Last week, we traced Cakobau’s war club and found that it had originally belonged to Rokomoutu who called it the Sigalavalava. We then followed how the war club was gifted to Vueti who became the first Roko Tui Bau, Vuetiverata. Vueti was Rokomoutu’s sister, Buisavulu’s grandson, through Vula her son. Cakobau was a direct descendent of this lineage and wrested the war club after he conquered Bau in 1837. It needs to be noted that this war involved groupings including that of the Roko Tui Bau (Nabaubau) who were pitted against Cakobau.

When Cakobau wrested that historic war club, the event was both historic as well as symbolic. In fact, the symbolism is underplayed even though it has much more significance within the traditional context which gave it meaning. Cakobau was not only establishing authority over the institution of priest-king (Roko Tui), but he was attempting to finish that power struggle for all time. Governor Gordon would later replace these Roko Tuis with Christian missionaries as the old mana had to be replaced with a new one. The chiefly institution had to have divine concurrence.

That war club that once belonged to Rokomoutu and the first Roko Tui Bau, Vuetiverata, now belonged to Cakobau through whom it became the Mace of Fiji’s parliament. After Speight’s goons tried to destroy it in 2000, a concerned quick-thinking policeman whisked it away and after some time, when told of its historical significance, handed it over to former Secretary to Parliament, Mary Chapman, for safe keeping. I am also told that even though it was returned to Parliament, the Mace that sits in Fiji’s Parliament now is not the original. This, I leave for reporters to verify. Let’s move to this week’s article.

I had earlier stated that there were two types of jockeying “white” interests at play in the lead up to and during cession. Let’s unpack that further here. In order to understand the thinking, presence and motivations of the white man in Fiji, we need to delve into the history of commercial enterprise in Fiji.

Commerce in pre-cession Fiji

The European arrived in Fiji with “startling suddenness” (Thompson, 1908, p.12) at the beginning of the 19th Century. Records loosely classify these pioneers as beachcombers, traders, missionaries, planters, etc. The demarcations, however, are not as stark and clear. These classifications are significant “because the nature and extent of the white man’s influence depended on the relationship which he established with Fijians; and this, in turn, was governed by the ‘occupational category’ to which he belonged” (France, 1969, p.20).

The first white men were shipwreck survivors or beachcombers. One of these, a guy named Oliver Slater, “discovered” sandalwood and reported it back in Port Jackson (now Sydney Harbour) in Australia because it was already known as a sought-after trade commodity in the China circuit. A rush then flowed to Bua where the valuable wood was found in natural abundance. Over the first decade of the 1800s white men began to live among Fijians in various capacities.

The musket was introduced to Fiji by these men. The most notable of them was Charlie Savage who helped Naulivou (and later Cakobau) elevate Bau to a preeminent position in the evolving power structure in Fiji. France (1969, p.23) says that “those chiefs who had already established themselves in positions of power attracted white men to support them and so consolidated their influence”. This tends to show that power attracted the muskets, clearly highlighting the motivations of those early adventurers.

