On the night of August 5, I was restless and could not sleep. I turned the light off, tossed and turned, then put it on again. This happened several times.

I was thinking about my friend of more than 50 years, Mohammed Apisai Vuniyayawa Tora.

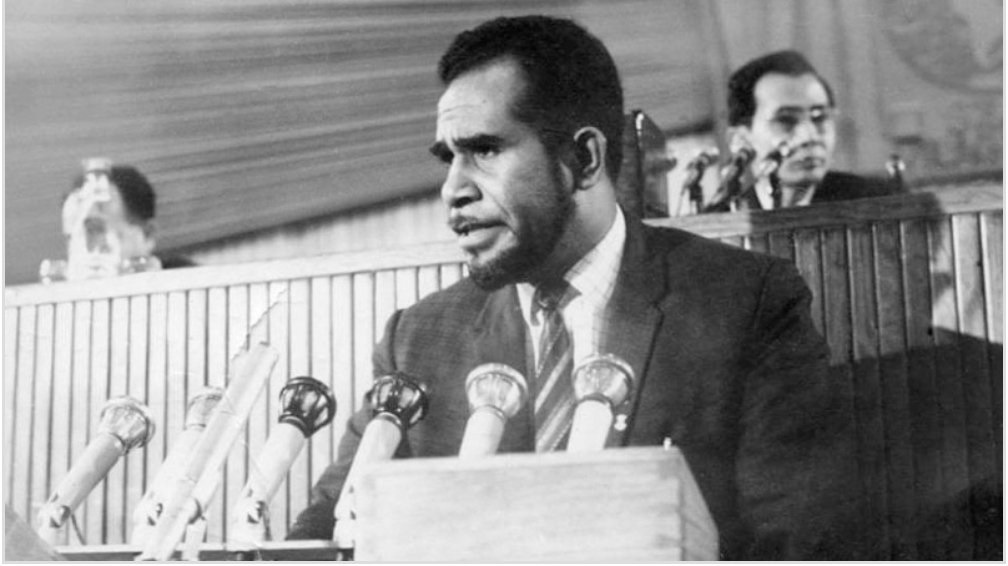

He was acknowledged as one of the most influential and controversial figures in Fiji’s history. Apisai was hated and reviled, loved and admired.

Depending on your viewpoint he was either a courageous champion of the workers and the people, committed to a future for Fiji of co-operation and multi racialism.

Or he was evil personified, a racist and a spoiler, intent on overturning the established order and promoting indigenous sovereignty.

Apisai, 86, was terminally ill with cancer at his village of Natalau in Sabeto; I was struggling to find the thoughts and words for a commentary on his storied, turbulent life. He knew I was going to do this.

How did one write about a man like Apisai? How would I define and describe him? He was a mass of contradictions; so complex, so unpredictable, so different.

I remembered a quotation about Russia by Winston Churchill: A riddle wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. Yes, that came close to what I wanted to portray. But only close. It did not capture the whole man. I wasn’t confident I could do it in a relatively short piece summarising circumstances and events of half a century.

The time now was about 1.30am on August 6. I tried to sleep again.

I did not know that Apisai’s condition had worsened. He was readmitted to Lautoka Hospital, and had slipped into a coma. Perhaps his spirit, preparing for something, had kept me awake. His son and caregiver Livai told me from the hospital next morning about Apisai’s ominous relapse. The plan was to take his father home for his final days on completion of a series of blood transfusions. But he never regained consciousness and died in hospital at approximately 2.30 on the afternoon of the sixth.

My wife Emelita had asked Livai to whisper into Apisai’s ear that we loved him and so did our friend and his, Davina Kaitu. Livai should whisper to him as well that our mutual friends Mick Beddoes and his wife Eileen also sent him their love.

We were all members of a small group of Apisai’s closest friends, along with Len Anthony, who lives in Sydney, and visits regularly.

Apisai had been preparing for his death. He was very weak.

He kept asking, ‘When am I going to die’? For about a week he instructed Livai every night to put the entire lounge and bedroom into total darkness.

