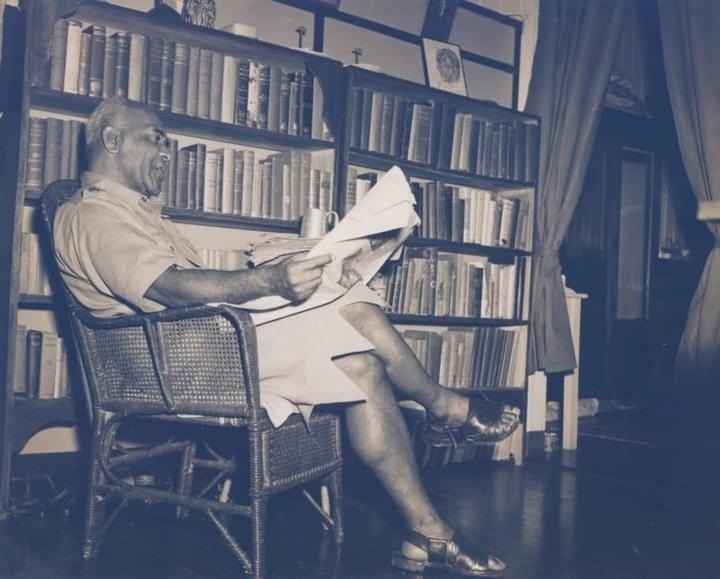

As an individual person, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna distinguished himself in many different ways. He was born on April 22, 1888 into high chiefly status and privilege. In his education, he was the first iTaukei to qualify as a university graduate. His studies at the University of Oxford and at the Middle Temple in London earned him a BA and LLB degrees. During World War I, he joined the French Foreign Legion and was awarded by the French Republic its highest military award for gallantry. In the British colonial administration, Ratu Sukuna was the first local officer to attain the highest rank of Administrative Officer Class 1 and to be appointed to serve as Secretary for Fijian Affairs. And he was knighted twice by the British Monarch for his distinguished public service in the colonial administration. As the ultimate recognition of his high qualities of leadership, he was appointed as Speaker of the colony’s Legislative Council in 1954 and he served in this capacity until his death on May 30, 1958. For the iTaukei, Ratu Sukuna continues to be highly revered today for his sterling work in the survey and demarcation of the boundaries of mataqali-owned native land throughout Fiji.

However, notwithstanding all these individual accomplishments, what in my view has earned Ratu Sukuna our esteem and respect as a great leader and statesman was his outstanding contribution to the reform of management of all iTaukei customary-owned land in order to enable its productive use for the benefit of both the landowners and tenants, and of Fiji as a whole. Ratu Sukuna was entrusted by the colonial administration to consult the iTaukei through their Great Council of Chiefs and fourteen provincial councils, and to secure their support for this native land management reform through the draft Native Land Trust Ordinance, which the British colonial government brought before the Legislative Council in 1940.

The Native Land Trust Ordinance

The Native Land Trust Ordinance was enacted by the Legislative Council in February 1940 with the full support and endorsement of the Great Council of Chiefs and the 14 provincial councils, acting on behalf of all indigenous Fijian customary land and resource owners. Its fundamental purpose was to establish a clear, streamlined and integrated administrative system for the management of native land. Legal ownership and control of all native land would henceforth be vested in a board of trustees, the Native Land Trust Board, presided over personally by the Governor, the resident head of the British colonial administration in Fiji. All native land is to be administered by the board for the benefit of the native owners. The board has power to set aside and proclaim native reserves; that is, areas of native land for the exclusive use of all iTaukei. These areas would be demarcated and kept for re-allocation in the event a mataqali, for some reasons, needed additional land for its members. But the board was also conferred with full powers to grant to any Fiji citizen in need of land, under certain conditions, leases or licenses over native land not included in the native reserves.

The native owners would benefit from the lease rent or license fee income; the tenants would secure land for their farms, their houses, and their businesses; and Fiji as a whole would gain from the increased economic activities and the social security provided.

