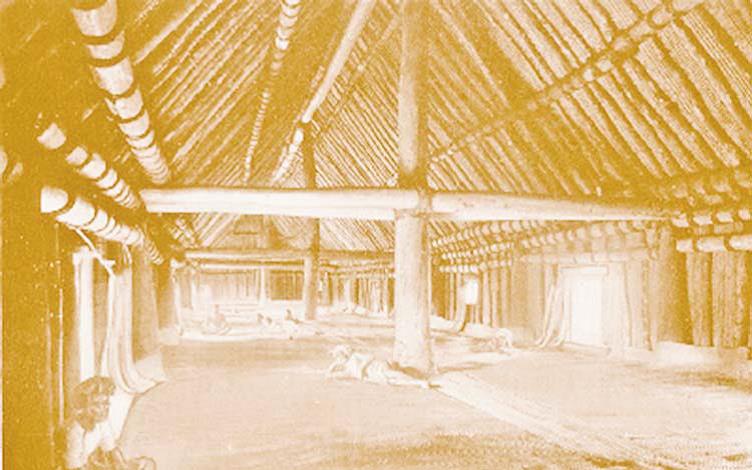

In every traditional village in old Fiji, there were many different types of thatched dwellings called bure, each designed according to their owners, purpose or function.

While the temple was the tallest and the chief’s home – the grandest, the bure-ni-sa was the biggest.

It was a temporary dwelling place for young men, much like today’s boys’ dormitory or bachelor’s quarters.

Some history writers even referred to it as a guest or club house.

The bure-ni-sa, or unmarried man’s house, was respected like an institution.

Decades after the new religion and government was accepted among natives, the bure-ni-sa still existed as a part of the social life of the village.

An Anthropologist, Basil Thomson, in The Fijians- A Study of the Decay of Custom, described it as “men’s “club” during the day and the men’s sleeping in a house at night”.

No woman could enter it.

Doing so would be a grave breach of customary law.

In those days, young boys below the age of puberty we not dressed.

They ran around nude and were still required to sleep with their parents at home.

But after circumcision they wore the malo, a white “perineal bandage” made out of masi bark cloth.

The malo was worn around the waist and between the thighs.

It signified that its wearer was a man and no longer a boy.

Malo wearers could not live with their parents anymore.

Once they were circumcised, the young men were taken to the bure-ni-sa at nightfall.

They slept there under the watchful eyes of elders who either had no home of their own or had adopted the bure-ni-sa by choice.

When the young man was old enough to marry, his mother chose a wife for him from among his concubitant (cousins he was betrothed to marry) cousins, especially the daughters of his mother’s brother.

Immediately after the marriage the young man moved from the bure-ni-sa and expected to live in a house of his own or again with his parents.

As soon as his wife gave birth, he was again banished to the bure-ni-sa for the entire suckling or breastfeeding period, which lasted from two to three months.

During this whole time, unless he had more than one wife, he was expected to live a life of celibacy.

Many young fathers found this custom annoying.

However, for a chiefly family, apart from having several wives, a man was merely confined to a separate house after his child was born.

He never saw the bure-ni-sa again after marriage.

Burenisa’s dual purpose

So the bure-ni-sa was closely linked to the unwritten laws and social order in the family.

It played a role in maintaining the population of the village.

Thomson said the bure-ni-sa served a dual purpose.

“With the girls of the tribe sleeping with their parents, and the young men being practically incarcerated every night under the eyes of their elders, there was little opportunity for immorality before marriage,” he noted.

On the other hand, with the duties of defence, fighting, providing food and fishing to contend with, the young men had little time for “philandering”.

Many elders often asserted that it was rare for a girl in the 1800s to “have lost her virtue before marriage”.

Any sexual immorality that took place was often between the “young men and the older married women”.

But the most important role played by the bure-ni-sa was allowing the separation of the parents of a child during the breastfeeding period.

When Thomson asked villagers to give reasons behind the decrease in their numbers, villagers blamed the breaking down of this custom of abstinence as the principal cause.

They said when breastfeeding mothers and their husbands lived together again quickly the quality of the mother’s milk was affected.

Not understanding the true cause that lay behind this belief, Europeans, medical men as well as missionaries, treated the opinion with contempt.

The missionary, Rev. J. P. Chapman, described this custom of abstinence during the suckling period as an “absurd and superstitious practice.”

Thomson said this showed that Christianity, though introduced with good intentions, ruffled the way of life of the early Fijians.