This would heighten his senses and remove distractions as he readied himself for the end.

Emelita, Mick and I last saw Apisai on July 14 at 4pm. That was the time he had designated for our visit to him at Natalau. Apisai was always a stickler for punctuality.

Livai pushed him in his wheelchair into the spacious lounge, with its beams bound by sinnet and ceiling areas adorned with artifacts. Apisai, barefoot and wearing a printed sulu vatoga and crisp shirt, was smaller and thinner than previously.

His face was drawn, his skin seemed paler but his eyes were clear. He was pleased we had come and welcomed us in a low voice. We cast aside virus self-distancing in a surfeit of social kissing. I kissed Apisai’s hand. He took Emelita’s hand and kissed it. Mick kissed his cheek.

Livai, looking professional in blue hospital-style scrubs, withdrew. We commented on how good he looked as a medical orderly. Apisai said he thought Livai’s appearance was weird, presumably because he disapproved of his long, coiled dreadlocks.

We talked about many things. Some memories produced smiles and laughter. Apisai had been briefed thoroughly by his doctors on his condition and the likely time left to him.

Well now he knows I thought. He’s been waiting for this for a long time. Always saying he no longer served any useful purpose despite our protestations that he was wrong.

Apisai asked us, as his friends, to prepare a newspaper sympathy notice for insertion at the time of his passing. Keep it simple, he said. Mick intervened: How can we keep a notice like that simple when it’s about a complicated person like you?

That’s right, I said. You’ve always been a man of contradictions. Maybe that’s why we love you.

I chose one example to underline the point: Look at how you railed against colonialism, but had so much love and respect for Queen Elizabeth, head of the very colonial power that suppressed you. It doesn’t make sense.

I still respect her, Apisai said, pointing to a large formal picture of a young Queen with Prince Philip high on the wall just above where he sat.

The only other large portrait photograph displayed in the room was that of his late wife, the beautiful Adi Melania Ganiviti of Bau, who died in 2006.

He still grieved her passing. His broken heart had never healed. One of the reasons for his constant yearning for death in his last years was that he wanted to be reunited with Viti.

We continued to converse but noticed that every few minutes his eyes would close and stay that way for 30 seconds or so. The conversation would stop, resuming when he opened his eyes. Apisai was exhausted by his illness; very drained.

But he became instantly animated when Mick asked whether he would change his life if he could live it again. “Absolutely not. I would change nothing.” His voice was slightly louder and firmer.

Apisai then murmured that someone should say Grace before afternoon tea. Mick nudged Emelita. This would be her job. But Apisai looked at Mick. “You this time,” he said.

Mick gathered his thoughts quickly; offered thanks for the food and Apisai’s life and for the opportunity for us to be together again.

After tea and more chit chat, Apisai declared “your time’s up.” He was usually never one for prolonged socialising.

We said our farewells and left, happy to have met him again. Mick and I were certain we would be back to spend more time with him. Emelita felt we would not see momo again.

I can clearly recall my first contact in 1966 with this extraordinary man when I was a staff reporter on The Fiji Times. I was assigned to cover a gathering of workers at the Suva Market area. They were reportedly in a restive mood, discussing a simmering industrial dispute. Apisai Tora, the menacing stirrer, was the central figure so anything was possible. I knew of him and his reputation but had never dealt with him face-to-face.

On this morning I needed to talk to him personally to get the facts.

There was a big crowd in the vicinity of the market and adjoining bus stand. I asked someone where Mr Tora was. He was apparently holding court in the middle of the throng. I edged my way forward trying to pinpoint his location.

Some of those gathered must have recognised me as a The Fiji Times journalist. I heard uncomplimentary mutterings about the paper that was seen as anti-worker.

Then I spotted a figure who appeared to be the centre of attention. This must be Mr Tora. I pushed forward; there was more muttering about the The Fiji Times. I was now about six feet from the union leader. He was of medium height.

I think he was wearing a Fidel Castro-style peaked cap and smoking a cigar. In the early 1970s he would personally meet the Cuban revolutionary, in Havana. Castro arranged for Apisai to get a regular supply of Cuban cigars.

