Laurel Hubbard – the first openly transgender athlete selected for the Olympic Games – guards her privacy zealously, but has always insisted all she wants is to be herself.

Yet, the 43-year-old has been a polarising figure since she burst onto the world weightlifting stage in 2017 after transitioning to female.

The debate Hubbard has lived with for the last four years is likely to remain intense, after she was named in a five-strong New Zealand weightlifting team for next month’s Olympic Games in Tokyo.

All eyes will be on her as she strives for a medal in the +87kg women’s division.

Hubbard skipped a New Zealand weightlifting call in Auckland on Tuesday, and has thus far restricted her response to her selection to a New Zealand Olympic Committee (NZOC) statement.

She said she was “grateful and humbled by the kindness and support that has been given to me by so many New Zealanders”.

Hubbard was selected after meeting International Weighlifting Federation (IWF), International Olympic Committee (IOC) and NZOC eligibility criteria.

But NZOC secretary-general Kereyn Smith has admitted Hubbard’s selection will “divide people”.

Already, former New Zealand Olympic weightlifter Tracey Lambrechs has said she believes it’s unfair for Hubbard to compete in a women’s category and, if she wins, two gold medals should be awarded.

There have been conflicting studies around whether transgender women still retain significant advantages in power and strength when testosterone is reduced.

But debate is something Hubbard has become accustomed to since returning to weightlifting around five years ago.

Background

The Auckland lifter was born as Gavin Hubbard in February 1978. Hubbard’s father, Dick Hubbard, a cereal company magnate, was Auckland’s mayor from 2004 to 2008.

Gavin Hubbard set a national junior record with a 300kg total in the junior +105kg class in 1998.

While an impressive effort for a 20-year-old, it was not enough to make Hubbard a serious contender for a national senior team.

Hubbard has since said she took up “an archetypally male” sport such as weightlifting in a bid to feel more masculine. “I thought perhaps if I tried something that was so masculine perhaps that’s what I’d become,” she told RNZ’s Checkpoint presenter John Campbell in 2017. “But sadly, that wasn’t the case.”

In the same interview, she was at pains to dispel “one of the misconceptions that’s out there” that she had trained all her life and her transition had happened “relatively late in the piece”.

“What people don’t realise is I actually stopped lifting in 2001 when I was 23 because it just became too much to bear … just the pressure of trying to fit into a world that perhaps wasn’t really set up for people like myself”.

After living as a man for 35 years, Hubbard began transitioning to female through hormonal treatment around 2012.

By then, the rules around transgender athletes competing in sport had changed.

The IOC had moved through its Stockholm Consensus in 2003 to allow transgender athletes to compete in international events, and the IWF soon followed suit.

Now, under current IOC guidelines, issued in November 2015, athletes who identify as female can compete in the women’s category provided their total testosterone level in serum is kept below 10 nanomoles per litre for at least 12 months, and cannot change to compete.

Comeback

In 2017, Hubbard burst into national prominence – some 16 years after her last competitive clean-and-jerk.

She set an Oceania record of 113kg competing as a woman at the 2017 North Island Games, and also won the gold medal at the Australian championships.

The Kiwi – then aged 39 – lifted 123kg in the snatch discipline and 145kg in the clean and jerk for a 268kg total – 19kg more than her nearest rival, but still significantly below the 300kg New Zealand junior male record set as Gavin Hubbard in 1998.

Hubbard’s victory in Melbourne met with a storm of criticism from Samoan silver medallist Iuniarra Sipaia, who told The Samoa Observer Hubbard may have transitioned to female, but “it only changed the physical side … her emotions, her strength and everything is still a male. So I felt that it was unfair because we all know a woman’s strength is nowhere near a male’s strength no matter how hard we train.”

Hubbard qualified for the 2017 world championships in California, with the IOC ruling she had undergone at least one year of hormone therapy and was recording sufficiently low levels of testosterone.

She created international headlines when she got two silver medals in the +90kg division becoming the first New Zealand lifter – male or female – to make a world championship podium.

However, Tim Swords, coach of gold medallist Sarah Robles, claimed the American was congratulated by multiple coaches because “nobody wanted [Hubbard] to win”.

Hubbard refused to strike back at Swords, but insisted on her return to New Zealand that Robles had treated her warmly before the Anaheim event. “She gave me a hug, wished me luck and I believe she really meant it too.”

