Over the past few weeks, we have been following the life of Jean Elizabeth Brown nee Dods. Her journey from Fiji to the Gilbert and Ellice Islands and how she finally met the love of her life Captain Stanley Branson Brown has been a compelling tale of romance in the South Seas amidst its many challenges.

In the last installment of our Point of Origin series on her life and times, we learned of Ms Dods first meeting with Captain Brown and the two years they spent developing their friendship until he asked for her hand in marriage.

Today we look at the changes, surprises, fun and great happiness they shared in their colourful island life. Having led a very sheltered life and coming from an upbringing where men were a forbidden fruit, being married to one had its fair share of challenges.

She had resigned from her position as secretary to the resident commissioner of the then Gilbert and Ellice Islands and they moved to Betio on their return in 1952. Almost immediately after they returned, Captain Brown was back out to sea.

He would be gone for a week aboard the Tungaru on a voyage taking supplies to the islands and collecting copra. Unfortunately, the house they were to move into was not quite ready and so Mrs Brown had to stay temporarily at another abode not too far from where hers was pending completion.

Only seven years prior, Betio was struggling to recover from the World War II battle for Tarawa.

Military armaments littered the bomb blasted island and the lagoon, and the coconut trees that once crowned the little strip of coral in the middle of the Pacific Ocean were snapped like match sticks – if not completely shaved from the head of the atoll.

Most of the armaments, as well as planes which were downed during the war were still defiantly poking out of the sand and the water. And this was the scene that greeted the couple when they returned from their honeymoon.

A great many Allied and Japanese troops, as well as Korean labourers died there during the war – close to 6000 casualties had resulted from the battle alone. One could say the place was literally soaked in blood.

“The greatest tragedy of all was that of young New Zealand coastwatchers who were executed along with other prisoners of war by the Japanese,” she said. Coastwatchers were military intelligence operatives stationed by the allied forces on remote Pacific Islands during the war to observe enemy movements and rescue their stranded comrades. Their role in the Pacific Ocean theatre and South West Pacific theatre could not be overstated.

According to the late New Zealand writer and amateur historian David Hall, in a section he contributed – entitled The Southern Gilberts Occupied – to The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War, the Japanese overran the Gilberts in September1942.

17 NZ coastwatchers – seven wireless operators and ten soldiers – were taken prisoner and put to the sword in an execution following an American air raid in October of the same year. The Fijian phrase sa tawa na vanua was often used to describe a place that had an eerie spiritual-type presence that appeared to haunt it.

The site of the executions was a stone’s throw away from the house she was staying in. For the first time in her life Mrs Brown said she experienced feelings of real terror.

“Each night I went to bed I was overcome with this terrible feeling of absolute dread.

“I was used to living alone and had no fears, but the first few nights were the most frightening I had ever known.”

The feeling of dread was so strong she would lie rigid in terror. After a few nights she told her Gilbertese house girl about what was happening.

“She told me to change the position of my bed, which I did and I never had the experience again.”

That small change was all it took to stop the dread and even when they moved into their own house she never felt it again – despite the fact that a few skulls had been unearthed when the ground was levelled to lay the foundation.

However, she said life went on as it does. Mrs Brown said she thought she would spend her days living la dolce vita in the warm sunshine, but she was headhunted by a local firm, somewhat comparable to what Morris Headstrom used to be.

“In no time at all I had been snapped up to work in a wholesale office there.

“Stan would go off for two to three weeks at a time collecting copra around the islands and I stayed home and went to work.”

They were two very independent people, used to being on their own, but had chosen to be together.

Mrs Brown said it was lucky he went to out sea and pondered on what could have happened if he was at home for too long.

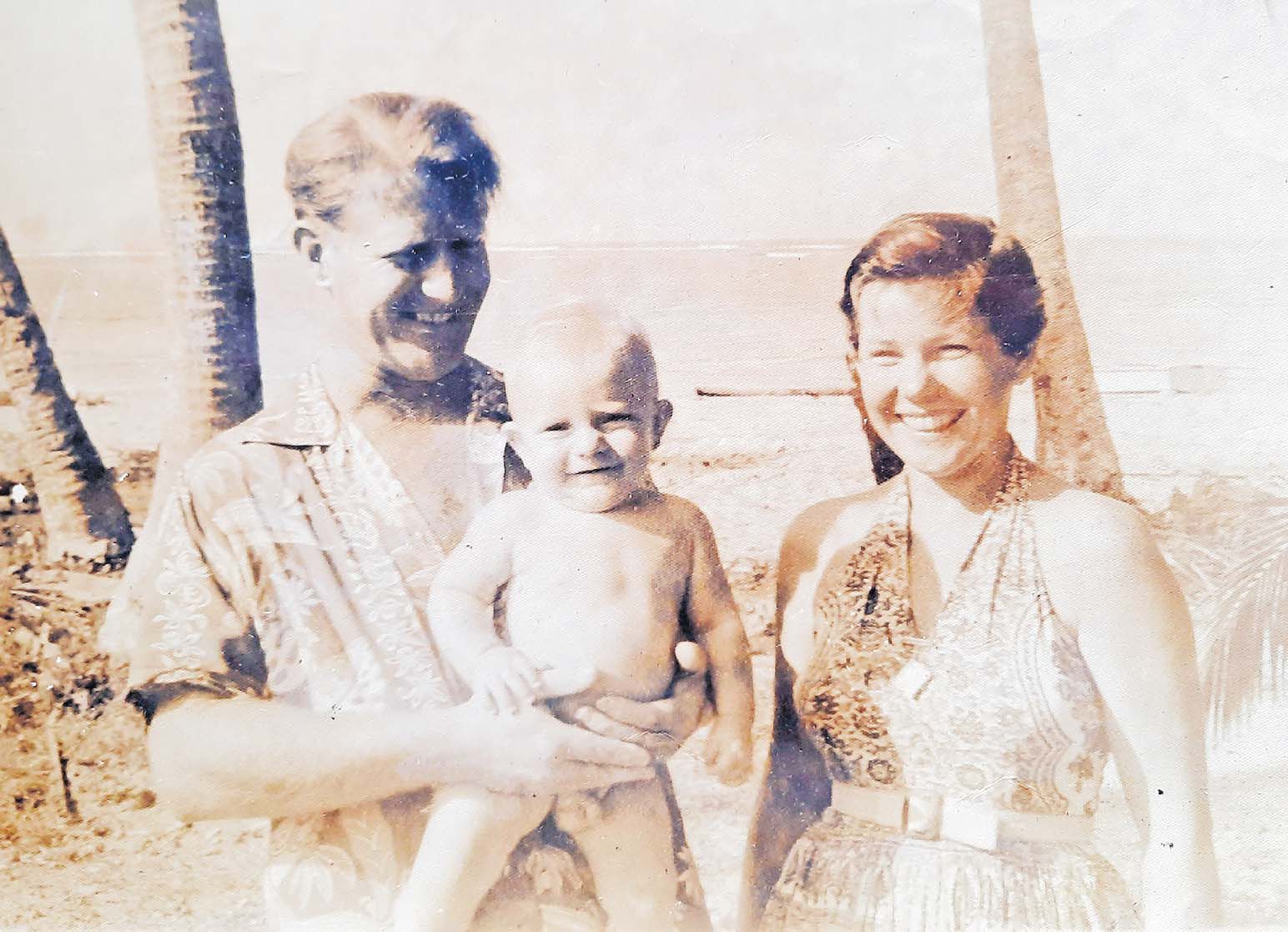

Two years later in 1954 their first child Stanley Jr was born.

Where the other wives of the colonial administrators would get on a ship to Australia, New Zealand or Fiji to give birth because they were not satisfied with the hospital there, Mrs Brown, consistent with the position she had taken on many of the pernickety concerns of the rest of the establishment, decided what was good enough for the Gilbertese was good enough for her.

“All the other women would go to Australia, New Zealand or to Suva to give birth, but I said I was going to have my baby in Tarawa, which I did without any problems.

“There was a hospital there but they thought it wasn’t quite right.”

Captain Brown had been married before and had two young kids.

“He was used to children and he loved his other kids. “When Stanley Jr was about a week old I heard the Gilbertese nurse girl running up and crying out to me ‘the captain, the captain’ and I asked what the matter was.

“Stan had taken his namesake out into the lagoon to give him a saltwater bath to introduce him to the sea.”

The poor Gilbertese nurse girl probably thought the boy would perish that day, but he didn’t.

Their children were everything to them and as their family grew, Captain and Mrs Brown passed on the magic of their own personalities and the rays of sunshine that just seem to emanate from their eyes, their smiles and their laughter.

Not long after Stanley Jr was born, Captain Brown heard whispers that a plot to start a Fijian Navy was afoot.

If you remember from the first part of the series, Captain Brown was the man who started what was today the Republic of Fiji Navy.

He had gone through the war with the Fiji Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and saw active service in the Solomons and the Gilbert and Ellice Islands.

He had been writing letters to the Colonial Government of Fiji for some years, urging that Fiji was ready to have a Navy. So when he heard the rumours, the family packed up and shipped out.

“So we packed up quickly and rushed to Suva to pursue the dream.”

We must remind ourselves that this was the Pacific in 1954.

While the De Havilland Comet was flying the empire routes with the British Overseas Airways Corporation (now British Airways), the Queen Mary was steaming across the Atlantic, and Harold Gatty’s Fiji Airways was just spreading its wings to take flight, trying to get to or from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands was not a glamorous affair.

It is an inconvenience when a flight is delayed by one hour today.

Back then you could wait six months for a boat.

“We decided to return to Suva, on the 50 foot (15m) ketch Kiakia.”

Stanley Jr was six weeks old and again, 1954, there were no disposable diapers, a solution had to be found to get around the water restrictions to wash the dirty nappies.

Mrs Brown said Captain Brown solved this by tying the nappies altogether and trailing them off the Kiakia’s stern like a ships log as they sailed across the Pacific.

How did they fare back in Suva? Find out next week.