Last week, we highlighted discrepancies in the amount of weapons that actually arrived in Fiji and the amount that was seized by security forces. We said that, depending on what we considered accurate, some three tons of arms were never recovered. More than 45 people were arrested on suspicion of being part of the deadly conspiracy. Many were released after initial “interviews” until 21 were actually charged and presented in court. We ended by saying that for some intriguing reason these “enemies of the state” were also released after some time. It was obvious that something was happening behind the scenes. However, before we get to the actual power struggle going on behind the scenes following the 1987 coup, let’s look at a few other developments that should help us understand that vei dre better when we actually start zooming onto it later in this series. Let’s focus first on how armed soldiers arrived in Rotuma in the aftermath of May 1987.

The Rotuma sedition case

ROTUMA lies about 600 kilometres north of Viti Levu. It is populated by a people of Polynesian origin whose roots are sometimes speculatively traced to the Rapa Nui of Easter Island.

Readers should note the use of the word “speculatively” here. Rotuma was not included in the annexation of Fiji in 1874 because of some administrative oversight in the paperwork.

In July 1879, the island’s chiefs sent a letter to Queen Victoria asking to be annexed. This was accepted without too much fuss, but there was one concern that the Crown had — the island was remote and small. It would be very difficult to manage.

In other words, they were faced with a problem that they would encounter a few years later in the case of Gilbert Islands and Ellice Islands. Anyway, they decided to include Rotuma in the Fijian colonial apparatus set up in Levuka for running Fiji. That’s how Viti kei Rotuma was born. That’s why Rotuma is included in Fiji as a separate entity. The setup was designed for colonial administrative convenience. The same was to follow in 1892 when the Gilbert Islands, Ellice Islands plus the northern Line Islands, and the Phoenix Islands were lumped together as one administrative entity called Gilbert and Ellice Islands.

Coming back to Rotuma, the bulk of Rotumans live and work in Fiji while the island remains largely agrarian; oranges (slowly returning), coconuts, root crops and sea foods are its main outputs. Interestingly, Rotumans have held a disproportionately large number of key positions in the Fiji civil service over the years. Major General Jioji Konrote, apart from playing a key role in Rabuka’s post-coup cabinet of 1987, had a colourful military career rising to the rank of United Nations Assistant Secretary-General and Force Commander UNIFIL in Lebanon. He hit the pinnacle of his career when he served as the President of Fiji from 2015 to 2021.

Another prominent Rotuman was Visanti Makrava who took over the National Bank of Fiji on October 2 1987 at Rabuka’s behest. It was under his stewardship that the NBF bellied up amid losses of up to $250-300 million. In July 1995, when this colossal banking debacle hit the frontlines, PM Rabuka told the Review Magazine, “when he (Makrava) was made NBF chief, not even the NBF board nor the Minister of Finance knew. And see the influence this man has made on the bank; I was assured that I had made the right choice”.

Makrava was obviously not considered responsible for the collapse of the NBF. We will return to this case later.

On the political front, Rotuma has largely been left to manage its own affairs even though a government administrator is stationed there. What is of importance to us is that Rotuma has seven tribes. One of these tribes, the Molmahao, had tended to operate slightly differently from the rest.

It was the Molmahao who raised the Union Jack in 1988 in defiance of the coup regime in Suva to show their preference for the British Crown.

Their clan leader, Gagaj Sau Lagfatmaro, had inspired this defiance from his residence in Auckland and the number two man in the Fijian military at the time, Colonel Jioji Konrote hated him for this.

He was reported to have yelled in his office at Delainabua, “if Gibson ever comes back to Fiji, I will personally execute him” (Harder 1988, p.30).

