In old Fiji, having multiple spouses or polygamy was practised but in very “limited form”. Powerful chiefs had as many wives and concubines as their wealth and influence would support. But the bulk of the people were monogamists. It could be easily said then that high chiefs were an exception to the general concept of sexual restraint.

The Chiefs did not enjoy intrigue with girls of high class only. They could request the company of any woman of humble birth, particularly in the villages of their vasu or of their dependent vanua.

In this, as in many others aspects of indigenous life, the chiefs were above the law. Many of them made a practice of asserting the privileges that their ranks allowed. When a chief called for a low-born woman, whether a maid or wife, she received the summons as if they had been a divine command, however distasteful it might be to her.

“If she hesitated, and the chief condescended so far as to entreat her, sealing his entreaty by sniffing at her hand (rengu), refusal was impossible,” explained anthropologist, Basil Thomson, in The Fijians — A Study of the Decay of Custom.

This kiss of entreaty from a chief was dreaded, especially by unwilling girls.

They sometimes used violence to prevent the nose of their chiefly kisser from touching their hand. For back in the olden days, the Fijian kiss, like that of other races, was a sharp inhalation of breath through the nostrils and not necessarily the smacking of the lips on the skin. The considerable licence was tolerated at every high chief’s house between the chief’s retainers and the female servants of his wives.

These were women taken in war, or good-looking girls from the vassal villages who had enjoyed the short-lived honour of “concubinage” (where a young girl was preserved for marriage to a man). But the wives and daughters and favourites of the chief were untouchable.

The man who dared to interfere with them put his life in great danger. Fijian boys and girls in a village were allowed to associate freely during the daytime. They normally played games such as veibili and sosovi together, but they were kept apart after dark. The girls always slept with their mothers.

Sexual relations

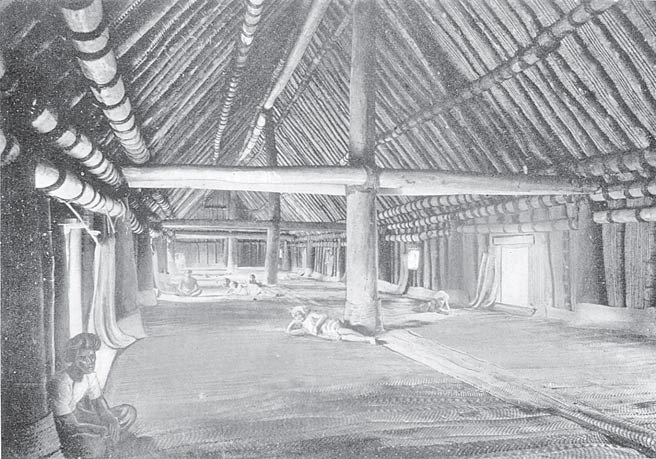

However, for boys, as soon as they reached puberty, at which they were circumcised and wore their malo (plain tree bark cloth worn by men), they were compelled to sleep in the bureni- sa, the village “club-house” in which all unmarried men, village elders and strangers slept every night.

The bure-ni-sa was the biggest structure in the village, asides from the towering temple, burekalou, and the magnificent chiefly residence.

The girls were so carefully watched, if not preserved for their husbands. They retained their virginity until marriage. The young men were always occupied with training, hunting or war.

They neither had the opportunity nor the inclination for sexual intrigue. By sleeping with other men at the bure-ni-sa, it was easier to assemble them to defend the village during any surprise night attacks. “In every community sexual laws were of slow growth.

They were not the expression of a high ethical standard. Primitive races saw no sin in sexual relations,” Thomson noted. Unwritten laws on sexual relationships were designed for public convenience.

They were not the inspiration of a divine lawgiver, but rather the expression of the tribal conscience and to preserve the common good. The Christian seventh commandment was an inscription upon tablets of a law that was initially observed by the Hebrews.

The Fijians had evolved their law from considerations that were from a purely practical standpoint. “Women were chattels,” Thomson said. “A virgin was more marketable than a girl who had adventures; an illegitimate child was a burden upon its mother’s parents.”

Despite this primitive culture of the early Fijians, sexual affairs was an infringement of the Fijian marriage law and each individual woman had her proper partner and place in the community.

Thomson said this maintained the “equilibrium of exchange” of women with the intermarrying tribes and a “just interchange of marriage gifts”.

