There is a beauty about the way old Fijian songs were composed and sung. Fijian songs tell stories, just as history was recorded and passed down in stories and songs through the ages.

They tell stories about places, things, people, events, and relationships, and they come to life in the music. The world wars of the last century caused some of the greatest destruction, and some of the biggest stories in living memory.

These great conflicts established the superpowers of the world order that is recognisable today, and it began the end of the British Empire. When World War I was declared, the British Government would only accept recruits from Fiji on the basis that they were subjects of pure British descent.

The first Fijian contingent departed in January, 1915, for Britain where they received further training and fought in the battles of Flanders. Nine lost their lives and 31 were wounded, and a second contingent left for Britain in July of that same year.

According to an article by Jan-Hai Te Ratana, team leader of outreach and community learning at the Aranui Library in Christchurch, New Zealand, the colonial authorities at the time did not wish to be held responsible for aiding in the extinction of indigenous Fijians after a great portion of the population had been wiped out by bouts of exposure to minor European illnesses.

These bouts of disease had already left the indigenous Fijian population decreasing at an unexpected rate.

After serving on the front lines with the French Foreign Legion, Fijian statesman Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna began drumming up support for Fijian participation in the great war, and in 1917, they were allowed to join the ranks of the British forces.

When World War II broke out in 1939, Fijians lined up to volunteer for the war effort under the Fijian Military Forces – then commanded by a New Zealand Army officer under a 1936 agreement with the British Government that New Zealand assume responsibility for the defence of Fiji.

Two infantry battalions and commando units went to fight for the allied cause against the Japanese in the Solomon Islands, seeing service with United States Army units in Guadalcanal and Bougainville.