As I got closer it was difficult to move as I was hemmed in on two sides. I introduced myself and said I wanted to take notes on the meeting and its purpose. Would he mind answering some questions? Mr Tora was expressionless and silent. Not friendly.

I asked: Would it be construed as a hostile gesture if I slowly moved my left hand to my back pocket and gradually pulled out my notebook? As I was speaking, my hand was going to my pocket. It gradually freed the notebook.

I also asked whether it would it be seen as a hostile gesture if I slowly removed my pencil from my shirt pocket, so I could take some notes. The pencil came out of the pocket, nice and easy. I was ready to conduct an interview.

Mr Tora looked at me quizzically, eyes narrowed. He waited a few seconds. The crowd watched him and me. Then he smiled: ” He’s OK,” he called out. “Go ahead, ask your questions.”

So I did and got my story. An enduring friendship was in the making.

At 2 in the afternoon I was at the police station for the daily press briefing. Superintendent Wally Caldwell said to me:” You did something stupid this morning going to interview Tora in the middle of that crowd. You were at risk, it could have been dangerous.”

“Well I had to get the story and needed to interview him. That’s what I did and I got what I wanted.”

I next met Apisai at Sigatoka magistrates’ court when, as secretary of the Hotel and Catering Workers Union, he was charged with the burning of part of the Korolevu Hotel on the Coral Coast. He appeared as a remand prisoner at a preliminary inquiry.

During the mid-morning adjournment he called out to me from the dock: “How are you mate?” I wasn’t sure of legal protocols governing conversations with prisoners, so I didn’t reply, but just acknowledged him with a smile and nod.

I felt some of the preliminary evidence against Apisai was a problem for him. But he was eventually acquitted. He spent several months in prison on remand before being declared innocent. He thought that was an injustice.

Apisai Tora emerged into the public eye in the 1959 oil workers’ strike in Suva that culminated in rioting, rocked the colonial government and frightened many citizens. The turmoil grabbed headlines in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. One Suva letter writer described what happened as “shattering ” and “complete chaos”.

Apisai, then 25, joined James Anthony, from a well- known Suva family, in organising the strike and liaising with the strikers. Mr Anthony had approached Apisai after reading a letter by him in the prestigious international Time magazine. The Natalau native described Fiji as a “white man’s paradise and a black man’s hell”. It was interesting to me that he had managed to get a letter into the pages of Time. That was no mean feat. He still subscribed to the magazine at the time of his death.

The ’59 disturbances gave Emelita her introduction to this dangerous provocateur. An eight-year-old pupil of St Joseph’s Convent, she and two older sisters were quickly making their way in the afternoon to the family house in Struan St, walking distance from the city centre. The Sisters of St Joseph had hurried the students off home because there was talk of “trouble in the streets”.

When the Wendt children reached Burns Philp store they were conscious of more men than usual on the streets and street corners. As they were about to turn into Nina St they heard the sound of marching boots on the double.

Emelita turned to watch in a combination of fear, excitement and fascination as a squad of men in khaki uniform, wearing helmets and carrying guns, came over the Nabukalou Creek bridge.

In front of Burns Philp the squad turned left towards the Suva Wharf. It’s more than likely they were on their way to provide protection for the oil tanks belonging to the Shell Company, the focus of the strike.

People scattered and began running everywhere. Many young men made for Nina St and Emelita began running with them, dropping her little cardboard suitcase on the ground in the panic.

Her two sisters shouted for her to hurry. They ran the rest of the way home. The Wendt girls watched from the safety of their verandah. They heard the sound of cracking glass as rioters stoned the windows of the Health Office on Rodwell Rd opposite the Shell Company tanks.

That night all unnecessary lights went off and there was a curfew. Emelita heard her parents talking in the gloom about the leaders of the strike, this James Anthony fellow and his accomplice Tora.

Mr Wendt also wondered about the safety of his brother-in-law, one of the European managers at Shell. It wasn’t long before he privately began to perceive Apisai as someone who wanted to help the workers.