“All you can do is focus on the task at hand and if you keep doing that it will get you through,” she told Stuff in December 2017.

“I’m mindful I won’t be supported by everyone, but I hope that people can keep an open mind and perhaps look at my performance in a broader context.”

Hubbard referenced the rule changes made by the IOC in 2003. “Those are the rules under which I’m competing, so this isn’t a new thing,” she said.

Asked by Stuff if she saw herself as a role model, Hubbard said; “All I can do is be myself, do what I do and if people find inspiration then that’s great, but it’s not what I’m setting out to do.”

Temporary retirement

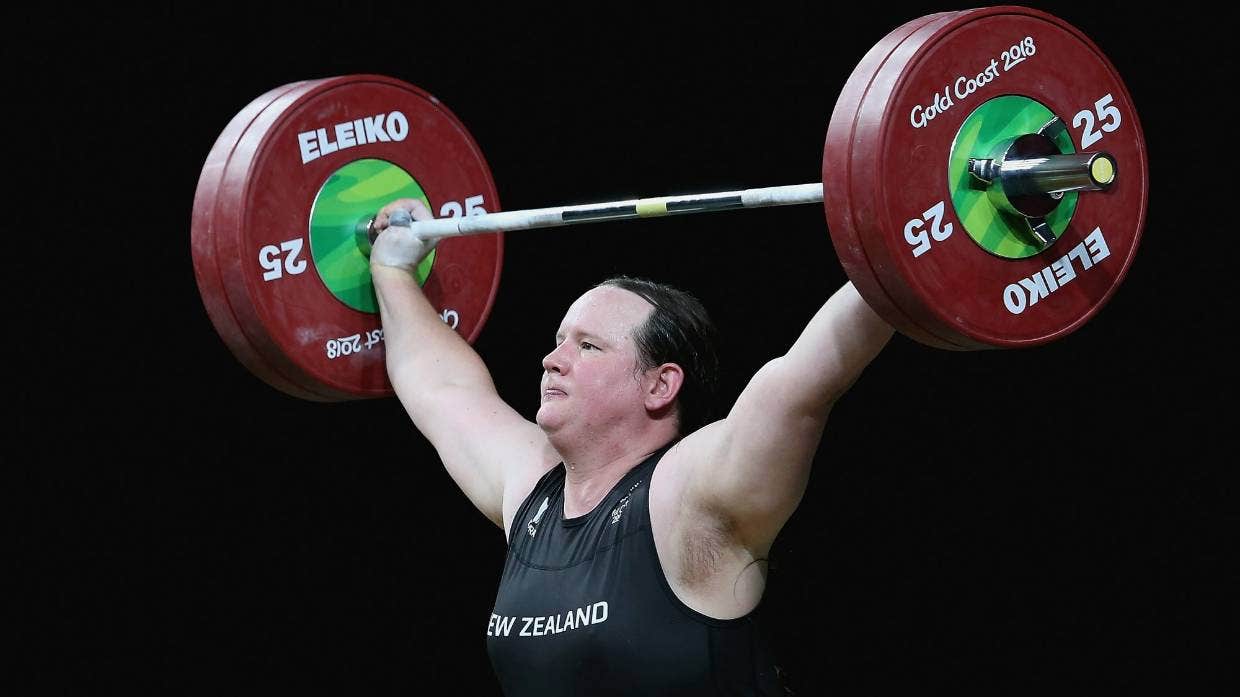

Hubbard’s world championships medals raised an expectation that she would win gold at the 2018 Commonwealth Games, but she was the centre of controversy before she even got to the Gold Coast.

New Zealand’s Human Rights Commission (HRCNZ) ruled that Hubbard’s selection and participation was legitimate.

Auckland University sports sociology professor Toni Bruce defended Hubbard’s selection, telling Stuff: “There has been some discussion that Laurel has psychological advantage because she previously competed in weightlifting as a man.

“What these comments don’t take into account is that her body has changed in many ways through the process of transitioning.”

That didn’t wash, however, with Australian Weightlifting Federation chief executive Mike Keelan, who claimed Hubbard would not be “on a level playing field”.

