Policymakers and technology experts largely inhabit two separate worlds.

It’s an old problem, one that was referred to by academics as sciences and humanities, and pointed to the split as a major hindrance to solving the world’s problems.

Originally it was largely an interesting societal observation.

Today, it’s a crisis.

Technology is now deeply intertwined with policy.

We’re building complex socio-technical systems at all levels of our society.

Information systems dictate behaviour with an efficiency that no law can match.

It’s all changing fast; technology is literally creating the world we all live in, and policymakers can’t keep up.

Getting it wrong can be catastrophic.

Surviving the future safely depends on bringing technology experts and policymakers together.

Consider artificial intelligence (AI).

This technology has the potential to augment human decision-making, eventually replacing notoriously subjective human processes with something fairer, more consistent, faster and more scalable.

But it also has the potential to act in ways that are undesirable.

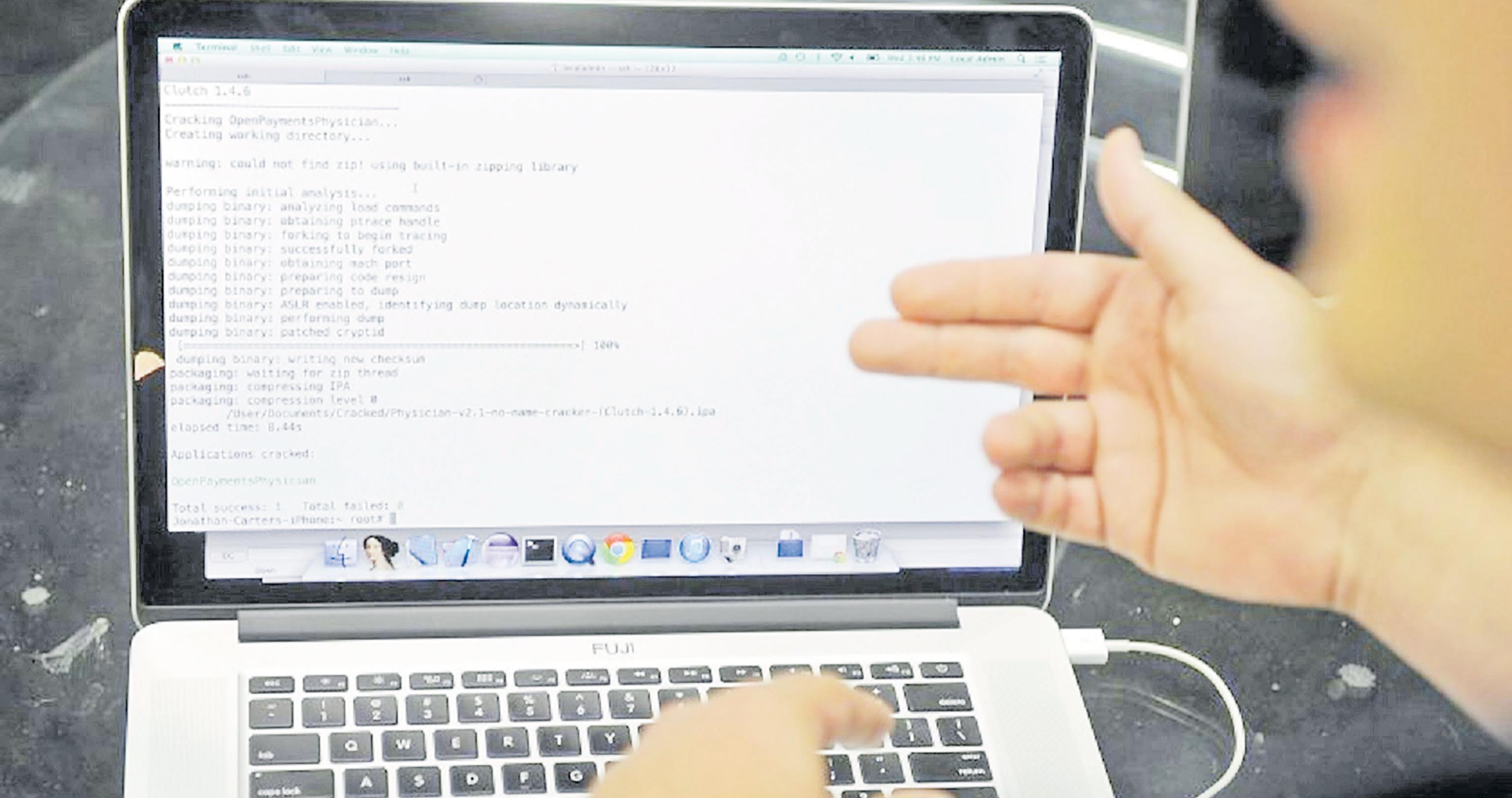

It can be hacked in new ways, giving attackers from criminals and nation states new capabilities to disrupt and harm.

How should government step in and regulate what is largely a market-driven industry?

The answer requires an understanding of both the policy tools available and the technologies of AI.

But AI is just one of many technological areas that need policy oversight.