The Tora name would come up again in Emelita’s life when she was about 13 and he was involved in a major transport workers strike. Schools closed early (much to the delight of a lot of students – “thank you Mr Tora”) because buses weren’t running.

Thirty or so years later she would meet the firebrand himself face-to-face. We were graciously hosted by Apisai and Adi Ganiviti to a private celebration of our marriage at the Tora home at Natalau Village. My late mother Kathleen from England, was with us.

Towards the end of his life, when we had relocated from Suva to Nadi, Emelita began to hold a special place in Apisai’s affections. We saw him frequently. He referred to Emelita as his sister and always asked about her health and wellbeing.

Before Apisai’s debut as a controversial unionist, he had two experiences that would profoundly impact his career and attitudes. From 1954 to June 1956 he served as a soldier with the 1st Battalion, Fiji Infantry Regiment in the campaign against communist insurgents in Malaya.

Young Tora was a storeman in the mortar platoon, a team leader, and a scout for jungle patrols. The sound of mortar shells left him partially deaf.

The treatment Apisai and his compatriots received after their return to Suva helped turn him into a radical and a dissenter. They had been assured the government would assist them in every way possible after demobilisation.

Following a tumultuous welcome in the capital city, the men were later told to report to the Town Hall. They formed a long queue and, one at a time, each was given a pair of long white trousers, a white shirt, a digging fork, a cane knife and file. And that was that.

Apisai was angry and disillusioned. “Our integrity was insulted when we were sent back to our families with some left-over farming implements and white shirts and trousers for God’s sake. We were treated like shit.

Of course the officers fared better than we, the ordinary soldiers. We had signed on for Queen, vanua and country, and this is how we were thanked. It was like a con job.”

He complained to a senior military leader, a chief, only to be met with curt indifference.

He had noticed something else on the Malaya campaign. In Singapore, just across a causeway from Malaya, the Fijian soldiers were permitted to socialise and drink at Singapore’s normally all-white Union Jack Club and the Britannia Club.

At home they had to try to get a permit to buy and consume drinks in certain places open to Europeans. It was stark discrimination.

In Malaya Apisai had also gathered initial impressions of the Muslim faith, some of its rituals and manner of worship. He had told me he was impressed to see worshippers kneel with heads bowed close to the ground. To him, this meant they were giving their all – body, mind, soul and spirit – to God.

He mused that when Fijians went to church they sat on benches. But when they were in the presence of a high chief they got down on to the floor. “God is the biggest chief and yet before Him we are sitting on the church benches not prostrating ourselves.”

One day at the government office in Nadi where he worked, Apisai met Mr Mohammed Ramzan Khan, a businessman who had come to pay his land rent.

They began to chat. Mr Khan asked Apisai whether he knew anything about the Muslim faith. Apisai recounted what he had observed in Malaya.

Mr Khan volunteered to tell him more and gave him his address and telephone number. Apisai called him after work the same day. Mr Khan became his teacher and Apisai converted in 1957, taking the additional name Mohammed. He was 22-years-old and undoubtedly Fiji’s first indigenous Muslim.

The reaction of his parents was not good. His mother Nanise wept. She felt betrayed. His father, Kalaveti, policeman and disciplinarian, did not speak to his son for a month. Later on he told Apisai he had made his mother very unhappy.

But as far as he, his father, was concerned “you and I serve the same God, but the worship is different. You go ahead, I am with you”.

When in 1974 Apisai acceded to the chiefly title of Taukei Waruta, yavusa Waruta, he had to navigate a careful course between what he saw as his obligations as a traditional leader and his commitment to Islam.

It was evident that as chief he had to identify totally with his clan, their traditions, beliefs, needs and expectations. So every Sunday he was part of the congregation at the village Methodist church. To decline to attend was unthinkable.

And of course he served the same God as his people. At the beginning of his career, Apisai found himself facing-off against the colonial power in an astonishing way when he got a civil service job as a clerk.

One morning his boss, the Englishman Harry Halstead, a district officer, arrived at the office as Apisai was engaged in finishing a task to deadline. Mr Halstead ordered him to mix some yaqona. But Apisai went on working.

Again he called out, “Tora, lose,” start mixing. Apisai stood up and declared that civil service general orders did not say anything about mixing yaqona for district officers. He was not paid to do that.

If his boss wanted someone to mix a bowl, he could “lai tukuna vei bubu” (go tell your grandmother.) Mr Halstead, who unknown to Apisai could speak Fijian, stormed out of the office. He thought Tora had gone mad.

The upshot was that Apisai had to appear before a medical board that would determine whether he was psychologically fit to carry out his duties. This young man with an attitude was certified to be mentally sound.

But he nonetheless lost his civil service job. Karam Ramrakha, a senior member of the National Federation Party, was to pronounce some years later that Apisai’s refusal to mix the yaqona was an important step on the road to independence.

Before Apisai’s stint as a public servant he met a certain high chief who would reach the pinnacle of political power and become the first elected Prime Minister of Fiji and then President. Their destinies would be intertwined.

Apisai was assisting with a recruitment drive for territorial soldiers when Kamisese Kapaiwai Tuimacilai Mara came to his desk as a volunteer.

Recruiting clerk Tora did not know this tall, good-looking man. But he asked him the required questions and began writing down his personal details. When the stranger mentioned he was a district officer, Apisai figured he was someone important.

He excused himself and left the room. Lauan men waiting outside confirmed to Apisai he was talking to a paramount chief of their province and he should be sure to follow proper protocols.

Apisai returned to his desk:

“I’m sorry Sir, I didn’t know who you were.”

“Don’t worry soldier, just carry on and do your job.”

Ratu Mara would later offer Apisai a position at his office in Ba. He was so impressed with his work that he awarded him a double pay increment.

After his untimely exit from the civil service following the yaqona insubordination incident Apisai found his way into the infant union movement. He sensed unionism was not only a vehicle for achieving justice for poorly paid working people but could also be an instrument for wider change.

As a reporter I met him from time to time on the news rounds. He was like a permanent story. I became more and more intrigued by this contrarian, terror of the business world, perceived general trouble-maker, constant occupier of headlines.

We spoke often and I discovered he had a dry humour, was well read and well-informed and could discuss just about any topic. From time to time we met socially. A friendship formed, but I had to remind Apisai that I was a reporter.

That meant I would have to ask him for comment sometimes on issues he preferred not to talk about, or be quoted on. It would be better on occasion if he didn’t confide in me about controversial newsworthy matters.

When I received information on the matter at hand from another source I would let him know, while keeping the informant confidential if necessary. I stressed that Apisai couldn’t expect any journalistic favours because we were friends. He understood the rules.

When I left The Fiji Times to set up my own public affairs consultancy, the situation changed. I was no longer a news reporter, so a constraint to our friendship was removed. However, I had to maintain a balance between my obligations to my commercial and other clients and my friendship with someone many of them disliked and even feared.

I accidentally overhead a top businessman telling a colleague that he had tried to warn me about Apisai, but I wouldn’t listen and still spent time with him. Others recognised there might be merit in their public affairs consultant having a sound relationship with this demon.

They were right. I did not find it difficult to talk to him on contentious issues affecting business. He knew I had a role to play that might conflict with his position.

From time to time, however, Apisai made me angry. One episode serves to illustrate this. As a unionist he was a central figure in a period of industrial strife at Nadi airport. It involved a confrontation with the Australian airline Qantas, which had a predominant role in airport management and operations. I thought Apisai was running amok.

He kept using his influence with the workers to close the airport, causing damaging disruption to tourism and the entire economy. I said to him afterwards that I had the sense that if he woke up in the morning in a bad mood, he would simply decide to shut things down until he felt better. He retorted he was just using whatever power he could muster to get the best conditions for his members.

One day, with the airport out of action again, I’d finally had enough. I fired off an angry telegram to him. I can’t remember the actual words, but the message was along the lines of “STOP CLOSING THE AIRPORT ON A WHIM. YOU’RE HURTING THE COUNTRY. JUST STOP IT! THERE’S GOT TO BE A BETTER WAY!