“That a high moral standard was not the cause of their strict law was shown by the fact that married women in heathen times practised a laxity of morals unknown to them before marriage.”.

Adultery was punished but the women went about their amours discreetly, choosing the times when their husbands were absent on war parties, and reflecting that “what the eye does not see, the heart does not grieve for.”

Secret abortion

Because of liaisons and secret affairs, unwanted pregnancies existed and abortion was sometimes practised. According to Thomson, abortion in those days was limited to women of chiefly or high rank who, for strange reasons, were “not allowed to have children”.

He said when it was known that a lady of rank, who had married into another tribe might bear children, steps were taken to “limit the number of her children”. Every wife had an interest in stopping her rivals from bearing sons who could rise to succeed the chiefly throne.

In this regard, the chief wife had an advantage. She had authority over the other wives.

This enabled her to carry her wishes into effect. Missionary Joseph Waterhouse, celebrated as the missionary who converted Ratu Seru Cakobau into Christianity, mentioned that professional abortionists were sent to “every lady who married out of the tribe”.

They were tasked with the duty to “procure a miscarriage of her mistress”. The Reverend Walter Lawry, who visited Bau in 1847, declared, on the authority of all the resident missionaries, that “the practice was slowly weakened”. But this practice was not observed by the common people.

The abortionist’s knowledge and skills was more or less a secret. They were passed on secretly by the experts known as “marama vuku” (wise woman) to their daughters. All this has now changed with the advancement of the law and medicine.

Thomson said the rapid increase in the practice of abortion was to some extent “the doing of the missionaries”. How was this so? The custom of allowing women and men to sleep separately unless married had a role in maintaining morality and integrity among the old Fijians.

Thomson said with the separation of the sexes at night is no longer required, according to new church teachings, “intrigues with unmarried women increased”.

As this ideal grew, the missionaries convicted the early Fijians with the principle behind the seventh commandment and threatened them with “expulsion from church membership” according to Wesleyan teachings, if found guilty. Many girls who had come to treasure their “curu siga” (attaining a certain level of church membership) and then later found themselves pregnant, started to dread “exposure, expulsion and disgrace”. Abortion became an option.

An illegitimate birth brought shame upon families of every rank unless the father was of high rank. During Thomson’s time, enough of the stern customary law that cast a social stigma upon the mother of an illegitimate child exited slowly.

“There still survives enough of the ethical code that refused to regard the procurement of abortion as a criminal act to warrant women in choosing what is to them the lesser of two evils,” Thomson said. “Moreover, the tendency to the practice of abortion is cumulative.

A girl induces a miscarriage to escape the shame of her first pregnancy. “

To the natural tendency of women who have once miscarried to repeat the accident is added the temptation to undergo, for the second time, an operation that has already been successful.” Fijian women disliked the burden of tending to children born in wedlock.

But to live with the disgrace of bearing an illegitimate child was far worse.

The veil of secrecy

Thomson said some districts were known to be the most accomplished in procuring abortion. “It must be remembered that, since procuring abortion is regarded as a criminal act, the practice is now concealed, not from any sense of shame, but from fear of criminal prosecution,” Thomson said.

He said the practice was veiled in so much secrecy that not only was there few abortions but very few prosecutions took place too. T

he methods of the Fijians were, as in other countries, both toxic and mechanical. Certain herbs, called collectively “wai ni yava” (medicines for causing barrenness), were taken with the intention of preventing conception. The abortives varied with each district and the practitioner, but they generally used leaves, bark or root of herbs, chewed or grated and infused in water. The preparation was naturally more basic, and the doses were “nauseous and copious” than the extracts of m o d e r n medicine.

The village nurses (“wise women”) appeared to know that drugs that irritated the bowel had an indirect effect upon women. Young married women were therefore cautioned against drinking wai vuso (frothy drinks) without medical reasons or advice. This certain class of native medicine were made from the stems of climbing plants.

Their saps often imparted a frothy or soapy infusion, which were taken under various pretexts, but generally as herbal medicine. Foremost among mechanical abortion means was the sau, which was a skewer made of losilosi wood, or a reed. It was used, of course, to pierce the membranes, and in unskilful hands it was a “death-dealing” weapon, Thomson said.

(This article was adapted from The Fijians – A Study of the Decay of Custom by Basil Thomson. Sir Basil was an anthropologist, former commissioner of native lands and stipendiary magistrate of Fiji and travelled extensively through the country during his career.)

History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor.