In our last article (21/06/25), we focused specifically on pre-cession jockeying for power in Fiji and, in particular, the struggles, strategies and machinations of Bau in it. In this regard, we centralised the role of Ratu Seru Cakobau at that time. After all, the happenings in and around Bau shaped the future of Fiji. Let’s proceed from where we left off last.

Tanoa banished, Seru in Bau

Readers will recall that Ratu Tanoa was treacherously forced to flee to Somosomo on Taveuni because of a conspiracy in Bau involving Komai Nabaubau (of the Rokotui Bau household), Ratu Navuaka, Ratu Caucau, Ratu Mara Kapaiwai and Ratu Namosimalua.

The conspirators planned to assassinate Ratu Tanoa, but Ratu Namosimalua secretly informed him of the plot, and he was able to slip the impending assassination

A war party pursued Ratu Tanoa and at Somosomo, traditional approaches were made to Ratu Yavala, the reigning Tui Cakau, but he refused to hand over Ratu Tanoa. That war party then returned to Bau and installed Ratu Tanoa’s half-brother, Ratu Ramudra as vunivalu.

This was not a gesture of magnanimity, but a carefully planned strategy because the 500-pound Ramudra was virtually useless and was later popularly referred to as Vunivalu Davodavo.

After Ratu Tanoa was effectively banished to Somosomo, the conspirators in Bau continued to manipulate and plot for power and influence. Ratu Seru, who had returned to Bau as a young boy after a stint in Rewa, with his mother’s elder sister who was the wife of the Roko Tui Dreketi, and a few years on Gau, was not harmed even though he was included in the initial assassination plot.

He appeared to have the patronage of the Rokotui Bau, whose power had virtually dissipated even though his influence was apparently still acknowledged.

He also had covert support from Ratu Namosimalua who had powerful links to Viwa. It needs to be noted that Seru was a vasu of the former nobility, the Nabaubau of the Rokotui Bau clan. Fijian historian, Setareki Koto says that “it seems that Ratu Cakobau secured protection from the Roko Tui Bau and his maternal uncles of Nabaubau” (Sahlins, 2004, p.252). Thus, Seru would have had all the protections and privileges accorded the vasu within the tapestry of relationships that existed at the time.

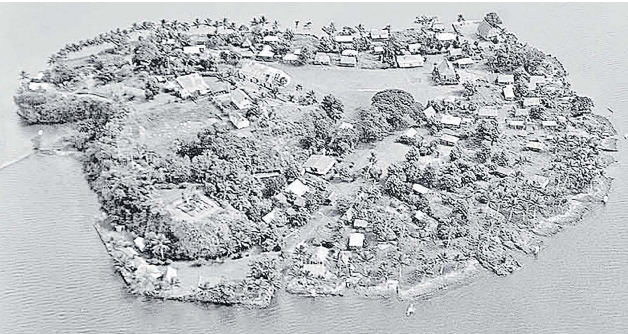

While on Bau, Seru often appeared innocuous and too playful, but this was apparently a carefully crafted “front” as he continued to forge further alliances with powerful forces both within Bau and outside (especially with Rewa where his father had a wife, Adi Qereitoga). Records show that towards the end of 1835 Ratu Tanoa joined his wife Adi Qereitoga after leaving Somosomo and was accorded protection by his wife’s brother, Ratu Kania, the Roko Tui Dreketi, who was also actively campaigning to have him reinstalled as Vunivalu in Bau. Thus, the Bau Rebellion of 1832 to 1837 was successfully suppressed largely because of these manoeuvres and alliances especially with Ratu Kania (Rewa) and the Lasakau (fisher-warriors). Of course, this rendition of Bauan/Fijian history cannot be complete without mention of the fire that engulfed the rebel-held part of Bau and sent them fleeing the island. That legendary fire has numerous musings and interpretations around it.