Social changes and increased demand for land

As background to the imperative need to reform the management of native land, the years onward from the 1920s were a period of rapid social, economic and political changes that confronted and challenged the British colonial administration. To begin with, there was a dramatic change in Fiji’s population dynamics. In the population census of 1881, it was recorded that the iTaukei numbered 114,748 or 90 per cent of Fiji’s total population of 127,486. There were only 588 Indo-Fijians, or 0.5 per cent of the total population. By the population census of 1936, Fiji’s total population had increased to 198,379. However, the iTaukei population had declined to 97,651 or 49.2 per cent. The measles epidemic had decimated the iTaukei population and was responsible for the continuous fall in iTaukei numbers from an estimated 200,000 in 1860. In stark contrast, by 1936, in only 55 years, the Indo-Fijian population had increased from the 588 or 0.5 per cent recorded in 1881 to 85,003 or 42.8. The indenture system from 1879 to 1916 brought to Fiji more than 60,000 people from India to work in the sugar plantations. The majority of these indentured workers opted to remain in Fiji at the end of their indenture. It was this that led to the substantive increase in demands for access to native land for agricultural use and settlement. In addition, free settlers from Punjab and Gujarat began to arrive in Fiji in the 1920s. Unfortunately, the administrative system for the leasing of native land was extremely complicated and cumbersome. The aspirant lessee had to apply to the Commissioner of Lands in Suva or the nearest Commissioner of Division in the British colonial administration. The commissioner would notify the Buli, who in turn consulted the Tikina Council at which the landowners expressed their views about the proposed lease. The Buli would then inform the Commissioner of the Tikina Council’s decision. The application and the recommendations would be considered jointly by the Commissioner for Lands and the Secretary of Native Affairs, and if they approved, the lease was then sold at a public auction to the highest bidder. One could imagine the many underhand dealings to influence the outcome of these land auctions.

The vision and achievements of Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna

It was against this background and environment that Ratu Sukuna convened a meeting of the Great Council of Chiefs in 1936 and very tactfully told the gathered chiefs: “We cannot in these days adopt an attitude that will conflict with the welfare of those who like ourselves live peacefully and increase the wealth of the colony. We are doing our part here and so are they. We want to live; they do the same. You should realise that money causes a close inter-relation of interests. If other communities are poor, we too remain poor. If they prosper, we also prosper. But if we obstruct other people without reason from using our lands, following the laggards there will be no prosperity. Strife will overtake us, and before we realise the position, we shall be faced with a situation beyond our control, and certainly not to our liking…You must remember that Fiji today is not what it used to be. We are not the sole inhabitants; there are now Indians and Europeans”. (Deryck Scarr, Ratu Sukuna, man of two worlds, 1983) Ratu Sukuna made this statement four years before his Native Land Trust Board Bill was presented in the Legislative Council. The proposed legislation, drafted in 1937, encapsulated his vision of what he thought would be the best arrangements for native Fijians and for Fiji as a whole. And he allowed enough time in order to build up support for his new native land management policies among the chiefs and the indigenous Fijian community as a whole. Today, as we reflect on Ratu Sukuna’s pioneering contribution to native land management reform, we can say that his greatness as a leader and statesman is that his vision as he articulated then, remains true today as the foundation of public policy on native land. To begin with, Ratu Sukuna recognised that Fiji had become a multi-ethnic society and this sociological fact could no longer be ignored. Native lands are to be managed for the benefit of the customary owners, the tenants, and the entire country alike. As he reminded members of the GCC in 1936: “If other communities are poor, we, too, will remain poor. If they prosper, we also prosper.” Ratu Sukuna envisioned the new management regime in the Native Land Trust Ordinance as the best way to safeguard the proprietary interests of the iTaukei landowners while opening up native land surplus to the maintenance needs of its customary owners to any citizen of Fiji who needed land for their livelihood. And one final point. His leadership approach in assiduously taking meticulous care to consult the Great Council of Chiefs and the provincial councils, and to secure their support for the new management regime for native land, as contained in the Native Land Trust Ordinance, is an outstanding example of what our elected political leaders in Government and in Parliament ought to be doing collectively and regularly with all iTaukei land and resource owners. It is national leadership by building consensus among the various interested and directly affected stakeholders in the wider community. It is leadership that sets a vision which embraces and benefits all.