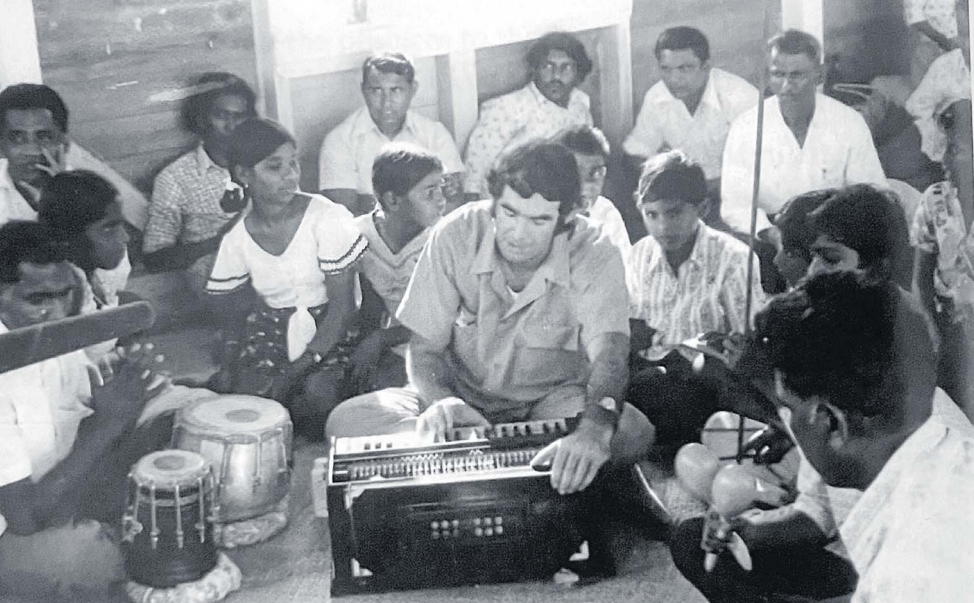

As we bid farewell to Naleba where Father Frank Hoare served as a Columban missionary, we turn now to his own words, reflections penned nearly five decades ago, chronicling the richness, discomfort and joys of his early years as a priest in Fiji.

These journal entries offer a window into the personal and pastoral journey of a man who chose to live not above, but among the people he served.

They all sound the same!

“It is great to have a chance to learn the Fijian language and culture,” Father Hoare wrote.

By 26 March, 1977, Fr Frank Hoare had already been in Fiji for two years.

Following his assignment in Naleba and Labasa, he was immersed in the study of standard Fijian in Suva.

As part of his formation, he was sent to Naililili to assist Fr Seamus McMahon during Holy Week.

It was a challenging and transformative time for the young Irish priest, who was still wrestling with the complexity and melody of the Fijian language.

His first confessions in Fijian were a test of both humility and compassion.

One particularly emotional encounter with a woman, who wept as she shared her burden, left Fr Hoare feeling inadequate.

“I was embarrassed at not understanding the problem, and I had very little comfort or advice to offer.”

In that moment, the limits of language became deeply human.

That same night, back at the presbytery, he switched on the radio.

To his surprise, he heard a familiar voice singing a Hindi bhajan accompanied by a harmonium.

It was his own voice, part of a recording he had made three months prior for Radio Fiji during a Hindi interview with Thomas Ambika Nand.

Curious, he turned to Fr McMahon and asked, “Do you know who’s singing?”

The elder priest listened, bemused, and replied, “All those Indian singers sound the same to me!”

It was a light-hearted moment in a week of intensity, and one that reminded Fr Hoare of the multilingual, multicultural fabric of Fiji and of his own growing place within it.

Wise as serpents and simple as doves

By April, Fr Hoare was deepening his understanding of Fiji’s missionary landscape, especially in relation to the Indo-Fijian community.

He wrote of the late Archbishop Pearce, who had served as Fiji’s second archbishop from 1967 to 1974, and had made a bold push to evangelise Fiji’s Indian population by reaching out to seminaries in India.

In response, a number of Indian priests and seminarians, including members of the Indian Missionary Society, answered the call.

Among them were also French Canadian Capuchins who had previously worked in India and were assigned to parishes like St Agnes in Samabula.

Fr Hoare sought guidance from one of them, Fr Dion, about how best to approach Indian evangelisation. What he received was a cautionary tale.

“Don’t do what we Capuchins did in India,” Fr Dion told him.

He recounted how the Capuchins had arrived with resources and built a large house.

Their affluence created a gulf between them and the people. Eventually, they had to erect a high wall and locked gates to keep out the daily flow of those seeking help.

But that physical barrier became a spiritual one too.

“They came begging from us every day.

“And in the end, we realised we had cut ourselves off from the people.”

Fr Dion’s advice to Fr Hoare was simple and radical: come with nothing. Ask the people for help. Let them see your humility.

“Then,” he said, “they would have shared what they had with us and come to us for spiritual enlightenment.”

This story left a deep impression on Fr Hoare.

It challenged the assumptions of missionary life and affirmed a model of ministry rooted in poverty, presence and proximity.

Fijian ministry 1977–1978

In the broader narrative of his early years in Fiji, the entries from 1977 to 1978 reveal a deepening relationship with the Fijian people and culture.

After his language course and time in Naililili, Fr Hoare spent two months in the village of Nacamaki on Koro Island.

He lived modestly in a room behind the village hall. Each day, he said Mass in Fijian and joined a different family for meals, an intentional practice that helped him become not just fluent in the language, but fluent in the unspoken customs of hospitality, reverence and communal life.

Later, he was appointed to Nabala Parish, southeast of Labasa.

Nabala was a vibrant mission area with a church and a secondary school.

A new parish center and primary school were being built inland at Vudibasoga during that time.

It was a short, eight-month appointment before his first holiday back to Ireland, but it marked the culmination of a formative period, where learning, language and lived experience converged.

What Fr Hoare’s writings from 1977 illustrate a priest in formation, not just academically or religiously, but cross-culturally.

In learning Fijian, singing Hindi hymns, and absorbing the wisdom of older missionaries, he was being shaped for a life of service grounded in empathy and understanding.

n Next week, we will run through June and July 1977, as Fr Hoare finally sits with the iTaukei communities.