1 Corinthians 9:22 reads: I have become all things to all people, so that by all possible means I might save some.”

This Bible verse describes the adaptability of the prophet St Paul in environments that he may not be familiar with.

Ultimately, the sacrifices we make and the things we learn help us serve our purpose better.

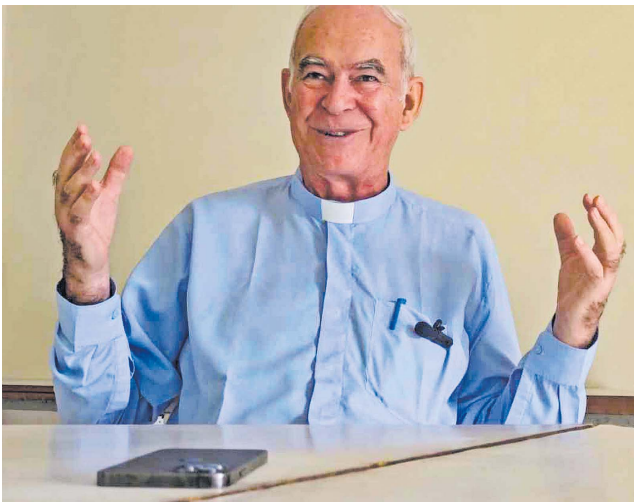

In a recent conversation with The Fiji Times, Columban missionary Father Frank Hoare shared memories of his early years in Fiji, a land he came to call home after arriving in 1973 as a young priest from Ireland.

At just 26 years old, Father Hoare stepped off the plane into Suva’s thick tropical heat and torrential rains, conditions he would later describe as a stark contrast to the “cold grey days with gentle showers” of his homeland.

It was November, the beginning of the wet season, and the start of what would become a lifelong mission among the people of the Pacific.

Assigned to the Columban Centre House in Tamavua, which also served as the presbytery for St Joseph the Worker Parish, the newly arrived missionary immersed himself in language studies.

Unlike many others, he was asked to learn Hindi first.

“It was thought to be more difficult than the standard Fijian language and it was the language of the Indo-Fijian people, who were predominantly Hindu and Muslim in religion,” Fr Hoare recalled.

“I had four hours of class every morning in the Archdiocesan offices in the centre of Suva with a young Indo-Fijian lady teacher and I had the use of language tapes and books from a language school in India.

“All that was needed was the will and the effort.”

The dedication was clear: he wanted to communicate not just with Christians, but with non-Christians as well, those who might never otherwise hear the message he carried.

“My very first day of learning Hindi, when I arrived, I was asked to learn Hindi first because as a missionary we wanted to reach out to non-Christians, but also it’s slightly more difficult than Fijian to learn.”

One of his first experiences in Suva left a lasting impression.

Walking through the city toward his lessons, he encountered a PWD worker with a “tekiteki (a flower, typically a hibiscus or frangipani, that is worn behind the ear), a lovely smile on his face and a cigar in his mouth.”

The moment struck him as something completely new.

“Wow,” he thought, “we don’t have PWD workers like this in Ireland”.

But language came with its challenges.

What he studied, standard Hindi, differed greatly from the Fiji Hindi spoken in homes and communities.

“The grammar is quite different and even some of the words are different.

“Even now, I speak Hindi, but it’s kind of a mixture of both.”

Despite the hurdles, he pressed on.

He fondly remembers practising with Indian families in Tamavua who welcomed him into their homes despite his early struggles with the language.

There were humorous moments too, like the time he tried to buy a shirt and asked for a “kameez, only to be met with confusion until he switched to “shirt”.

After a year of Hindi, Fr Hoare was sent to Labasa, where he lived and worked in an Indian settlement for two years.

Immersion deepened his understanding of the culture and language, forming a foundation for the decades of ministry that would follow.

Later, he would return to Suva for six months to learn the i-Taukei language and traditions under the guidance of a matanivanua from Bau.

“He taught us much of the culture and rituals that go with it.

“That was a really wonderful time.”

His first Easter Vigil in Fiji remains a vivid memory.

At a small chapel in Tamavua run by the Sisters of Compassion, he was expected to sing the Exsultet, a lengthy and ornate hymn to the risen Christ.

Nervous about getting it right, he chose to recite it instead.

“After the service, the community leader said to me, ‘We’re surprised you didn’t sing the Exsultet. Father Reluctant, who was here before, used to practice it all day and then sing it. But he couldn’t sing it.’”

The following day, on Easter Sunday, Fr Hoare was invited to a lovo celebration in Wailoku.

The steep descent to the house marked more than just a physical journey, it was another cultural moment that reminded him he was far from Ireland.

As he followed another priest, Father Ed Quinn, down the path, he overheard two women behind him say: “If Father Quinn wasn’t a priest, I’d go for him.”

He laughed at the memory, noting, “It’s a very human thing”.

Despite the warmth of his Fijian home, Ireland was never forgotten.

He recalled returning for the first time after four and a half years in Fiji.

“The excitement of touching down again in Dublin, expecting to see the family again, that was terrific.”

His parents welcomed him with love expressed in small but meaningful ways: his mother knitting him a sweater for the Irish weather; his father stepping away from the dinner table to pick fresh strawberries from the garden for his dessert.

“I said, wow, this is love. This is real love.”

Even back home, his missionary spirit persisted.

Fluent in Irish, he volunteered to preach on the Aran Islands about his experiences in Fiji.

On Inishmaan, the middle island, he shared stories of Fijian customs and the symbolic value of the “tabua”, or whale’s tooth.

After Mass, a local man offered him a whale’s tooth as a gift, an object that had washed ashore from a dead whale and been salvaged by the islanders.

“So I’m one of the few people, I think, that have brought into Fiji instead of taking out of Fiji.”

Father Frank Hoare’s early years in Fiji were marked by cultural immersion, linguistic challenges, and spiritual commitment.

His story reflects the journey of a man who sought not only to teach and serve but to understand and belong.

n In next week’s edition, we will journey further into the adventures of Fr Hoare and his life among the people of Fiji.