Part 4

On August 17, 1849 Captain John Elphinstone Erskine and his group arrived in Ovalau. They were received by several natives.

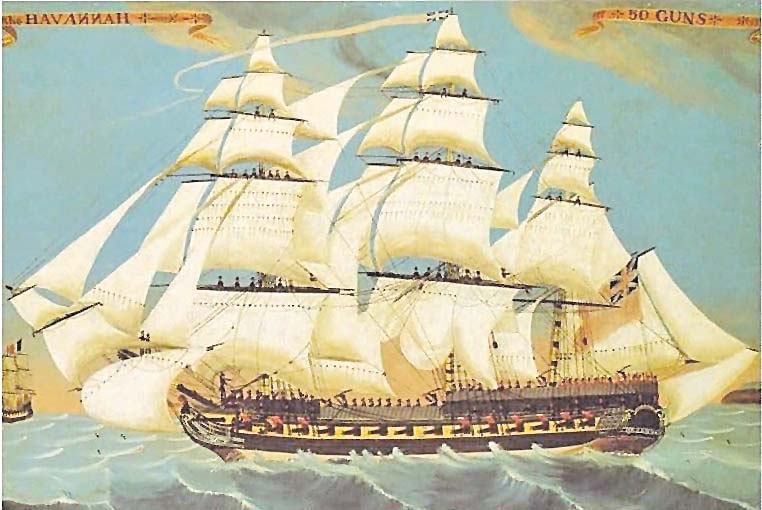

In this continuation of Erskine’s account of his time in Fiji, published in 1853 in the ‘Journal of a Cruise Among the Islands of the Western Pacific, in Her Majesty’s Ship Havannah’.

Erskine’s group had brought Navindi (Gavidi) and chief offerings of fish and food.

Erskine requested the presence of Tui Levuka on board.

“We found the chief’s canoe, one of moderate dimensions, alongside of the ship, and learnt that she had just arrived from Mokungai (Makogai), one of the small islands in the neighbourhood, she had been ordered for a supply of pigs, which I had requested Thakombau (Cakobau) to procure for our ship’s company,” Erskine stated.

A canoe from Viwa Island also arrived, which was to take Reverend James Calvert home. Before Calvert went, a conversation was held in the presence of both Gavidi and Cakobau on the subject of the approaching visit of the people of Somosomo people to Bau and ‘the disgusting habit of cannibalism generally.’

After Erskine’s serious conversation with Cakobau, through Calvert the intepreter, on issues of cannibalism and the mission stations of Bua and Nandi (Nadi), he became anxious and went on shore.

“A parting request for a bottle of brandy was delicately hinted on the part of Navindi, which I granted on condition of its not being opened on board, where they had already been fully entertained.

“On my return to the ship, an hour or two afterwards, I was, therefore, not a little surprised at the scene which presented itself on entering the cabin.”

There on the armchair sat Cakobau with his feet resting on another, dressed in the guardsman’s coat, his turban which was dirty and unchanged for three days.

He sat there with a look of satisfaction and on the table stood the brandy bottle. Cakobau, Gavidi and Tui Levuka couldn’t resist the temptation.

They were dressed in the finest clothes they had acquired on board. “I pretended to take no notice of the party, which probably hastened their departure in rather an unceremonious manner,” Erskine noted.

During Erskine’s walk on shore, he had visited the village of Levuka located a mile from the landing place.

“It consists of a considerable number of huts, huddled together without regularity, and enclosed by a mound of earth three feet in height, which is surmounted by a reed fence,” Erskine said in his description of Levuka Village.

“The whole being surrounded by a narrow and shallow ditch, serving both as a defence and a garden for taro, a plant requiring a damp situation.” Erskine noted that the village was filled with women and children.

The presence of a foreign ship had attracted the men to the beach where Tui Levuka had stationed an armed protection from mountain warriors of Lovoni Valley.

“The married women wore their hair in a variety of shapes, often in the mop-headed fashion of the men; in some instances sprinkled with dust or lime, resembling hair powder, and often stained various hues of yellow.

“Many carried their children on their backs, their little legs stretched out in an extraordinary degree to maintain their hold, their own bodies being generally covered with marks of scars, inflicted at different times, in sign of mourning for the death of relative.”

On August 18, Erskine engaged Simpson as the pilot of the ship and left for Nandi and Bua Bay where the two missionary stations were located.

“The missionary of the station, the Rev. David Hazlewood, soon came off in a whaleboat, bringing with him one or two Christian chiefs, who, as usual, expressed great pleasure at seeing us.

“I was glad to hear from Mr. Hazlewood that all was now quiet at his station, and that a disturbance which had taken place in April last, a report of which had induced me to come to Nandi, had passed over without leaving any fear of a recurrence.”

After engaging with the missionaries, the next day Erskine attended a service at the native church where there was a large congregation of about a hundred natives.

“At daylight this morning we embarked Mr. Hazlewood and his native friends, and, taking their boat in tow, ran down the coast seven or eight miles to So-Levu, where we sent a boat on shore for the chief.

“I had some conversation with him respecting the late demonstration against the Christians, to whom he declared himself perfectly friendly, as well as to all white men, a colony of whom (the same now on Ovalau) had resided in the neighbourhood for several years.”

Erskine showed the chief that there would be consequences if British subjects were mistreated and by way of illustrating, he had two shots fired at an object as a warning. After this interaction, Erskine and his party made sail to Bua Bay and got to learn of the progress of Christianity and visited a chief called Pita.

“My object in visiting this station having been to reassure the peaceable members of the mission, and to extend to them the protection due to British subjects, “I crossed the river with Mr. Williams to visit the chief of the village, Pita, or Tamai Vunisaa, halfbrother to Bachanamu, and warn him of the serious consequences of molesting Englishmen who were infringing none of the laws of the country.

“I explained to him the promise which had been made to me by Thakombau to take the protection of the Christians into his own hand.”

On August 27, after visiting other places they returned to Levuka for a final farewell visit before their departure from the islands.

“The boat which came to land the pilot brought off Tui Levuka and several of our friends to bid us farewell.

“Among the party was a young man we had not seen before, a brother of Navindi, who was pronounced by all, in spite of the darkness of his colour, to excel in manly beauty those of all the islands we had yet visited.

“He brought me a present from his brother of two Feejeean wigs, and a kind letter from Mr. Calvert.”

Erskine had also received a message from Cakobau stating that he had unintentionally left behind a blanket for him.

“A few small presents were distributed to the other chiefs; and our pilot and interpreter Simpson, whose conduct had been in every way satisfactory, was remunerated for his fortnight’s services by a sum of fifty dollars (about 10/.) with which he was perfectly satisfied.”

“The navigation of the Feejeean group has been rendered comparatively easy by the publication of the charts of the United States Exploring Expedition, which, however, are not supplied to Her Majesty’s ships, and of which I never succeeded in procuring a complete set.”

Erskine’s time in Fiji gave him the opportunity to learn about Fijian politics, the fate of shipwrecked sailors, the sandalwood trade, how the chief of Cakau was buried alive and a chance to observe their ways and compare it to the previous islands he had been to.

History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions.

Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor.