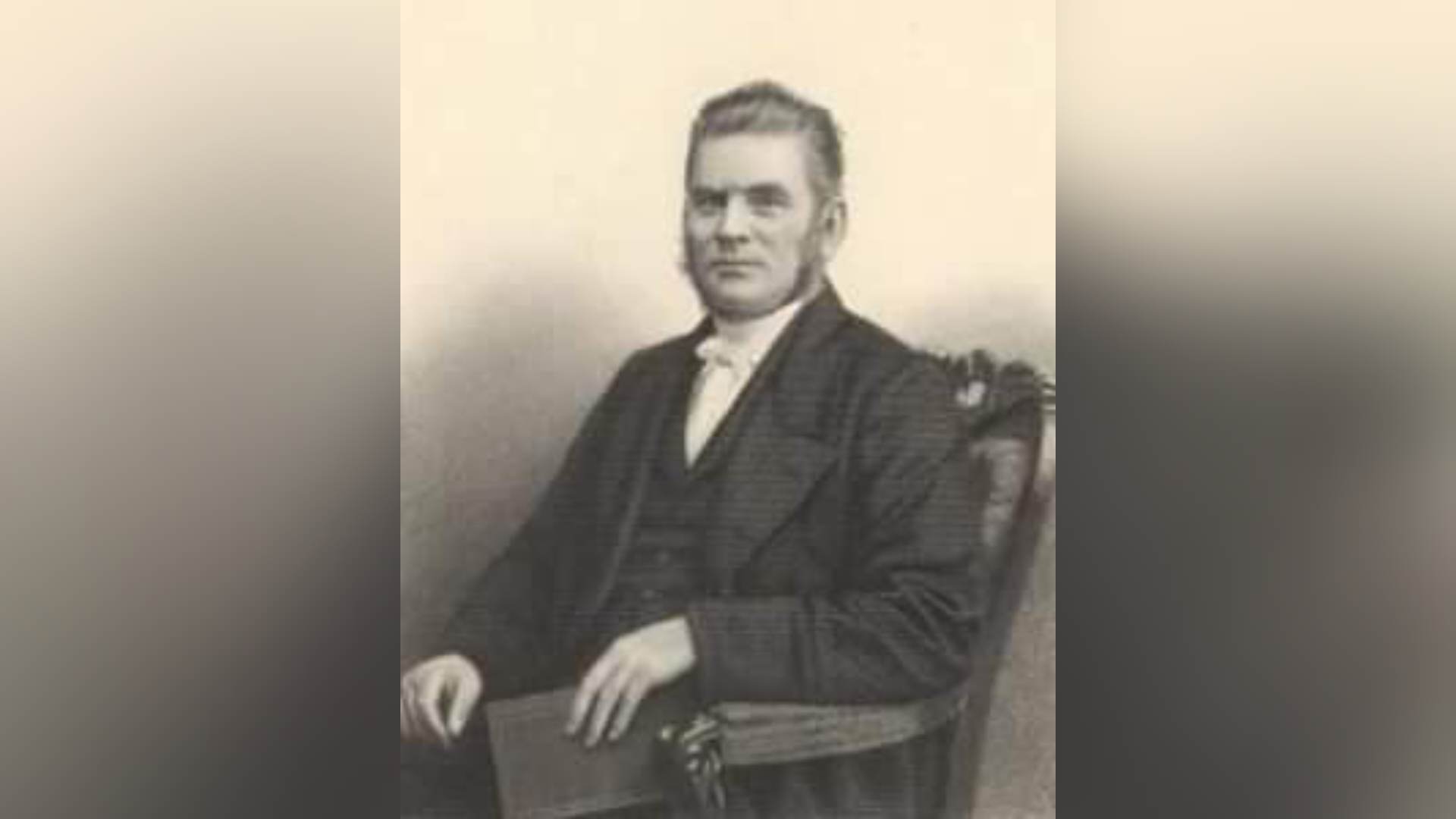

Wesleyan Methodist missionary, James Calvert who had spent 17 Wyears in Fiji in the 1800s experienced many encounters that challenged his work and perception of the Fijian people and serving God.

He later recognised that his life was no longer his own. While the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society was relatively new in 1838 as the new mission had begun three years before, his entry to the mission at Lakeba on December 22, 1838 was where his life work would begin.

His memoir, “James Calvert of Fiji’ written by G. Stringer Rowe published in 1893 has a wealth of information on his work at Lakeba, Ono and Viwa and the many struggles he faced with his wife Mary Fowler.

Lakeba and Ono (Lau)

When Calvert arrived on a Saturday afternoon, Reverend David Cargill, one of the two founding Wesleyan missions in Fiji, was unaware that three missionaries would be joining the mission.

“When the news reached him, Mr Cargill was shaving and in his eagerness suspended the operation and appeared half shaven to greet them,” Rowe wrote.

“On the next day, Sunday, the ladies disembarked, and the united mission band, in that house where prayer was wont to be made, joined in Divine worship.

