According to written accounts from Rowland Gouch Michael “Mike” Varley, the first chief executive of the Civil Aviation Authority of Fiji (CAAF), Nadi was selected as an airfield site as it was relatively fl at. “The construction of a small grass air base at Nadi suitable for use by DH-89 Rapide aircraft was completed by March, 1941,” Mr Varley writes.

“However, while Nadi was still under construction, ‘Unit 20’ of the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) consisting of four aircraft arrived in November 1940. It eventually became the number four reconnaissance squadron of the RNZAF in the South Pacifi c area.”

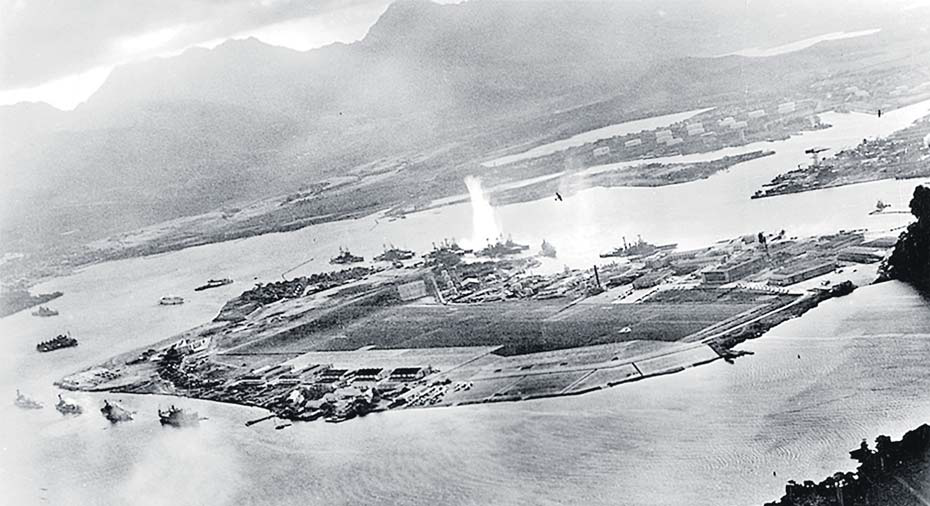

On November 17 1941 the United States asked New Zealand to upgrade the Nadi airfi eld it had established and build on it additional runway, so that “Fiji could be used as a staging point for American aircraft on the South Pacific air-ferry route”. The US wanted the whole project rounded off by April 15 1942. According to war records the attack on Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, just before 8am on Sunday morning of December 7 1941 quickened the project work in Nadi.

The Pearl Harbour bombing was a surprise strike upon the United States and led to the “United States’ formal entry into World War II the next day”.

“Japan intended the attack as a preventive action to keep the United States Pacific Fleet from interfering with its planned military actions in Southeast Asia against overseas territories of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and the United States,” says en.wikipedia.org “Over the course of seven hours there were co-ordinated Japanese attacks on the US-held Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island and on the British Empire in Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong.” Bee Dawson, in the book Laucala Bay notes that the time pressure was intense as the first set of runways had to have 5000 feet of stabilised surface by January 15 1942. After arriving in Fiji on November 30, 1941, the first 400 workmen were billeted in a camp set up in Namaka.

Temporary accommodation was found in Lautoka for 300 men while the rest were put in army bell tents and marquees in Nadi. Tents were three metres by 2.3 metres in size. Within a fortnight a huge campsite was up with 900 local Fijian men and the camp was completed after six weeks. Another contingent arrived on December 4 1941 on the ship Wahina and within a space of a few weeks “1200 labourers of European extraction and roughly 2000 local men” were employed on the project. Of the total, 600 NZ men were armed with American rifles and Browning machine guns. They were trained for emergency operations. The NZ government had to open its prisons to fi nd suitable men to work on the Nadi project.

Nadi was bustling with thousands of servicemen and civilians who did not really understood each other. Nevertheless, they worked side by side despite “vastly differing rates of pay, conditions and privileges”. Philip Snow, the then local magistrate noted the following: “Fijians were drafted in from provinces to carry out strategic construction work in Nadi, where they both overcrowded the villages and had to be fed.”

“When not taking court, I was now having to escort lorries carrying bags of rice and tins of meat to villages where I would dish out portions…” Most equipment needed for the project were sourced from New Zealand while others were obtained locally. In the book Offi cial History of NZ In the Second World War, writer Oliver Gillespie noted the work in Nadi this way: “For months the Namaka area lay under clouds of dust which mounted higher and higher in the hot air and tarnished all green vegetarian for miles around.

“Although a blackout was imposed in Suva after the Japanese entry into the war, such precautions were impossible in the west, where huge air-lights illuminated the landscape as work continued through the night.” On January 6 1942 the fi rst two runways were tested and were found “satisfactory”. “This was a huge relief as just four days later, in the late afternoon of January 10, three Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses arrived from Canton island and landed on the southern half of the strip,” Dawson says.

When three Liberator bomber planes landed two weeks later, the crew remarked that “the runway surface was the best”. It was an immense achievement – small wonder that The Pacific refers to the Fiji aerodrome as “one of New Zealand’s most important achievements in the Pacifi c theatre of war”. “As this cavalcade of the newest American bombers intensifi ed, the New Zealanders could only stare in wonderment.”

By the end of April 1942, the three airstrips were almost completed. Statistics show the project had involved 78,000 cubic yards of earthworks, 500 cubic yards of crushed stones from the Sabeto quarry and 20,000 tons of cement being used to concrete the runways. By May 27 1942, the labourers and equipment were on their way back to New Zealand, leaving behind the RNZAF’s No.2 Aerodrome Construction Squadron to clean up.

Everything was satisfactorily completed by the time the main body of US forces began arriving in June. “At 0600 hours on 18 July 1942, the United States Army took over command and responsibility for the defence of Fiji,” says Dawson. From this point until December 19 1946, Nadi operated as a USAAF base with three airfi elds. The main Nadi fi eld built by NZ in 1939 to 1940, and rebuilt and extended in 1941-42 was used by bomber squadrons and aircraft in transit.

The second fighter strip at Narewa was also known as the Griffi ths strip, named after Eric Griffi ths, an RNZAF pilot who died when piloting an Airacobra fi ghter in February 1942. The third strip, Martintar, was the US Naval Air Station. All three fields were connected by the taxiway that had been built by the RNZAF’s No.2 Aerodrome Construction Squadron. Only the Nadi strip was concreted. The others were only stabilised by “packed gravel and grass strips overlaid with steel matting”.

Construction of the Martintar airstrip displaced families who lived in the area. One of them was the Kennedy family, whose homestead was at today’s Mount Saint Mary Parish premises. The family had moved there from Ba. Tourism icon and operator Bob Kennedy said during his last interview with this newspaper in September 2020 that his family home in Cawa, an area now generally called Martinar (after his father’s name Martin) was taken over in 1942 for use by the US military.

The Kennedy land was also used to build runways, aircraft dispersals, naval airstrip as ammunition dumps. In his book Harold’s Getty’s Legacy, Mr Kennedy said he was very young at the time. “My brother and I, two cousins, mother and our maid were evacuated to New Zealand,” he says.

“My father who was a works foreman for the RNZAF in Nadi was moved to Laucala Bay. In June 1943, he was on a Catalina flying boat which crashed on his way to join us in NZ. There were no survivors.”

The Kennedy returned to their home in 1945 when the war was over and the USAAF had moved on. Across the family home at Cawa Rd, Bob himself began school at Miss Brewer Kindergarten, before moving on to St Thomas School, and then Suva Grammar School.

He finished his tertiary years in Queensland, Australia. Some believe World War II brought about a modernisation process in its five years much more extensively than many years of colonialism since 1874. According to a study report titled The Material Remains of World War II in Viti Levu, author Ja Bennett said the use of Fiji as a forward base brought in “many troops and vast quantities of supplies”.

“The facilities and infrastructure put in to accommodate these people brought forth many modem amenities. Despite the lack of a violent clash on the islands, the global confl ict greatly impacted the islands and ultimately developed many aspects of modem life in Fiji.”

Next Week: Part 3: The rise of Nausori’s boggy airfi eld