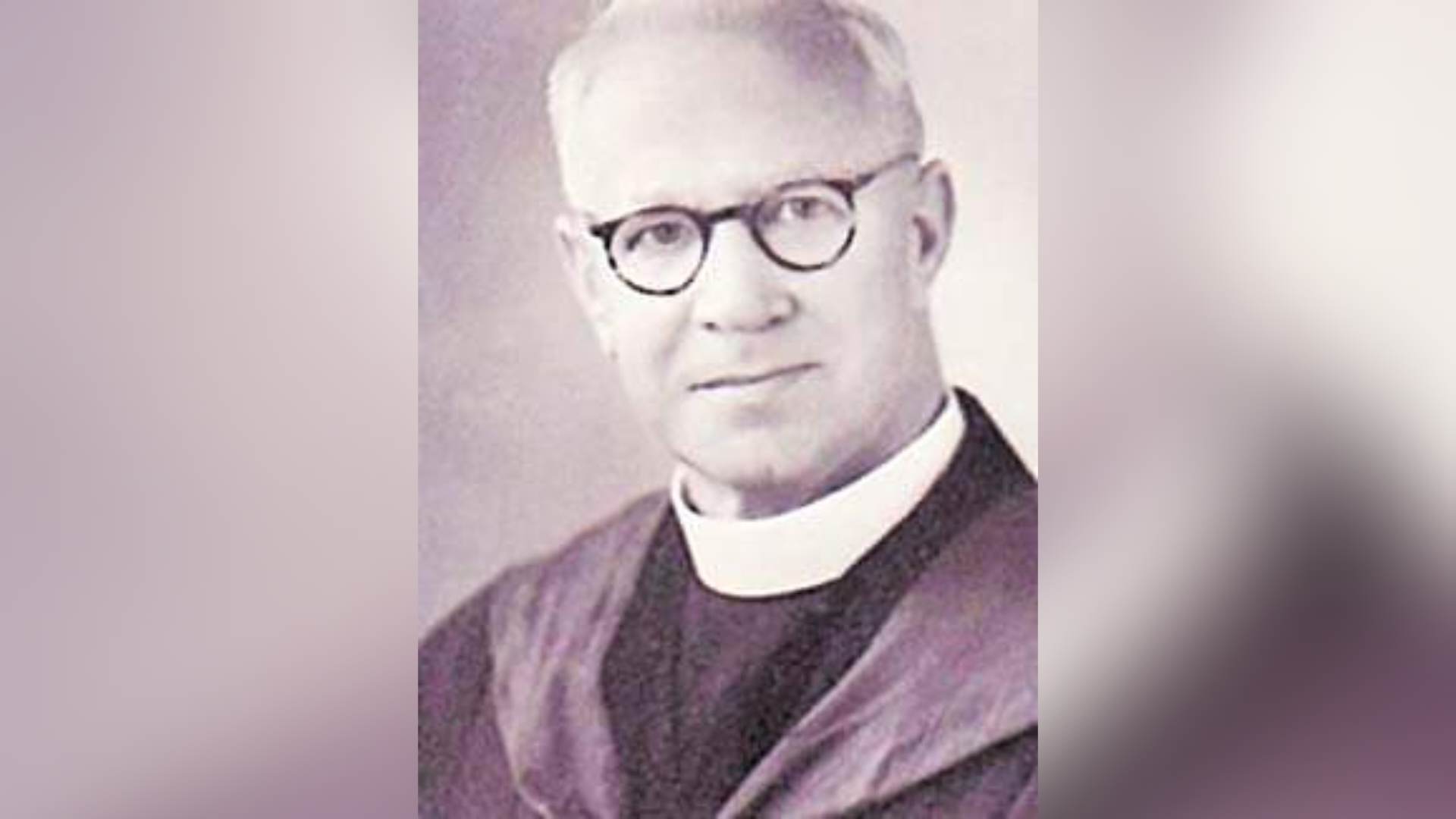

M ANY names have been associated with the development of the Methodist Church in Fiji’s Indo-Fijian Mission in the late 1800s. One of them is John Wear Burton.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography noted that he was born on March 8, 1875, 148 years ago in Lazenby, Yorkshire, England.

He was the son of Robert Burton and Maria Bell. To benefit his mother’s health, in 1883, the family migrated to New Zealand, settling at Masterton.

At the age of 12, Burton left school and began work as a fleece-picker at a retail store before he started apprentice work at his father’s wheelwright trade.

Influenced by a family missionary tradition and local church life, Burton became a lay preacher at 17.

In 1895, he began his theological training in Auckland, was appointed as a probationer two years later, studied part time for matriculation then enrolled for university work at Canterbury in NZ.

“In 1879 he attended the inaugural meeting in Melbourne of the Student Christian Movement of Australia and New Zealand,” the ADB stated.

There he joined the Student Volunteer Movement whose members were pledged to be missionaries.

“After ordination in 1901 he was shifted to Christchurch but was soon asked to take charge of Indian missionary work in Fiji.

“On the day of departure, April 24, 1902, he married Florence Mildred Hadfield.”

When Burton began work in Fiji, he was shocked to see the living conditions of the indentured Indian labourers on the sugar estates and exposed the abuses in his book, Fiji of Today, which was regarded an influential and controversial book.

“It was regarded as a pioneer work by Rev. C. F. Andrews in India, whose later agitation helped to terminate the indenture system in 1920.”

A book titled, ‘Mission Divided’, a specific chapter ‘Foundations for an IndoFijian Methodist Church in Fiji’ written by Kirstie Close-Barry talks about Burton’s involvement in the mission.

Close-Barry wrote that the board relied on fresh ministers after their efforts were unsuccessful to bring missionaries from India into the Pacific.

“One of these was John Wear Burton, despite having no prior experience in India he was selected to work exclusively in the Indo-Fijian community.

“He gathered up his belongings and got on board the boat, full of enthusiasm and trepidation at the thought of leaving New Zealand for the adventure that lay ahead.

“But Burton received a warning from the outspoken ship’s captain during his passage in 1902: ‘The Indians have their own religion and want none of yours.”

The chapter noted how Burton was not affected by this statement and after a short time in Fiji he declared himself as the leader of the mission’s IndoFijian work. Burton even learnt Urdu with a man name Daniel Nizam-ul-din who was a worker at the sugar plantation.

“They had met when Nizam-ul-din was serving time in prison, and Burton transferred Nizam-uldin’s indenture to his own name for £16, engaging in the indenture system in the process of trying to secure his own language tutor.

“He also enlisted Nizam-ul-din’s help to recruit more converts to Methodism.”

With Reverend Arthur J Small, they closely worked to establish the infrastructure for the Indian branch.

During the year 1902, the two travelled along the shoddy road to Baker’s hill in Nausori to select a suitable site for the Indo-Fijian mission house.

“Small and Burton walked around the existing site, plotting where additional buildings might be placed, and decided to position the Indo-Fijian activities across the creek from the existing Fijian compound.

“In 1909, Burton and Small named the block that they had dedicated for the Indo-Fijian mission ‘Dilkusha’, after a colony in Lucknow, India.

“The name means ‘my heart is happy’ in Hindi. Through the processes of design and naming, there were sites of inclusion and exclusion constructed on the basis of race within this Methodist space.”

Close-Barry said when the mission structure was established through documentations, deeds and efforts towards the work of evangelism, Burton sought for financial support from Australians with a deep sense of urgency. She wrote how he depicted Indo-Fijians as a threat to the Christian Fijian in public meetings.

“He argued that if missionaries did not make a special effort to convert the Indo-Fijian community, ‘the crescent of Mohamet’ would ‘displace the cross of Christ in the Pacific’.

“Burton’s ideas about ‘native churches’ and the ‘three selves’ church concept had been influential in the mission field. He left Fiji in 1909, but his influence over mission activities only grew.”

Close-Barry wrote that in the years after Burton left Fiji, he continued to argue that the Indo-Fijian mission should be at the centre of the mission’s activities, despite limited evangelical success in the field.

“He believed that the distinctions between Fijian and Indo-Fijian cultures were permanent; he was convinced that they sat at two different points on the spectrum of social progress and could not easily co-exist.”

The ADB revealed that due to family illness Burton was forced to return to New Zealand and after three years in New Plymouth he was invited to be secretary in Victoria, for overseas missions.

“At the University of Melbourne he continued his interrupted studies. In 1918-20, as an honorary major with the Young Men’s Christian Association, he assisted with the demobilization of Australian troops in London, where he was converted to pacifism.

“Returning to Victoria, he indicated his growing interest in Christian unity, sponsoring United Mission Study Schools and helping to initiate the National Missionary Council, of which he was chairman for eleven years.”

According to an article in the Journal of New Zealand and Pacific Studies, during Burton’s role as General Secretary of the Australasian Methodist Missionary Society in the 1920s and 1930s, he would travel each winter to one of the mission field in the South Pacific. There he would inspect the mission’s activities and encourage and advise accordingly.

“Accompanying him was his camera; Burton had long been an enthusiastic photographer and following his 1924 visit to Fiji he created two albums of his photographs, one illustrating the indigenous Fijian mission, the other the Indian mission.”