Who we are as indigenous people is intrinsically linked to the ocean — our histories, identities, and way of life. But if deep-sea mining is allowed to happen, all of these will be brutalised, violated, and trampled upon. We will not stand for that.”

Indigenous Fijian cultural expert and scholar Simione Sevudredre emphasised this key point during a dialogue session on Deep-Sea Mining (DSM) earlier this week, where he also argued against all forms of mineral exploration and extraction in the Pacific Ocean.

Sevudredre emphasised the almost symbiotic bond between the indigenous Fijian people and the ocean, which endures to this day.

While our ancestors relied upon the ocean as a source of food and resources, they also traversed its length and breadth with precision as skilled navigators, using the stars, wind, currents, and birds as guides.

However, the ocean was just as sacred as the land. It was a space that most of the gods of ancient Fiji called home and was believed to be the final resting place for the spirits of departed ancestors.

Sevudredre also called for greater recognition of what he termed ‘indigenous science’.

He said that much of the secular scientific theories taught today to explain certain phenomena in Fiji were already well known to ancient Fijians, though conveyed through myths and legends.

“The best teacher is able to take complex concepts and break them down so that even the slowest learner can understand — that’s where our ancient myths and legends come from.”

The ocean – A sacred realm

Sevudredre shared that indigenous Fijian society derived various notions of its identity from the ocean, an example of which was the chiefly and tribal honorifics that existed to this day.

“His Excellency, the President, is also known as the Tui Cakau, which literally means ‘King of the Reef’.

“This tells us that the original person, the first Tui Cakau, came from the ocean,” he said.

Sevudredre also described the honorific of Bua Province in Vanua Levu, which refers to a sunken reef called Cakaunitabua.

He referenced a clan on the island of Oneata in the Lau group whose honorific is linked to a reef named Bukatatanoa.

“There is also a clan on an island closer to Tonga, Ono-i-Lau, whose honorific also refers to a reef— Cakauseyawa.”

“There’s also a clan on Vanua Balavu called Yavusa Waitui, or ‘clan of the sea’,” Sevudredre said.

The old word for ocean was Lau, and there is a clan tied to this term in Dawasamu, as well as a yavusa Lau in the Solomon Islands.

The term Lau is also the name of Fiji’s oceanic province, the Yatu Lau or Lau Group.

Sevudredre further revealed the reverence indigenous Fijians held for ancient sunken islands—one being Davetalevu, located off Moturiki in Lomaiviti, and another called Burotu or Burotukula, believed to have existed alongside Matuku in Lau.

“The ocean was also a place where our sentinels, whom our ancestors have framed as our totems, roamed — the sharks, turtles, trevally fish, octopus, and stingray. These are the ancestral sentinels we identify with.”

Sevudredre highlighted how, in Fiji, two categories of chiefs existed: those who were land-based and those who emerged from the sea, who, upon installation, took a ritual bath in the ocean.

This distinction extends to the two categories of people in indigenous Fijian governance — Kai vanua and kai wai. Special norms and customs of mutual respect exist between these two groups, forming the basis of indigenous society.

“Before Christianity arrived, there was no concept of heaven and hell within indigenous society. It was believed that when ancestors died, their soul would stand on the fort or hill close to the village and look for a place to leap into the sea, called ‘na i cibaciba’— the leaving place.”

This belief suggested that the soul returned to the ocean after death. Hence, the concept of the underworld or bulu — the ocean floor—was where the sleeping ancestors lay.

The historical knowledge shared by Sevudredre makes it evident that the ocean, in its entirety, holds immense cultural and spiritual significance for the indigenous people of Fiji.

He reiterated that indigenous Fijian social realism was reflected in language. The fact that there is no indigenous word for mining clearly demonstrates how it is a completely alien and unwanted practice.

“Mining has never been—and never will be—a part of our vocabulary because the process involves entering the tabu zone, bulu, where our ancestors sleep.”

“Our notions of identity, the history of our ancestors, the lineages of our chiefs, the protocols that dictate our behaviour and define our responsibilities, and our tribal customs are all derived from the ocean,” Sevudredre emphasised.

He further reiterated that indigenous Fijians would never allow this sacred space—the ocean, to which much of their history and identity is tied—to be violated and disrespected.

Indigenous Fijian cultural expert and scholar Simione Sevudredre.. Picture: TUMELI TUQOTA

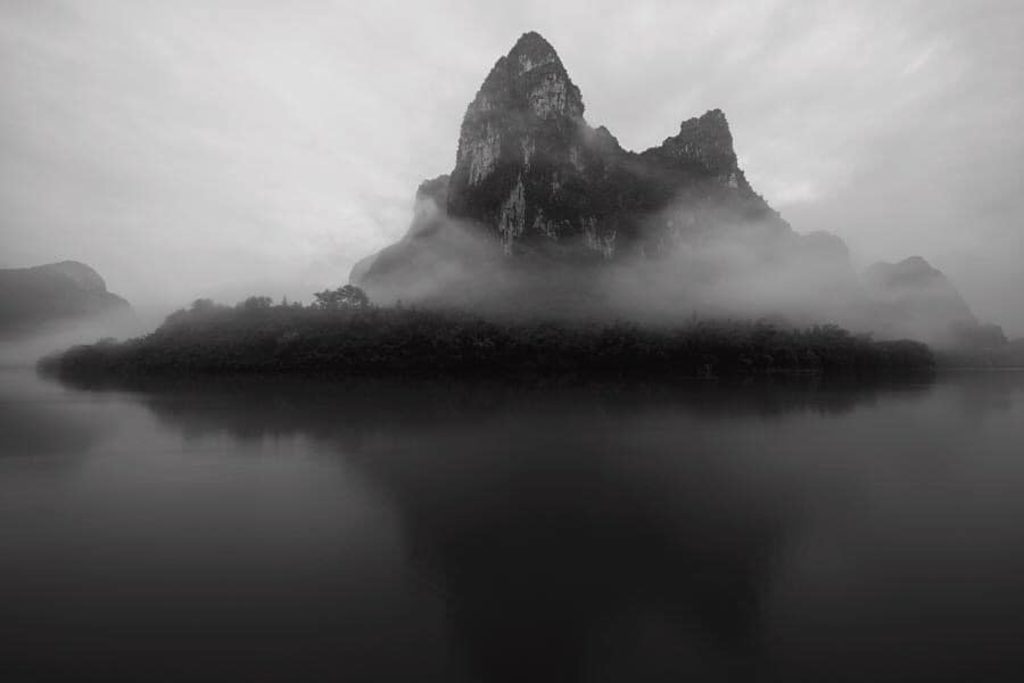

Burotu or Burotukula – Legend has it that the island was home to some of the most beautiful women in the world.

Picture: FACEBOOK/MATANITU VANUA

Greenpeace activists protest against deep-sea

mining in the Pacific.

Picture: Marten van Dijl/Greenpeace