Ratu Tanoa, thus returned to Bau after Seru’s decisive victory over the “rebels of Bau” in 1937. One question that continues to intrigue researchers is: who exactly were the Bau Rebels of 1932-1937? The historical rivalry between the Vuaniivi and the vunivalu offers one avenue to understanding this, but the Vuaniivi were a spent force when Ratu Raiwalui died in 1828 and following this there were other factions that had begun to morph into a formidable force against the vunivalu. Among these was Komai Nabaubau (of the Rokotui Bau household), Ratu Navuaka, Ratu Caucau, Ratu Mara Kapaiwai and Ratu Namosimalua. Another dimension is offered by focusing on the marital links and vasu relationships that were forged by (especially) Ratu Tanoa through his nine (recorded) wives. Powerful ambitions also lay among these scattered blood relatives. These were to continue after 1837 and influence contemporary politics in Fiji.

Tanoa returns

After carefully going through historical records, it can be hazarded that when Ratu Tanoa returned in 1837, he effectively took over both the side-lined position of Rokotui Bau and the more executive position of vunivalu. The rebels had installed the obese and ineffective Ratu Ramudra as vunivalu, but the real power lay behind that throne.

The position of Rokotui Bau had receded after the death of Ratu Raiwalui. This blurring of the lines in practice allowed Ratu Seru to move into the position of vunivalu while Ratu Tanoa (his father) receded to the ceremonial role of Rokotui Bau. It needs to be noted that the term “role” rather than “position” is being used here. In order to understand this better, let’s look at the usual structure of other kingdoms in Fiji.

These kingdoms usually had a dual kingship structure with a sacred king and a war king. The war king was subordinate to the sacred king. In Bau, historically the sacred king was also the Rokotui Bau while the war king was the vunivalu. However, later in Bau “the de facto rank of the two kings had been reversed, at least since the beginning of the nineteenth century and probably for much longer. For all practical purposes, including even ritual purposes outside the principal temple of the kingdom, the vunivalu ruled in Bau” (Sahlins, 2004, p.198). This is what allowed Seru to take up executive authority while his ailing father receded into a largely ceremonial and advisory role after 1837.

Personal explanations

I stop this rendition here for now as I need to explain a few things before we proceed to post-1837 Bau. Readers will have noted that I have begun to put more details into my more recent articles. This is because at a recent meeting at USP a senior academic administrator, who has never written a newspaper column, said the following: “writing newspaper columns and feeling big is not important. That is not research”. I was simply dumbstruck because I am the only regular columnist from USP, and his remarks were obviously directed at me. I was also feeling at a loss because our career progress is linked to not only our teaching, but more so to our research and publications.

When I looked at him, he felt obliged to explain that our publications need to be caught in SCOPUS which, according to Wikipedia, is “one of the largest abstract and citation databases for peer-reviewed scientific literature”.

We, like he, often forget that this is just ONE OF THE databases. It is also heavily commercialised with annual income running into the billions. Moreover, it does not capture research that falls outside its coverage.

Books residing in libraries by researchers and academics who are now prominent real Professors have no value in this system where SCOPUS dictates who gets recognised and who gets ignored.

There are prominent newspaper columnists who have international intellectual reputations like: Leslie Cannold (The Age Melbourne; The Sun Herald), Henry Isaac Ergas (The Australian), Gwynne Dyer (Canada), Shashi Tharoor (India), Paul Krugman (The New York Times), Hugh Cortazzi (The Japan Times), Wadan Narsey (The Fiji Times), and the list goes on – these, according to the interpretation that centralizes SCOPUS, were/are not researchers. In other words, they did/do not conduct meaningful research to write their widely read columns or podcasts.

After thinking through this, I decided to up the ante and began populating my columns with details that emphatically proved they were researched. Just yesterday as I sat in the USP Library, which has the largest collection of Pacific Research in its renowned Pacific Collections section, I lamented how my painstaking digging through records of pre-colonial Fiji could not qualify as research. We all know that life can be unfair, but we also know that there is always light at the end of the tunnel. When I walked out of the USP Library and into the foyer yesterday, I couldn’t suppress the spring in my feet as I headed for my PC to write this column.

These are part of my labour of love for people who are interested in pre-colonial Fiji, Bauan politics and the numerous other topics I write on. If they don’t involve research, I must be a genius. I stop here for now; you be the judge.

n Dr SUBHASH APPANNA is a senior USP academic who has been writing regularly on issues of historical and national significance. The views expressed here are his alone and not necessarily shared by this newspaper or his employers subhash.appana@usp.ac.fj