In the mid-1800s, the first reports of cannibalism in Fiji emerged in England.

This happened through the writings of missionaries.

Despite its many truths, there was a lot of scepticism over the brutal act.

Naval officers who had visited the Fiji group on ships had seen nothing of the practice.

They never lived among the natives like missionaries.

So as soon as the existence of cannibalism was proven, there came a barrage of reaction.

“However, this reaction was based on exaggeration if not underestimated,” noted anthropologist, Basil Thomson, in “The Fijians — A Study of the Decay of Custom”.

According to Thomson, a university academic, Professor Archibald Sayce, had made a “ridiculous assertion” that the Fijians ate the flesh of their aged relatives – an act which the indigenous people themselves found horrifying.

“To eat, even unwittingly, the flesh of your relation, however distant, or to eat or drink from a vessel used by a man who had done this, would result, so the Fijians believe, in the loss of all your teeth,” Thomson said.

The bodies of real or potential enemies were hardly eaten, except in rare cases.

If ever bodies were consumed, these were captured and slain enemies in battle, or cast away in wrecks “with saltwater in their eyes.”

To the early Fijians, the bodies of those who died had to be buried, though there were rare recordings of the “secret desecration of graves for the purposes of cannibalism”.

Even if this happened, they were very rare, and treated with disgust.

Morality of cannibalism

Thomson said there appeared to be a number of traditions that talk about the origin of cannibalism in Fiji.

Among them were the rituals associated with worship.

History records show that human bodies were the most valuable offering that could be sacrificed to the gods.

And because presentations of food were eaten after they were offered to deities, the human sacrifice was treated the same way.

It was a “tabu” for a person of low status to decline food offered to him by a chief.

In some places, if a slave could not eat a cooked yam presented to him, he would wrap it up and took it home with him to eat at a future meal.

If he threw it away, he had to do it secretly so as not to offend the donor.

In 1853, a Somosomo chief, in reply to a missionary’s complaint, said, “We must eat the bodies if Thakombau gives them to us.”

Thomson said this obligation to eat human flesh was “tenfold stronger” when it was a “requirement from gods themselves”.

Hence, eating human flesh was not done indiscriminately as many believe.

Rather, it was practised during ceremonial sacrifices such as those held to celebrate a victory in war, the launching of a chief’s canoe or the building of a temple, et cetera.

Thomson said cannibalism may only have increased alarmingly about the end of the eighteenth century.

“In the Fijian mind it was but a step from offering gifts to a god and taking them to a high chief, and great feasts soon came to be considered incomplete without a human body to grace the meal,” he said.

Among a few of the chiefs there began to grow a “vitiated taste for human flesh”.

Human flesh was “tabu” or not allowed to be eaten by women. However, the women of rank from Bau were said to have indulged in it secretly.

Except in moments of excitement, the cooked flesh was shared out with elaborate ceremonies, and eaten only in the privacy of the house.

The practice was concealed from Europeans, partly due to the knowledge that it would excite contempt.

The “tabu” and ceremonies surrounding it indicated its religious origin, Thomson suggested.

Every part of the body was given names connected with cannibalism.

“The trunk, which was eaten first, was called Na vale ka rusa (the house that perishes); the feet, Ndua-rua (one-two),” Thomson said.

Act of vengence

English anthropologist, Sir Edward Burnett Tylor gave six reasons for the practice of cannibalism.

They were famine, revenge or bravado, morbid affection, magic, religion and habit.

Three of these had no application in Fiji, according to Thomson.

Therefore, religion, revenge or bravado, and habit, were the root causes of the practice in Fiji.

During the Fijian wars of the early nineteenth century, a portion of every captive was eaten.

Raids and surprise attacks were undertaken solely to procure human flesh for chiefs who had become addicted to cannibalism, Thomson said.

In Nadroga, the liver and the hands of an enemy were sometimes preserved by smoke in the house of slain relatives.

“Whenever regrets for the dead would wring his heart, the warrior would take down the bundle from the shelf over the fireplace, and cook and eat a portion of his enemy to assuage his grief,” Thomson said.

The relative continued to do this for one or two years until all was consumed.

“In the native mind, the poles of triumph and of humiliation are touched by the man who eats his enemy and the man who is about to be eaten.”

The highest act of vengeance was cooking the body, and leaving the flesh in the oven as if unfit for food.

The Rev. Joseph Waterhouse, the English-born Australian Methodist minister credited with having converted Seru Epenisa Cakobau, dug up one of these ovens while gardening at Bau.

Once, the bodies of the slain were set up in a sitting posture in the bow of the canoe.

While this happened, drums kept beating all the way across the sea, and as the warriors got near the village, a man kept striking the water with a long pole to announce their success.

The warriors danced the cibi on the deck.

“It was usual for the women to troop down to the water’s edge dancing a lascivious dance, and when the bodies were flung out, to cover them with nameless insults,” Thomson said.

“But in this instance (on the Vanua Levu coast near Mali) they were carried to the village square and set up in a row, with their war-paint still on them, while the whole population of the village sat down in a wide circle.”

An old man approached the bodies, and, taking a dead hand in his, began talking to them in a low tone.

Then he raised his voice and delivered the last sentences as loud as he could shout.

He kicked the bodies down. There were shouts of applause and laughter.

The spectators seized an arm or a leg of the deceased and dragged them off through the mud and over the stones to a temple.

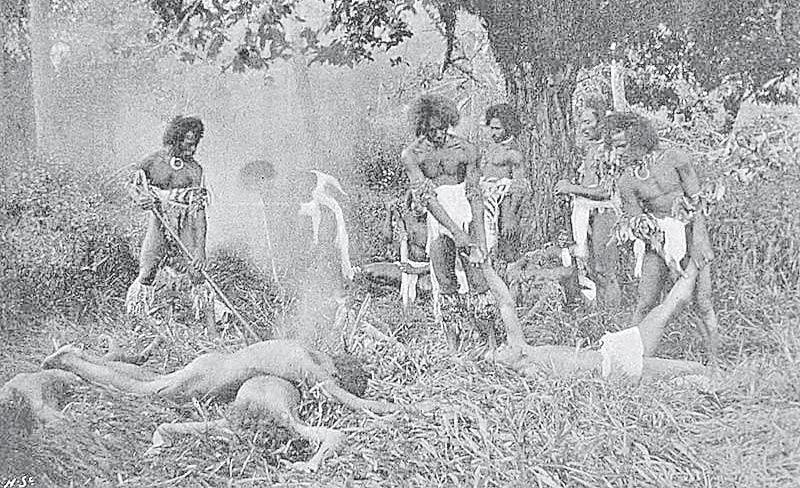

The girls danced while a butcher, armed with a stone axe, some shells and a number of split bamboos, got to work and put the bodies in a lovo.

The lovo was covered with soil until the morning.

“The cooked meat was then distributed with the ceremonies usual at feasts, and warriors from a distance, after tasting a small portion, wrapped up the remainder to take home as a proof of their prowess,” Thomson said

The cannibal fork

In old Fiji, sex and age could not be used to escape the cannibal oven.

Adult men and woman, as well as children, were eaten.

However, the flesh of young people between 16 and 20 years was regarded as the tastiest.

“The upper arm, the thigh and the heart were the greatest delicacies,” Thomson wrote.

“An ex-cannibal in Magomgondro (Magodro) told me that the upper arm of a boy and girl tasted better than any other meat.”

That same man had eaten part of the missionary Rev. Thomas Baker in 1867.

He said, “the flesh of white men was inferior to that of Fijians, and had a saltish taste”.

In the police expedition to Navosa in 1876, Dr William McGregor surprised a village and found a human leg, hot from the oven, laid out upon banana leaves.

The skin had parted, disclosing a layer of yellow fat.

It was said that when the flesh was kept for several days it emitted a phosphorescent light that could be used in the dark.

Then, the early Fijians had no emotions about killing, even the eating of innocent women and children.

Moku na katikati (club the women and children) was a principle some people used.

“They explain that, since the object of war is to inflict the maximum of injury upon the enemy, a twofold purpose is served by killing women—distress to their relations, and the destruction of those who might breed warriors to avenge them,” said Thomson.

The most celebrated cannibals on record were Tabakaucoro, Tanoa and Tuiveikoso of Bau, and Tuikilakila of Somosomo. But the reputation of these men paled beside that of Udreudre of Rakiraki in Ra.

His victims were called lewe ni bi (contents of the turtle trap).

He even has a cannibal fork named after himself.

History contends that Udreudre’s son once took a missionary to a line of stones, where he revealed that each represented a human being that was eaten by his father since middle-age.

They numbered eight hundred and seventy-two.

Some people believed he ate close to 1000 men.

The fork used exclusively for human flesh pointed clearly to the religious origin of the practice, according to Thomson.

The cannibal forks were never employed for other kinds of food, even food presented to the gods.

“There was some quality in human flesh that made it tabu to touch it with the fingers or the lips,” Thomson said.

The fork was “tabu” to everyone except its owner.

If it belonged to a high chief, it always had a special name.

“Persons slain in battle were not invariably eaten, for chiefs of high rank were often spared this indignity, and if a friend of the dead man happened to be of the victorious party he might intercede to save the body from the oven.”

In such cases, a peace truce was called. Relatives of the dead were allowed to come and remove the body for burial.

At the funeral, the mourners cut out their thumbnails and fixed them on a spear, which was preserved in the temple to remind them of the service done to them.

The abolition of cannibalism started following the widespread influence of Christianity.

As Fijians accepted another religion totally different from what they used to believe in, the act of eating human flesh died out among the indigenous population.

(This article was written based on Basil Thomson’s The Fijians – A Study of the Decay of Custom. Thomson was a former Fiji stipendiary magistrate and commissioner of native lands. He travelled extensively throughout Fiji.)

Editor’s note:

History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too.