We also need to tackle the increasingly critical cybersecurity vulnerabilities in our infrastructure.

We need to understand both the role of social media platforms in disseminating politically divisive content, and what technology can and cannot to do mitigate its harm.

We need policy around the rapidly advancing technologies of bioengineering, such as genome editing and synthetic biology, lest advances cause problems for humans and the planet.

We’re barely keeping up with regulations on basic food and water safety – let alone energy policy and climate change.

Robotics will soon be a common consumer technology, and we are not ready for it at all – in fact we may realise too late the integration of robotics into our personal lives and society without addressing the legal and policy issues.

Addressing these issues will require policymakers and technology experts to work together from the ground up.

We need to create an environment where technology experts get involved in public policy.

The concept isn’t new; there are already professionals who straddle the worlds of technology and policy.

They come from the social sciences and from computing science and engineering.

They will only become more critical as technology further permeates our society.

To make effective tech policy, policymakers need to better understand technology.

For some reason, ignorance about technology isn’t seen as a deficiency among our elected officials, and this is a problem.

It is no longer okay to not understand how the Internet, AI – or any other core technologies – work.

This doesn’t mean policymakers need to become tech experts.

We have long expected our elected officials to regulate highly specialised areas of which they have little understanding.

It’s been manageable because those elected officials have people on their staff who do understand those areas, or because they trust other elected officials who do.

Policymakers need to realise that they need engineers and technology experts on their policy advisory teams.

It is also no longer okay to discount technological expertise merely because it contradicts your political biases.

The evolution of public health policy is a good example.

Health policy is a field that includes both policy experts who know a lot about the science and keep abreast of health research, and medical practitioners and researchers who work closely with policymakers.

Health policy is often a specialisation at policy schools.

We live in a world where the importance of vaccines is widely accepted and well-understood and is written into policy.

Our policies on global pandemics are informed by medical experts.

However, health policy was not always part of public policy.

People lived through a lot of terrible health crises in the past before policymakers figured out how to actually talk and listen to medical experts.

Today we are facing a similar situation with technology.

Another parallel is public-interest law.

Lawyers work in all parts of government and in many non-governmental organisations, crafting policy or just lawyering in the public interest.

Lawyers at most reputable law firm are expected to devote some time to public-interest cases (pro bono); it’s considered part of a well-rounded career.

An engineering or tech career needs to look more like that.

Increasingly, we are watched not by people but by algorithms.

Google and Facebook watch what we do and what we say, and show us advertisements based on our behavior.

Google even modifies our Internet search results based on our previous behavior.

Smartphone navigation apps watch us as we drive, and update suggested route information based on traffic congestion.

More seriously, law enforcement and security agencies sometimes monitor our phone calls, emails and locations, and then use that information to try to identify and track criminals or terrorists.

Of course, any time we’re judged by algorithms, there’s the potential for false positives.

You are already familiar with this; just think of all the advertisements you’ve been shown on the Internet, based on some algorithm misinterpreting your interests.

In advertising, that’s okay.

But that harm increases as the results become more important: our credit ratings depend on algorithms; how we’re treated at airport security does, too.

And most alarming of all, drone targeting is partly based on algorithmic surveillance.

These days, saving highly personal data online is dangerous.

Location data reveals where we live, where we work, and how we spend our time.

If we all have a location tracker like a Smartphone, correlating data reveals who we spend our time with—including who we spend the night with.

Our Internet search data reveals what’s important to us, including our hopes, fears, desires and secrets.

Communications data reveals who our intimates are, and what we talk about with them.

I could go on.

Our reading habits, or purchasing data, or data from sensors as diverse as CCTV cameras and fitness trackers.

Saving personal data is also dangerous because many people want it.

Of course companies want it; that’s why they collect it in the first place.

But governments want it too.

Our governments spend millions of our taxpayers’ dollars collecting and storing our personal data for National Identify purposes, taxation purposes as well as for national planning.

Foreign governments can covertly just come in and steal it.

When a company with personal data goes bankrupt, it’s one of the assets that get sold.

Saving personal data is dangerous because it’s hard for companies to secure and failing to secure it is damaging. It will damage the company brand and reputation, reduce a company’s profits, reduce its market share, affect its stock price if listed, cause it public embarrassment, and may even result in expensive lawsuits or criminal charges.

We can be smarter than this.

We need to regulate what corporations can do with our data at every stage: collection, storage, use, resale and disposal.

We can make corporate executives personally liable so they know there’s a downside to taking chances.

We can make the business models that involve massively surveilling people the less compelling ones, simply by making certain business practices illegal.

Data is a toxic asset.

We need to start thinking about it as such, and treat it as we would any other source of toxicity.

To do anything else is to risk our security and privacy.

I wish you all blessings, stay safe and secure in both the physical and digital worlds this 50th anniversary independence day.

Ilaitia B. Tuisawau is a private cybersecurity consultant. The views expressed in this article are not necessarily shared by this newspaper. Mr Tuisawau can be contacted on ilaitia@cyberbati.com