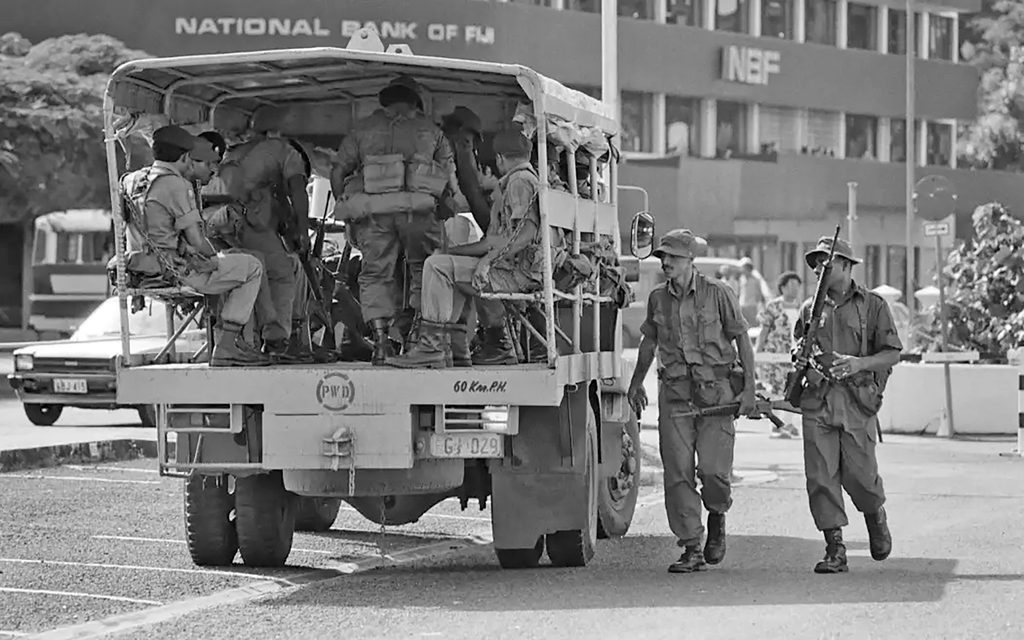

Following the raising of the British Union Jack on Rotuma, there was swift reaction from the coup regime in Suva.

A group of armed soldiers were swiftly dispatched to the island. And in a show of who was in power, the government administrator on the island took a .38 pistol and fired at the frail and forlorn-looking Union Jack that had been hoisted by the Molmahao. Shortly afterwards, eight Molmahao clan chiefs were charged with sedition and detained.

The alarm, however, was far from over as the soldiers stayed back ostensibly to control pigs who had become a pest and destroyed farm produce. Their real reason for remaining there was more ominous.

At the end of the initial trial in Rotuma where jurisdictional issues were deliberated on, seven of these secessionists were shipped off and remanded in custody in Suva. The eighth was freed on the basis of his age.

Amnesty for guns

The remaining seven were released later as part of a 30-day amnesty that appeared to also cover the gunrunners of Lautoka. I say “appeared to” because on the ground nobody seemed to be sure whether the 21 men detained for the Guns of Lautoka were covered by the guns amnesty. Some military officers like Major Mataitini were almost certain that the detainees were not covered because this would mean Rafik Kahan, the kingpin, would also need to be left out of the wanted list.

There was little doubt in anyone’s mind that Kahan would be extradited from London, and he would face the full brunt of the wrath of the seething Colonel Rabuka and the men in green at Delainabua.

To this end Captain Isikeli Mataitoga and Superintendent Govind Raju had already been despatched to London to push for extradition of the now notorious criminal who was lounging in Brixton Jail after being arrested on July 22 1988.

On the other hand, Rabuka had already announced that the 21 detained men were covered by the amnesty and that anyone having any knowledge about the guns or wanting to hand them over would not be charged.

His advisers felt that Kahan could be dealt with outside the ambit of the amnesty. After doing a few back-flips Rabuka stuck to this and the 21 were released with interesting stories to share about their harrowing sojourn as guests of the coup regime.

When their lawyer, Christopher Harder, visited them at Natabua jail, there was clear evidence of torture and beatings on them.

This brings us to another point that we had raised earlier — that there was an intense power struggle going on behind the scenes.

The fact that the Rotuma chiefs were let off after being seen as traitors; the fact that the 21 gunrunners were let off after being detained as enemies of the State; the fact that Rabuka kept back flipping in his public pronouncements. All these point to unseen shifts in political support.

Just what was happening behind the scenes?

In order to understand this, we will need to go back to the lead-up to the 1987 coup and focus on who was involved. Until next week, have a fruitful break.

Former President Jioji Konrote at Borron House in Suva on August 31, 2018. Picture: JONACANI LALAKOBAU/FILE