not of this newspaper.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.