“We’re in a power sport which is normally related to masculine tendencies… where you’ve got that aggression, you’ve got the right hormones, then you can lift bigger weights,” he said. “If you’ve been a male and you’ve lifted certain weights and then you suddenly transition to a female, then psychologically you know you’ve lifted those weights before”.

Hubbard entered the Gold Coast Games as the red-hot favourite in the -91kg class, but she was forced out when she damaged her left elbow attempting a Commonwealth record 132kg in the snatch. As the bar fell behind her, Hubbard reeled in pain, clutching her elbow.

To the evident surprise of New Zealand’s weightlifting coaches, she said at a NZOC function for family and friends that she was going to retire because “my arm is busted”.

However, after treatment back in New Zealand for her ruptured ligaments, Hubbard had a change of heart.

By September 2018, she was fit enough to lift at the New Zealand championships.

Hubbard was back in the headlines in 2019 after revelations that she had pleaded guilty to a careless driving causing injury charge after her vehicle fishtailed on a sharp bend near Queenstown on October 24, 2018.

Her car hit a vehicle carrying an Australian couple in their 60s. The male driver spent nearly two weeks in Dunedin Hospital and needed major spinal surgery on returning to Australia.

Hubbard pleaded guilty in January 2019 and offered to pay the couple about $13,000, including $1000 for emotional harm.

The case could not be reported initially because Hubbard, represented by lawyer Fiona Guy Kidd QC, successfully applied for suppression orders at each of the five stages of the court process. The High Court in Invercargill overturned the suppression orders in July 2019 after an appeal by Stuff.

At Hubbard’s initial sentencing, Judge Bernadette Farnan discharged Hubbard without conviction noting she was a first offender, the low level nature of the accident, Hubbard’s remorse and the reparation payment. She disqualified her from driving for a month (the normal disqualification is six months) and ordered her to pay about $13,000 to the Australian couple.

In a rare move, the judge also suppressed Hubbard’s name until September 30, so Hubbard could train for qualifying events for the Olympics without the distress caused by social media comments responding to publicity about the charge.

The suppression order was later overturned by the High Court.

A day after her case was reported, Hubbard won the 2019 Pacific Games gold medal in Apia with a total lift of 268kg in the women’s +87kg category.

Her overall Apia haul included two gold medals and a silver, but Samoa Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi planned to appeal to the Pacific Games Council to address concerns around the eligibility of transgender athletes.

“This fa’afafine or man should have never been allowed by the Pacific Games Council president to lift with the women. I was shocked when I first heard about it,” he told the Samoa Observer.

“No matter how we look at it, he’s a man [sic] and it’s shocking this was allowed in the first place.”

Tokyo chance

Irrespective of the controversy, Hubbard’s efforts in Apia showed she was back at the level she’d displayed before her elbow injury.

Hubbard improved her total to 285kg in finishing sixth at the 2019 world championships in Thailand.

The global coronavirus pandemic put paid to any prospect of international competition for Hubbard in 2020.

So how will she fare at Tokyo?

Hubbard is currently ranked seventh in the IWF”s women’s +87kg division, headed by China’s 21-year-old 2019 world champion Li Wenwen and Robles, the American who beat Hubbard to the 2017 world title.

But she produced the fourth highest total in qualifying.

To keep her gold medal hopes in perspective, Wenwen, who weighs 150kg and is half Hubbard’s age, lifted a total of 332kg in 2019 – 47kg more than the veteran Kiwi, the oldest lifter at Tokyo.

Despite all the controversy that still swirls, there is no doubting Hubbard’s love of lifting.

“Laurel is an astute student of the sport and technically very good with the lifts,” New Zealand Olympic Weighlifting Federation president Richie Patterson, a double Commonwealth Games gold medallist and three-time Olympian, said this week.

Hubbard will need to be at her best to achieve her goals in Tokyo at what could possibly be her one and only shot at the Olympic Games.

The reaction to her selection means Hubbard will have to display courage both on the weightlifting stage and in the media mixed zones.

She has, in the past, displayed an almost sanguine acceptance that people will be polarised about her presence.

“People believe what they believe when they are shown something that may be new and different to what they know, it’s instinctive to be defensive.

“It’s not really my job to change what they think, what they feel and what they believe. I just hope they look at the bigger picture, rather than just trusting whatever their gut may have told them.”

Hubbard has never seen herself as anyone else, insisting: “I’m just me.’’