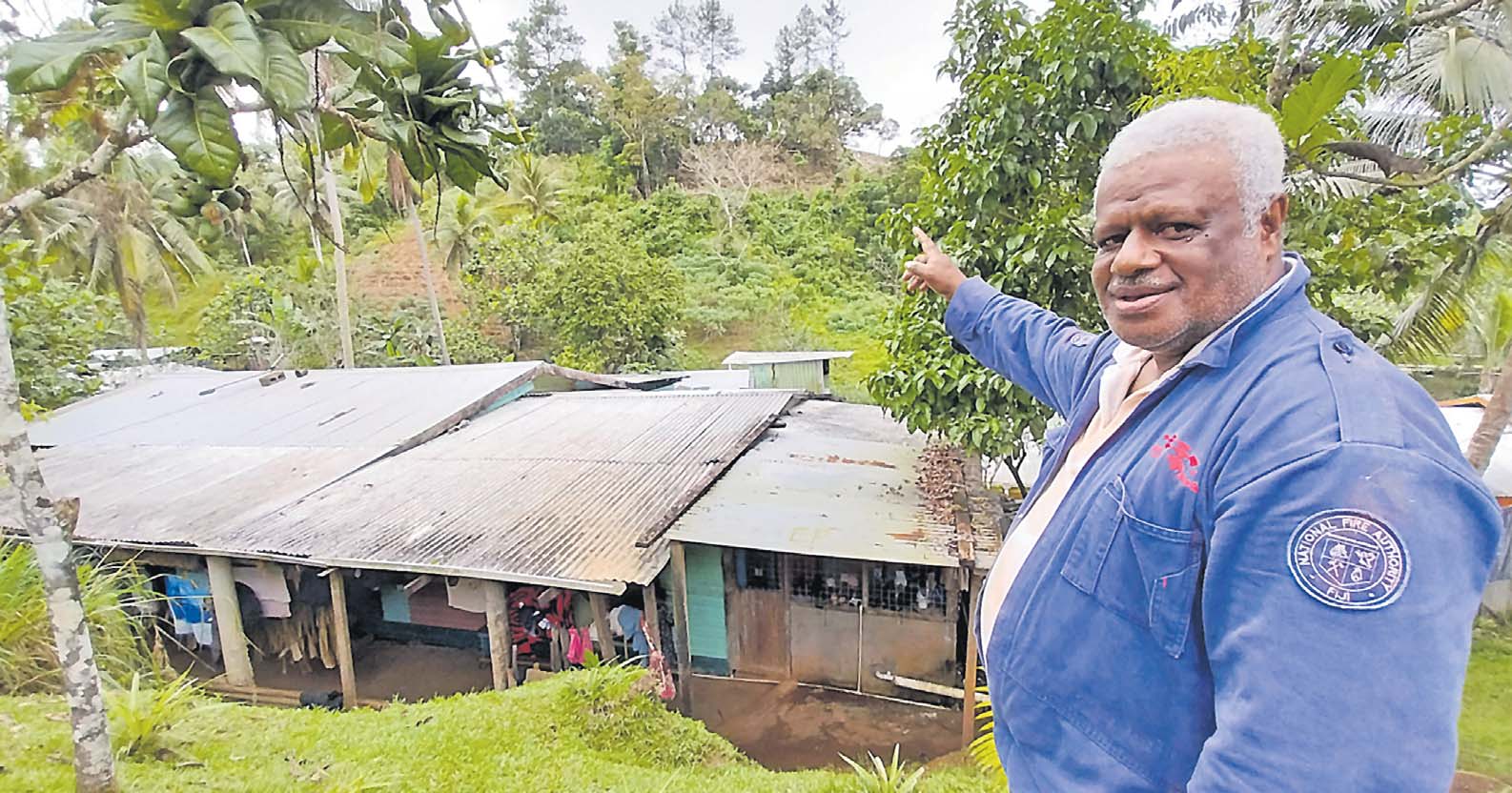

One of these soldiers came from Nakini Village in Naitasiri. “His name was Solomone Koroiwaca and he was a drill sergeant in the Fijian Military Forces,” says Taitusi Savutila.

“He was my uncle, my father’s elder brother.” Mr Savutila, a retired civil servant with the Department of Agriculture, says when his uncle was leaving for the Solomon Islands, he wrote a song for his wife.

“The song is called Me yacova ni waqa na cina mai Bolatagane,” Mr Savutila says.

It became a classic piece of Fijian music, popularised by the sigidrigi group Tegu ni Nakanacagi, a group from Nakini Village in the 1960s. The group was named after a hill called Nakanacagi that flanks Nakini’s western side, and separates it from the neighbouring Naganivatu Village.

“The song was based on a popular English song at the time, When the Lights Go On Again (All Over the World),” says Mr Savutila.

Composed during World War II, the song was written by Bennie Benjamin, Sol Marcus, and Eddie Seiler. It was first recorded by Vaughn Monroe and reached number one on the charts in 1943, expressing a hope for the end of the war, and titled for the refrain found throughout the song.

The refrain is a reference to a statement attributed to British statesman Sir Edward Grey, that the lamps were going out all over Europe.

During the Blitz in Britain, blackouts were imposed to combat bombing raids by the German forces. If there were no lights, they could not see the villages, towns, and cities, and would not have a visual on their targets.

The lyrics go: “When the lights go on again all over the world, and the boys are home again all over the world, and rain or snow is all that may fall from the skies above, a kiss won’t mean ‘goodbye’ but ‘hello to love’.

“When the lights go on again all over the world, and the ships will sail again all over the world, then we’ll have time for things like wedding rings and free hearts will sing, when the lights go on again all over the world.”

Mr Savutila says his uncle wrote the Fijian version in reference to his own separation from his wife.

“My aunt’s name was Mereseini Tasere and she was from Vuci, Tokatoka, Tailevu.

“My uncle wrote it for his wife when he left to fight the Japanese in the Solomon Islands in 1944 because they were separated from each other by the war.

“He heard that English song and wrote his version based on the reference to the lights coming on again in Britain.

“The lights had to be turned off because of the bombing raids that were going on in Britain at the time.

“In the song, he tells my aunt that he would return when the lights came on again in Britain, which would mean the end of the war.”

Solomone Koroiwaca passed away about four years ago, and when The Fiji Times visited Nakini, Mr Savutila said the last surviving member and lead guitarist of Tegu ni Nakanacagi, Senitiki Vosawale, passed away last year.

The Turaga ni Koro for Nakini Village, Manoa Koroiwaca — Mr Savutila’s brother — says Senitiki was named after their father.

“He went to work overseas and returned with a guitar and that was how Tegu ni Nakanacagi got its start.”