Back in the 1800s, when there were no hospitals and nurses, childbirth in a village was looked after by the native midwife, called yalewa vuku, literally translated as wise woman.

The yalewa vuku was the ancient version of today’s “jack of all trades”. She was both the village doctor and nurse. She was also the pharmacist and was believed to possess supernatural powers.

Her medicines were sometimes a secret and any treatment of women’s ailments was done away from the presence of man.

The role often became family property. It was handed down from mother to daughter after years of close outdoor trainings and instructions. During childbirth the yalewa vuku was not only the midwife but the consultant gynaecologist. None but closest female relations of a labouring woman were admitted to be around when a mother was in her final moments of pregnancy.

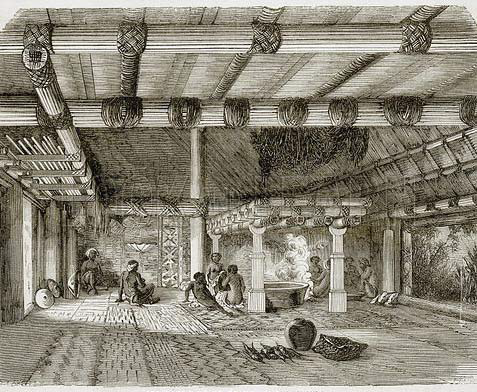

When labour pains started to afflict her, she often assumed a squatting position. But during childbirth she was laid back, with two women supporting her shoulders, while the midwife did her job and gave orders.

“From a physiological point of view this is a disadvantageous position, but it appears to be adopted by chance rather than design, it being a natural posture for a people who both sleep and sit on a matted floor,” anthropologist, Basil Thomson, noted in The Fijians – A Study of The Decay of Custom.

Midwives from different parts of Fiji differed over the practice of severing the umbilical cord, the lifeline used by the baby and her mother during the nine months of pregnancy.

Some midwives knew that the cord pulsated, but they did not understand the reason, for the early Fijians did not learn about the circulation of the blood in school nor did the midwife herself, Thomson said.

The first cry The midwives generally waited until the neonate (newly born child) drew its first breath or belched out its first shrieking cry.

If the baby did not cry the midwife would compress the cord between her finger and thumb.

This was to squeeze the blood towards the child. Sometimes the midwife would rattle a bunch of kitu (water pitcher) near its new pair of ears so as to awaken it from its watery slumber.

Neither artificial respiration nor a dash of cold water was used. The cord was measured from the navel to the knee, and cut using a “knife” made from sharp mussel shells or bamboo slits.

Nowadays, a pair of scissors is used by doctors in a sterile hospital environment that is conducive to childbirth and safe for both a mum and her bundle of joy. After severing the umbilical cord called vicovico, the fetal strand is wrapped in a shred of plain bark-cloth or masi.

The blood that seeped from the cord was absorbed by the cloth. This was changed occasionally. The navel was soothed occasionally using coconut oil.

One of the first celebrations of life in the village was done when the baby’s umbilical cord fell off the navel.

The fallen cord was then taken and buried somewhere significant to enhance the baby’s connection with the land, customs and traditions.

This place of burial was often marked by planting in a tree to mark the child’s growth.

For those in the islands, coconut was the tree of choice.

Cutting the umbilical cord

Once the child cried and the cord was cut, an attendant washed the newborn in cold water.

Thomson said in his book that retention of the placenta was often dreaded by Fijian women but the midwives said that it was as rare as it was dangerous.

Among some highland tribes, the midwives often used the hand to extract the placenta. In cases where a drink of cold water did not work, herbal infusions were administered to the new mother, and herbal poultices were sometimes applied externally. “… but the safe expedient of compressing the uterus by placing the hand on the abdomen is unknown to Fijian midwives—a surprising fact in a nation of masseuses,” Thomson said.

He said the occasional retention of portions of the membranes appeared to puzzle Fijian midwives.

Fijian mothers sometimes die from retained placenta or kubekube (cleavings), the word they called the afterbirth.

Thomson said, after the conclusion of the third stage of labour some midwives of the inland tribes inserted the hand as far as the baini yate (fence of the liver) or a part of the birth canal called the tuvu ni gone, in an attempt to clear out all the clots.

Others used the practice of raising the mother in a sitting position to facilitate their discharge by gravitation.

The herbal concoction, wai-ni-lutu-vata, was sometimes taken by the mum during her later months of pregnancy, to allow a normal delivery and for the easy expulsion of the afterbirth.

Women from the highland often left the house within a week to carry on their household chores.

They also continued to do heavy chores during the advanced stages of pregnancy. Some would venture out to the bush in the morning and return in the afternoon “with a load of fi rewood on her back and a new-born child in her arms”. Among women of the high class, the story was typically different.

Carrying the baby

The women were usually kept in the house for a full month after birth. Some women observed the bogi drau (hundred nights).

During this three-month period, the mother was required to abstain from all physically strenuous work that could make her sick or tadoka. Accidents at childbirth were rare with Fijian women, Thomson said.

However, he said, when abnormal births occurred they were regarded as being the fruit of an adulterous connection or the works of witchcraft. If the child died, the death was never blamed on the midwife.

The mother was referred to as mama or “light”, if the birth was successful. In certain parts of western Viti Levu, heavily pregnant women were confined to the outdoors and things used during childbirth was burned. A temporary hut was erected at a considerable distance from the village, and the pregnant woman was required to deliver her baby there. No preparation was made beyond “taking a rough creel, padded with dried grass, for the reception of the new-born infant”.

There was no midwife, and the women did all that was necessary for herself.

The key to these primitive customs was “the belief in witchcraft”.

Back on those days, to inflict death and disease on a victim, the most effective tools used by witchdoctors were the excreta discharged from the human body, the more repugnant the better.

It was feared that if the woman was attended to during her confinement, even the slightest bloodstain on a blade of grass could be used by a malicious person to cause her death.

Therefore, she used no mats. Mats were too precious to be later burned, and every mat she used would be a weapon in the hands of her enemies.

So she would bring her child into the world unaided. The hut where she gave birth was burned down before she returned to the village.

“Now, mark how superstition works for sanitation. Whereas the child of the coast is brought into the world in a stuffy hut, and swaddled in dirty bark-cloth, reeking with impurities, the inland baby and its mother are guarded against infection by a law of cleanliness more rigid than any that the Mosaic code enjoined,” Thomson said.

The role of wet nurses

It is peculiar to note that the Fijian child began his or her life with a dose of medicine. Soon after delivery, the baby was cleaned in cold water.

A little bit of juice of the candle-nuttree (Aleurites triloba) or any other medicine for children was put into its mouth to make it vomit.

Then a ripe coconut, or in some places a plantain or vudi, was prepared and chewed into a porridge-like pulp.

This was then put in coconutshell cup and a piece of bark-cloth, shaped like a nipple, was dipped inside and given to the child to suck. That was the native baby’s first taste of food. The mother’s first milk straight after birth was considered unwholesome.

It was expressed and disposed of. On the first day, or the first three days in the case of a chief’s child, the newborn was put to the breasts of a “wet nurse”, a woman whose role was to breastfed the child instead of the new mother.

Wet nurses were employed full-time if the mother died or was unable to nurse the child herself. The Fijian wet nurse was strictly forbidden to bathe or fish in salt water.

When the mother’s breasts were full, after a day or two of eating, her child was given to her to suckle.

The children of chiefs were often suckled and minded by more than one woman.

According to Thomson, the missionaries tried to discourage the employment of wet nurses, probably because her own child was likely to suffer from neglect.

One or two girls each from the wife’s and the husband’s family were tasked to feed and tend the new mother.

Also, the two grandmothers of the child, if living, also helped to nurse and teach the new mother about the ropes of motherhood.

Chiefly children or the eldest child to be born to a couple, were often carried by elderly women for four nights.

They wrapped bark cloth around the baby, and passed the baby around while kissing it and singing popular lullaby songs.

They also took turns to bless the baby by saying positive words.

The birth of a child was a time of fun and gaiety. The woman who carried the newborn while its cord fell off was given a punishment of sorts called ore.

She was required to prepare food for the tending women. But at the tenth day they all left the new mum to the care of her husband. A feast was also prepared before all women went back to their homes.

During the first ten days the mother was confined to a diet that included green vegetables and fresh root crops. She was forbidden to eat what was called ka damu (red things, i.e. fish, crabs, meat or broths made therefrom).

Instead, she was fed taro or bread-fruit puddings, taro and greens. At the end of ten days the new mum was expected to continue with some of her housework.

If she could not command the services of her relations to enable her to lay up for the bogi drau (hundred nights), she resumed all her ordinary outdoor work except going out to sea. Indigenous Fijians believed the sea was bad for mum and baby.

If the mother wet her leg with saltwater at any spot above the calf, her milk would be spoiled. (This article was adapted from the book The Fijians – A Study Of The Decay Of Custom by Basil Thomson)

History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor