Thomas Williams was a Wesleyan missionary who experienced dark days during his first two years’ in Fiji and was far from prepared to encounter the indigenous people and their distinct ways.

In a book called ‘The Journal of Thomas Williams, Missionary in Fiji, 1840- 1853’, the details on his early life to his sea voyage and work in Fiji is shared.

The first volume of the book is edited by G.C Henderson and based on the written accounts of the missionary at Lakeba and Somosomo. The book notes that Williams was born on January 20, 1815 at Horncastle, Lincolnshire, England to John Williams and Jane Hollin- – shed.

Losing his mother and raised by a strict father, he was educated at a private academy in Lincoln and later worked at his father’s office as a clerk. He joined the Wesleyan society at 19, taught Sunday school, became a local preacher and volunteered as a missionary to Fiji in 1839.

Within that same year, he married Mary, a daughter of a farmer and together they sailed the seas, beginning his journey to the South Seas. Henderson stated that his first year in Fiji was one of ‘acute suffering’ and to some extent of ‘disillusionment.’

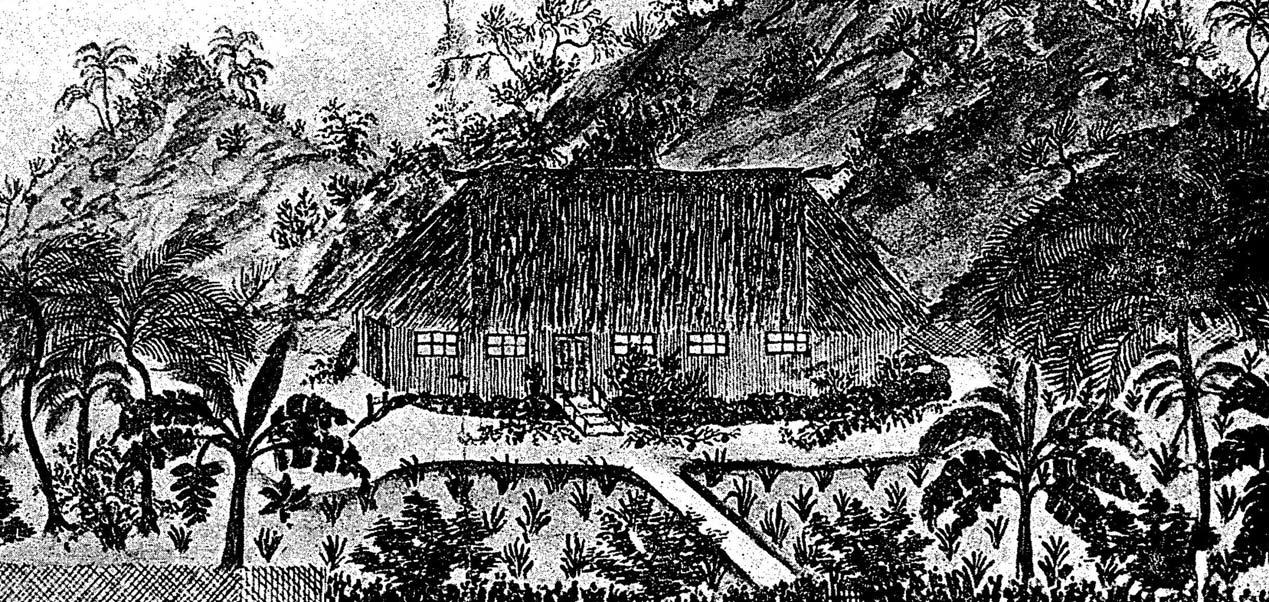

Bringing with him no furniture during his arrival, he shared the home of missionary Calvert and day and night worked at building a house until he was exhausted. Mission work was carried out in ways that were foreign and strange to him and the process of adapting to a new environment was painful.

“Travelling overland, he was exposed to the inconveniences and perils of tropical storms that it turned streams into torrents. On the sea he had to make voyages in frail canoes at greater risk of his life than he was, at first, able to encounter without dread,” Henderson wrote.