Apisai did not reply. But the airport reopened the next day.

When he was flirting with socialism and communism, he used to mention Russia a lot. It was during this time that he bestowed upon me a Russian version of Wilson. As I write this I am looking at a postcard he sent from India addressed to Comrade Matt Wilson. His message hailed me as Comrade Wilsonavitch.

Apisai’s career was to be marked by frequent periods looking at the bars in prison cells. He said he had lost count of the times he’d been sent to gaol. He contended that many of his convictions were for offences against laws he considered unjust and oppressive or touched on “political” issues. Some of his transgressions related to what he saw as violation of sacred cultural boundaries. For example, he asserted that a quarry at Lomolomo was on sacred land of the tua lei ta, the route followed by the first Fijians from Vuda, when they trekked across Viti Levu. Apisai and a group of men closed the quarry; machinery was damaged. He contended a structure in Sabeto was on the tua lei ta. He burnt it.

I visited prisoner Tora several times. The first was at Korovou Gaol. We talked as usual under the supervision of wardens. I cannot remember the content of our conversation, but I can never forget what Apisai said when I was saying farewell.

“Do me a favour will you?”

“Of course, if I can.”

“Don’t visit me again.”

“What? Why are you saying that?”

“I don’t want to you to see me like this.”

Apisai was dressed in a prison shirt of coarse blue cloth, and shorts of the same fabric. He wore big black boots. No socks. His head was shaved.

I said he was a prisoner. It didn’t matter to me if he wore prison garb.

But it mattered to Apisai, because I was there.

I didn’t have to revisit because he was released not long afterwards.

On another occasion, some 45 years ago, I went to the Korovou prison when Apisai was once more incarcerated. It was the morning an eight year-old child knocked on the main prison doorway demanding to see him. This was my daughter Leanne who knew Apisai well from his stays with us when he visited Suva. She was scheduled to fly out to Auckland next morning to rejoin her mother.

A prison warden had earlier refused entry to me as visiting time was over but Leanne wouldn’t have it. She knocked and knocked on the prison gate. Finally it opened and a warden peeped out. The little girl demanded to be allowed in to visit her friend Mr Tora before she went back to New Zealand. The bemused warden was hesitant. The child kept demanding. He vanished back into the prison. The child started knocking on the door again. The warden appeared.

“OK, you can see Tora and so can your father.”

We waited a few moments in the visiting area. Apisai, in the same blue prison garb and shaved head, entered.

“Mr Tora!”

“Leanne! Well I’ll be doggone. How did you get in?”

“The man wouldn’t let Dad through. But he agreed when I asked.”

There were embraces all round. It was a happy reunion in unhappy circumstances. The farewell was tearful.

Over the years Leanne kept in touch with Apisai. In 2013, as chief of Natalau, he led formal ceremonies accepting Leanne and her daughters, Penelope and Bianca, as members of the village.

I think the last time Apisai ended up in prison was when he organised a roadblock on the Queens Road near Natalau. It was supposed to exert pressure for Ratu Josefa Iloilo of Vuda, to be appointed president.

Apisai had hinted to me the previous night that something was in the offing, but I wondered whether he was just being dramatic. He wasn’t, so back to prison he went.

Emelita and I visited him at Natabua Gaol. He had a neat cell to himself with a small verandah. We sat talking, sipping soft drinks and eating grapes we had brought. We had the impression the staff considered it an honour to be hosting this famous man of the West.

I cannot sketch in here the complex details of Apisai’s political and parliamentary career. That was not my purpose. But I will touch on one or two aspects and personal experiences.

Suffice to say Apisai was a political animal. He loved the theatre of politics; the drama, uncertainties, the plotting and intrigue. He frequently claimed that generally he didn’t trust anyone, including himself! I think he said that just for effect.

Apisai served in Parliament as a member of the National Federation Party Opposition and became a devoted follower of Siddiq Koya who succeeded A D Patel as leader. Apisai thought Mr Koya was astute and able.

He reminisced that Mr Koya could speak in Parliament for two hours without notes. I accompanied Apisai one night in Suva on a visit to the apartment where Mr Koya was staying. The Opposition leader wore a sulu and white vest.

We hung out for a couple of hours sipping scotch and water and dissecting Fiji’s political situation.

For Apisai, however, Ratu Mara, the prime minister, was the supreme politician. He had powerful mana, and a good mind, was an excellent organiser and strategist and an effective debater. He had a wide range of contacts in all sectors of the community.

The two of them went back a long way – to the time Apisai took notes about the personal details of the high chief in the 1950s as part of an army territorial recruitment campaign. Then of course Ratu Mara had given Apisai a double pay rise when he worked for him as a clerk.

In 1979 Apisai called me from Nadi saying he wanted to join Ratu Mara’s Alliance. Would I tell the PM and find out about procedures to follow?

I was ready to help, but wondered whether I would become party to placing a time bomb in the government.

I called Ratu Mara and told him he had a new recruit. We chatted about Apisai and then I asked: where to from here? Ratu Mara wanted Apisai to deal with Cabinet Minister Jonati Mavoa on the details and timing for his admission to the party. All went well. Apisai behaved, and did not explode. He became a valued member of the Alliance and, from memory, won two elections.

He served as Minister for Works in Ratu Mara’s Interim Government following the 1987 coup. Ratu Mara described Apisai as one of his hardest working ministers.

In perhaps 1990 or 91, Apisai asked me to come to his ministerial office in the Post & Telecom building in Central Suva. I arrived on time and we spoke about a speech he wanted me to draft. As I was leaving I complimented him on the cut and style of his shirt. He stood up, unbuttoned it, took it off and handed it to me.

“Here, it’s yours.” I reciprocated by shrugging of my shirt and giving it to the bare-chested minister. Apisai’s secretary looked at me oddly as I walked through reception wearing her boss’s shirt.

Things got complicated when Apisai teamed up with Mick Beddoes and a multi-racial group in the west to contest the 1992 election. They had formed the All Nationals Congress (ANC). By then I was a vice president of the General Voters Party (GVP).

We would have to compete against the ANC. This meant I would be going against Apisai. I complained to him that his latest move made us head-to-head political foes.

We agreed we would campaign strongly but with civility. We would preserve our friendship. That’s what happened. When the votes were in, Apisai did not win.

In his political journey Apisai had also publicly identified with Fijian nationalism, especially the Taukei Movement, which became a force in the 1987 coups. So what was he? A believer in a multi-racial democracy? An advocate of Fiji for the Fijians? Or a supporter of a hybrid of both?

When we relocated to the West in retirement seven years ago, Apisai was delighted. He came to our house with a contingent from Natalau and performed a full ceremony that incorporated us into their tokatoka.

Now our bond was even stronger. We met as often as possible sometimes at his place, occasionally at ours, and often at LCs restaurant or other venues.

We exchanged books, many of them on World War II. He had a special interest in Hitler and his generals. Then I discovered his mother had Teutonic ancestry.

She was a Schmidt and a quarter German. He was in the habit of suddenly giving me the Nazi salute and calling out Sieg Heil! It was obviously his joke, Apisai being Apisai.

For some perverse reason he had a liking for Donald Trump. I lent him my copy of the bestseller about this disaster of a president, A Very Stable Genius by Carol D. Leonnig and Philip Rucker. He didn’t like it and tossed it aside.

The last book he read was The Silk Roads – A New History of the World, by Peter Frankopan. He told me it was heavy going but was determined to finish it. And he did, as his illness was quickening. I borrowed the tome. It is heavy going, but the research is impressive. I’m also determined to finish it.

I’m not sure I ever fully understood Apisai. Perhaps that was beyond me.

But he was my friend, with all his flaws and virtues, and I loved him.

- Matt Wilsoni is the cofounder of Communications Fiji Ltd, a communications consultant and a former reporter of The Fiji Times. The views expressed are the author’s and does not reflect the views of this newspaper.