“The teaching of the missionaries, who believed that the only perfect social system was to be found in the English mode of family life…,” he said, “…broke down the custom of the bure-nisa in most parts of Fiji, except the montane and highland districts where it remained for some time.

White men’s influence led to the removal of something which the men had long found “irksome”.

Men’s club house and suckling

The Fijian word, dabe or save, referred to the sickly health and stunted growth experienced by child whose parents slept together too soon after its birth.

The symptoms of dabe were general physical weakness in the child, accompanied with an enlargement of the abdomen, similar to that of an under nourished child.

The infringement of the rule of abstinence was described by Bauans by the slang word, kuru vou.

During the period of suckling, from 12 to 36 months—the mother abstained from cohabitation for fear of impoverishing her milk.

This was mere superstition.

The real truth was, a rapid second conception while a baby was still being breastfed, caused the child to be prematurely weaned.

“While the mbure-ni-sa still existed, secret cohabitation between the parents was made the more difficult by the custom of young mothers leaving their husband’s house and living with their relations for a year after the birth of a child…,” Thomson noted.

However, since the English family life was adopted, husband and wife were no longer separated.

The requirement to follow rules on abstinence, as prescribed by ancient custom, was removed.

The health of the child was closely watched for signs that showed the parents had failed to stay away from each other.

Once the child bore the price of the parents’ iniquity and showed signs of dabe, the mother was required to wean the baby immediately.

If this was done prematurely, it was called kali dole.

Since the early Fijians had no artificial baby food, like the ones sold in supermarkets today, the sudden weaning affected the child’s health.

No artificial food for infants

There was nothing in old Fiji between the mother’s milk and solid vegetable foods.

Until the digestive organs were fit to digest sold foods, the child was breastfed.

Among European women menstruation rarely returned during the period of suckling.

There was therefore no particular danger to the child in cohabitation during this period.

If conception took place, the child was easily brought up upon artificial diet.

With Fijian women, however, menstruation often recommenced at the third or fourth month after birth.

Cohabitation, even at this early stage, often resulted in a second pregnancy.

“The mother is physiologically incapable of nourishing at the same time the foetus within her and the child at her breast, and the symptoms of defective nutrition become evident in the latter very soon after the new conception has taken place,” Thomson said.

The child was weaned at once, since it was too weak to undergo the strain of a change of diet.

It became dabe.

Thomson said he was once told by a midwife that the children of elderly men were less often dabe than those of young men.

This was because the older father, being less sexually active, was more likely to observe the rule of abstinence and stay away from his wife.

Thomson pointed out that nearly half the Fijian children born, died within the first year.

In many cases this death was caused by premature weaning and poor nutrition as a result of a second conception, Thomson believed that under the old “wise system of abstinence”, the mother had time to recuperate before she again bore the strain of maternity, but with the early death of her child she was at once pregnant.

Missionaries’ mistake

The custom of prolonged breastfeeding, the abstinence requirement and the existence of the bure-ni-sa showed that nature intended a Fijian mother to suckle her baby until it had developed the teeth necessary for chewing solid food.

On the other hand, modernity has resulted in artificial food for infants, leaving the mother free to bear the stress of a second pregnancy.

Thomson said: “Barbarism followed the law of nature and supported it by a customary law of mutual abstinence, but the customary law of the Fijians has been mutilated and has left them between two stools, not yet adopting the conveniences of civilisation and obliged, nevertheless, to do the high-pressure work of the civilised state without help.”

“The reproductive powers of the Fijian woman of to-day are forced, though her body is no better prepared by a generous course of food to meet the strain than when she was allowed to follow the less exacting course of nature for which only her body is fitted.”

Missionaries were responsible for breaking down these customs of abstinence, and regarded it as “absurd and superstitious”.

They did not recognise the important difference between European and Fijian society.

This Thomson said was the irregular and insufficient nourishment for the women and the lack of artificial food for infants.

Thomson said that missionaries should have devoted their efforts to reforming this before they discouraged a custom to meet the evils of a lack of cereals and milkyielding animals in old Fiji.

He said it was too late to go back to old customs and Fijian husbands would never again consent to enforced separation from his wife.

He added that the only feasible remedy was to improve the diet of the nursing mother and keep milk-yielding animals for their children.

“The early missionaries failed to see that in breaking down the bure system, and inculcating family life on the English plan, they were leaving the native to follow his own inclinations.”

- History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor