Last week, we began discussing how orientation towards life in general and education in particular has changed over time. We attributed this to what appears to be generational changes in values, attitudes, priorities, etc. in peoples’ orientation towards life. Thus, we analysed to some extent the baby boomer generation’s orientation towards life and how it was shaped through their upbringing. It needs to be pointed out that researchers have pegged this generation as those born between 1946 and 1964.

We said that theirs was a beginning of destruction, utter deprivation, drudgery and extreme struggle for survival. Those shared hardships forged enduring bonds among the family, community and later, larger socio-political units that worked together to grind out an existence amid unbearable and insurmountable hardships at the time. This is why a key feature among this generation is seen in the fact that they tend to value relationships and prioritise spending time with family and friends.

Some of you wrote to me seeking further information and clarifications on the parallels I tried to draw between the struggles and hardships endured after 1945 around the world and the trials and tribulations of the Girmitiya wherever they were based in the world and, in particular, here in Fiji. Let’s start by briefly looking at the struggles of the Girmitiya and how it shaped their orientation towards life and education.

Girmitiya offspring

THE Girmitiya were a generation who were shipped to Fiji (and other parts of the world) from India to work primarily in plantations in order to make those British colonies economically viable. Between 1879 and 1916, some 56,000 Girmitiya had arrived in Fiji amid ever-increasing demands for more labourers. The highly exploitative recruitment practice only stopped after the atrocities perpetrated on the Girmitiya were finally acknowledged by more receptive and concerned colonial officials after irrefutable reports began to surface from different sources.

I will not delve into the injustices, toil, tears and hardships of the Girmitiya here. What I will focus on is the lives of their offspring and the generation that coincided with the baby boomers. Girmit came to a grinding halt in 1921, five years after it was abolished in 1916. That was 42 years after the first Girmitiya stepped off the Leonidas in May 1879. Once freed of the yoke of “slavery”, those first generation Girmitiya began to carve out a living as either contracted cane farmers, free labourers or/and artisans.

Life had not changed much for them apart from the fact that they were now no longer bound by the pernicious contractual constraints of Girmit. The socio-political and economic environment that they operated in was unhelpful at best and hostile at worst for them. The Colonial Sugar Refinery Company (CSR) constantly cheated and short-changed them in their cane dealings. The little businesses that sprouted through later arrivals from India opened lines of credit at rates that gouged at their livelihoods. Access to legal assistance was virtually non-existent.

This stoked a passionate flame of focused resentment and simmering anger that led to a sustained undertaking to set up schools and agitate for political representation. The next generation of Indians that followed the Girmitiya – the first-generation offspring of the Girmitiya – were the ones that took up the baton and ran through the next phase of the struggle. It was this generation that mirrored the hardships, deprivations and travails of the baby boomers. Among these were some of the best professionals that the country has produced. We will get back to this later, but let’s analyse the baby boomers further here as the two are linked.

After 1945

Followers of history will know that it was this generation, the baby boomers, that went on to play a key role in the reconstruction efforts that followed World War II. Europe, Japan, South-East Asia and parts of the Pacific were the hardest hit and much work was needed there. I mentioned US funding as a key cog in the reconstruction efforts. In addition to this, local labour and leadership galvanised projects as people attempted to shrug off the destruction, despair and despondence that the unwelcome and unwanted war had left in its wake.

India features large in the immediate post war era for a number of reasons. It had been struggling for independence from Britain for a long time. The struggle had been long, bitter, bloody, stubborn, but unquelled when Britain took up the cudgels to push back against Nazi Germany in 1939. Many in India were loathe to join the British war effort, but leaders like Gandhi saw it as a need and a patriotic undertaking. In the end, over 87,000 Indian troops, and 3 million civilians died in World War II.

The chapter involving the Indian National Army, set up in a POW camp in Singapore in 1942, makes for another narration. What is important here is that they were primarily focused on using the opportunity presented by the war to force Britain to release India through armed struggle. This did happen in 1947, two years after the war ended, but not in the manner that they had envisaged. The story about the partition of India, independence and its aftermath makes for huge lessons in a number of spheres.

For this article, it needs to be noted that India’s independence sparked off what was to become a scramble for independence all over the world. Let’s get back to post-war reconstruction and its effects on the baby boomer generation.

Reconstruction, independence and beyond

As major capital projects like wharves, bridges, highways, airports, hospitals, etc., began to spring up, in former colonies a new desire for independence and self-determination began to enter national discourse. The type of focused work ethic developed in the reconstruction efforts now evolved further as people began to focus on their own destinies albeit within the aid-trade-investment folds of their former masters.

The baby boomers and their parents were at the forefront of the immediate reconstruction efforts that followed WWII. They were again in the forefront of negotiations and struggles for independence from the colonial powers who they had supported and fought for during the war.

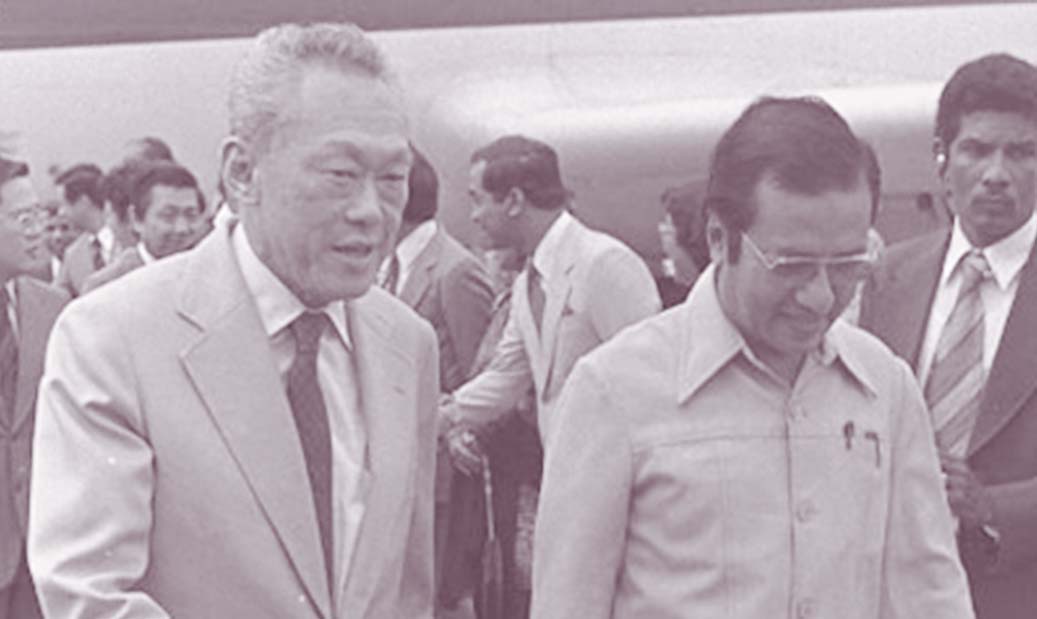

Leaders like Julius Nyerere (Tanzania), Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Kenneth Kaunda (Zambia), Seretse Khama (Botswana), Robert Mugabe (Zimbabwe), Nelson Mandela (RSA), Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya), Patrice Lumumba (Congo), Gandhi-Nehru-Patel (India), Ratu Mara (Fiji), Michael Somare (PNG), Peter Kenilorea (Solomons), Walter Lini (Vanuatu), Lee Kwan yew (Singapore), Sukarno (Indonesia), Ho Chi Minh (Vietnam), Aung San (Burma), etc. were all involved with or were in the boomer generation.

The researches on generational characteristics cited earlier highlighted that the baby boomers are goal centric and motivated to work hard to achieve their dreams. It was the deprived beginnings – the search for hope amid utter despair and devastation, the inevitable sacrifices and self-deprivations, the dogged perseverance despite the uncertainty of results and rewards, and the unceasing effort for a yet unclear future – that inculcated the work ethic and motivation to persevere at all costs that marks the baby boomers as a generation apart.

I will round off this analysis of that generation with a run through three other traits identified by the researches cited here. Till then, enjoy the rugby – Deans, PNC, RC.

Remember that 60-0 drubbing of Pat Lam’s Samoa at the National Stadium in 1996? Will Nasinu Secondary School finally etch its name on the Deans Trophy and will Queen Victoria School allow this? How about Niusawa Methodist taking the U16 Raluve? Sa moce toka mada.

- DR SUBHASH APPANNA is a senior USP academic who has been writing regularly on issues of historical and national significance. The views expressed here are his alone and not necessarily shared by this newspaper or his employers. subhash.appana@usp.ac.fj