“Myriads of stinging mosquitoes irritated him in the daytime and sometimes banished sleep at night. “But he was not out of the wood yet. Adaptation to his new environment came slowly, and the work for which he had left home, friends and occupation was dragging.”

Few converts were made by him and his colleagues and the few that were attracted to the new religion did so because of the use of British medicine. “His peace of mind was to be rudely disturbed once again when a war, partly of his own making, broke upon him in 1849, the war between Heathenism and Christianity.

“For three years he saw his Christian followers despoiled, exiled, murdered, and he could do little to relieve them of their sufferings.” Williams began to discover that advances for peace would only encourage the natures to commit more crimes.

Therefore he began to wonder if his life in Fiji had been wasted. During his time on Lakeba he would mostly be accompanied by Calvert, preaching to the heathens and travelling to nearby islands converting as many Fijians as he could.

There was a particular incident when a rapid fire approached the chapel and houses, and the chief sent the people of the settlement to their help. Williams’ journal entry stated how they worked to eventually extinguish the fire, however, two Tongan heathens shouted, ‘let the chapel burn that we may fight.’

“Whilst the Feejeeans came to our help unarmed the Tonguese came with clubs, axes which caused unpleasant remarks from the fine race of men to whom we are sent.” During his visit to Waitabu, he conducted the ceremony of putting the first post in the ground which was equivalent to laying the foundationstone in England.

“The Waciwaci heathen have determined to assist the Waitabu Christians considering the work too great for so few persons.” On another occasion, one of the Tui Nayau’s wives died. Three different reasons were given by the gods to explain the cause of her death.

One was because “there was something amiss respecting the yagona (yaqona)”, second was because Tui Nayau had refused to give “a canoe to the people of Morley” and the third was because the “foreign God had taken her soul”.

“Amongst other absurd things said by this priest were these, ‘I and Kuba na Vanua only are gods, I am present in all places. I preside over wars and illnesses. But it is difficult for me to come here as the place is filled by the foreign God.”

Before his move to Somosomo on Taveuni and mission work at nearby villages, he shared how only God knew his toils and the results of his labours. “We have increased our numbers considerably, built several chapels, had the pleasure of witnessing four islands entirely renounce heathenism, introduced preaching into several towns and villages.

“Much prejudice has disappeared, and a better state of feeling towards us has been manifested by the people during the past three years.”

Williams continued to preach to the adults saying that in serving the devil, they would only “injure their bodies and souls, their families, and their land”.

“But oh, how lamentable the influence which Feejeean chiefs exert over their subjects, ‘Let our chiefs embrace religion first’ was the general cry.

“I noticed that during the whole of the time that Tui Vuna was drinking his yagona and the water after it his people continued clapping their hands in a very musical manner.”

His experiences changed perceptions of native sympathy even though Williams had an early impression that Fijians were ‘without natural affection.’ He recognised a combination of contrary qualities in their nature, “from courtesy and affection” at one extreme to “diabolical treacherous and murderous ambition”.

His encounter with Tuikilakila of Somosomo was one experience that altered this perception. He felt that although this typical Fijian who buried his father alive, had women strangled, and ate his fellow subjects, he still had love for his father and was fond of children.

“Many of those with whom I conversed heard me with seriousness and attention. “In one house I was happy enough to meet an aged priest and two of manly aspect and evidently about 30 years of age.

“I supposed we conversed together for nearly two hours. They asked me many questions and appeared more than half convinced that their progenitors at one period served only one God and that one was the true God.

“During our discourse I remarked to the oldest priest that the time was not far distant when his children would blush when they had to acknowledge that their father was one of the devil’s priests. He instantly hung down his head and remained silent for a length of time.”

In a letter to his father in 1844, Williams wrote: “After what I have said you will scarce know what I mean by saying that Somosomo is an indescribably better place now than it was five years ago.”

“Yet such is the case although amongst the people we can count but one nominal Christian a young man 20 miles distant from the station yet a great, and with deference I would say it to you and my dear friends at home, an inconceivable work has been accomplished, a work which has cost the agonizing prayers, the tears and all but the life’s blood of some who have engaged in it.”