“Then followed a busy week, getting ashore, and stowing away goods and stores and the printing press and all its belongings.”

Rowe stated that during their first few weeks at their residence, the missionaries had experienced a very peculiar life and an even fierce hurricane which caused damage to the houses of the mission.

Calvert and Cargill planned to obtain posts for rebuilding and asked a chief of high rank as he had some ready cut wood. They were met with a direct refusal as the posts were prepared for a temple and if he were to give them away, he feared that traditional gods would eat him.

It wasn’t until three months after his arrival that Calvert began to preach and his broken Fijian sounded stranger to those that heard him. That did not stop him from increasing his stock of words and phrases daily.

“Calvert had fully reckoned upon being employed in working the press. One of his colleagues, however, understood printing, and, after a good deal of deliberation, it was decided that the press should be set up at Rewa.”

In Sunday June 23, 1839, Calvert’s journal entry which was recorded in his memoir stated: “Preached in English in our home this evening. Our dear child was baptised today, her name is Mary. She is only three weeks old this evening.

About forty Fijians and Tongans were baptised at the same time. We held a lovefeast in the afternoon.” Four days later, he sailed to Namuka in a native canoe and did not arrive until the next day when he baptised 10 adults, six children and preached twice.

“The people are steady in their profession of Christianity but ignorant having spent their early days in heathenism. “On visiting the heathen chief who is the ambassador of this place to Lakeba, I found him lying on a mat very ill.

“I talked to him some time about Christianity. He said that it was very good and that he should become religious when the chief of Lakeba did.”

Revised mission plans caused Calvert to remain alone at Lakeba when he returned and it was cheerful news when 10 Christian Tongans with their wives and children arrived to help in the Fiji mission.

The rest of this first year of his mission life was spent in visiting the places on Lakeba and such outlying islands as he could reach.

On September 1839, Calvert wrote of receiving a letter from two teachers, John Havea and Isaac Ravuata who were stationed at Ono since February 1838.

The letter read: “The number of the men who worship God in Ono is 120, the women 113. We disclose to thee what we have received for books a great number of mats, a large quantity of yams, sinnet, and native cloth. We have heard of scarcity of food at Lakeba, and desire to bring the goods to thee.

“We beg of thee to send a canoe, and also a little ink. The good report has sprung up in this land, Ono. There are three houses of worship in Ono, one in Ono Levu, one in Matakana, and one in Ndoi.”

While Calvert was set to also learn the Tongan language he was busy preparing for the press to make copies of the New Testament which older missionaries had translated. In the earlier months of 1840, Calvert was in bad health due to the lack of proper food which caused him to become frustrated and depressed.

“I frequently suffer exceedingly in my mind for what appears to be idleness; but no sooner do I apply myself somewhat closely to study, or actively to bodily exertion, than I am upset one way or another,” his journal entry stated.

“I have a considerably increased desire to do good, and should rejoice to see the translation of the Bible completed.”

Calvert described his visit to Ono as heart refreshing and scary and how the inhabitants were notorious for bad conduct towards those that visited them but the changing grace of God renewed their characters.

During 1841, another child was born at the mission house and Calvert got exceedingly occupied with the press as the ‘first reading books and catechisms’ was increasing.

On April of 1842 he went to Oneata where the people had finished the construction of a large chapel where he conducted various marriages.

He account of his visit was: “In the afternoon I preached from Acts 33. The people were very attentive. Their singing is very bad, but I cannot help them, as I know only one tune.

“A canoe has gone to Lakeba to bring an Oneata chief to the opening of the chapel. I wrote to my dear wife, desiring her to come with the old chief, that she might see the chapel, and teach the people to sing.

Viwa

After a long ten years of work at Lakeba and its surrounding islands in 1948 there was an urgent need for Calvert’s immediate help on Viwa Island. This station was close to the dominant power Bau and was of great importance.

Rowe stated that the press had been installed nine years before on Viwa and the missionary who managed it had recently left, leaving it upon Calvert to manage. “He felt certain that he could not undertake it and do justice to the rapidly growing claims of the general mission work.

“He was cheerfully willing to give it the oversight of his skilled knowledge, but he could not enter upon the labour of the printing and binding.”

In another of Calvert’s journal entries, he wrote how help was wonderfully provided when their printer had failed when the new edition of the New Testament and other book were urgently required.

While a man from London was not found who would be content with small and hard work, a French Count who had been wrecked in Fiji wished to be employed and saved by the grace of God.

“I taught him printing and bookbinding, which he quickly learnt; and just then, when we were in deepest need, he became a most efficient labourer with us,” Calvert wrote.

“A new edition of the New Testament and all the books we required were well done, and quickly supplied, helping on the work amazingly.”

As mentioned in the first article on Calvert last week, his most interesting and instrumental experience was his close relation to Cakobau which later led to his conversion to Christianity.

• Next Week: PART 3