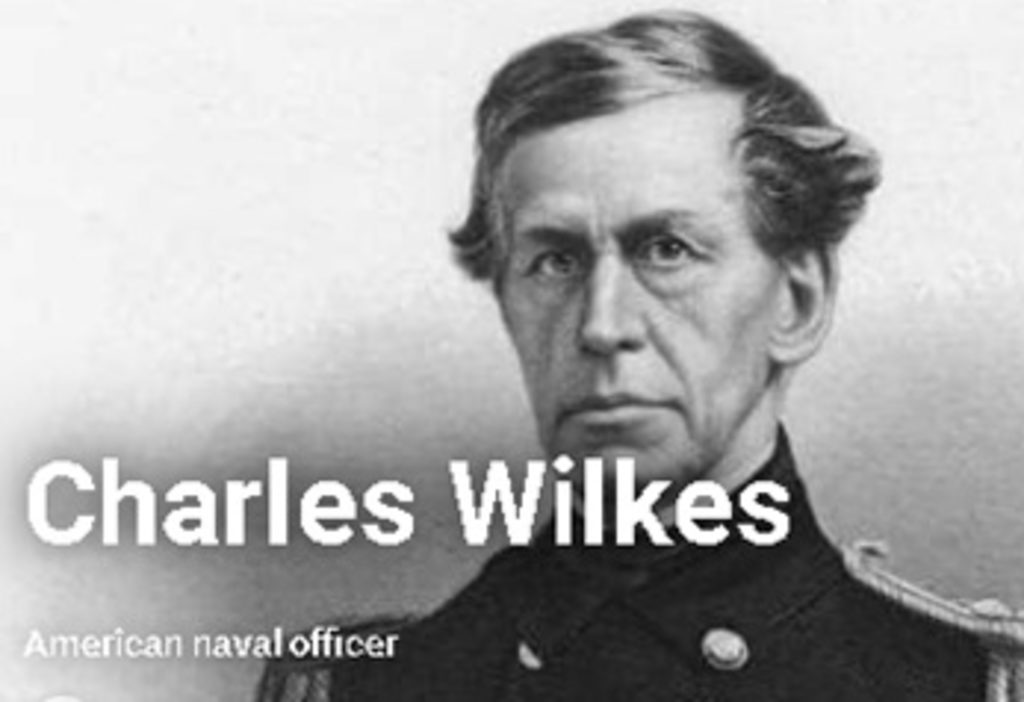

It is interesting to note that after the novelty of a new “type” of people wore off, the white man became an ornament or a sign of prestige for the chief who they attached themselves to. They became accepted as the skills that they possessed made them highly useful domestic servants — mending muskets and/or boats, carpentry, court jester, etc. These beachcombers moved in and made themselves valuable through their skills. They blended into the landscape and “became almost indistinguishable from Fijians in appearance and conduct” (Wilkes, 1845, p.68).

The beachcombers, however, were selective on what they accepted when living with Fijians. They did not participate in cannibalistic rituals citing their own god did not permit this. In doing this, they created a lasting enemy among the pagan priests who would ultimately find their power wane in front of the white man’s god. The beachcombers set this change in motion way ahead of the missionaries. More importantly for the theme being developed here, the beachcombers, as interpreters, paved the way for trade with the native Fijians. The path was thus, beaten for the traders, missionaries and planters who were to follow in quick succession.

Sandalwood trade

After Oliver Slater reported sandalwood back in Port Jackson, ships began arriving in Bua looking for profits. At first, they dealt only with known chiefs because chiefly domains were not clearly demarcated and there was constant danger from hostile parties. France (1969, p.25) writes that, “at first it was the practice to secure the permission of the local chief and send parties of the crew to cut the wood; but, as the trade developed, it became the custom to buy the wood from the chief, who then sent out a party of his people to do the cutting”. These cutters often encountered hostility and attacks from neighbouring tribes. Thus, it was not uncommon for chiefs to ask for muskets as payment in order to protect the trade from these hostiles.

It is important to note that the impact of this early trade in sandalwood was restricted to a small area in the west coast of Vanua Levu. Commoners were given glass beads and iron tools while chiefs enjoyed military assistance. Selected chiefs who could be “trusted” found temporary prosperity and social prestige as the “leading traders” from the Fijian side. The Tui Bua, for instance, was gifted a wooden house by merchants from Sydney. This was said to be the first wooden house in Fiji as architecture involved primitive houses at the time. This trade, no matter how confined, revolutionised the material culture of the Fijians involved (Derrick, 1957). The next focus of interest with a wider geographical outreach was beche-de-mer. Commercial trade was on its way in Fiji.

Beche-de-mer

We saw earlier how the beche-de-mer trade was linked to power struggles between Cakobau and his rivals (FT 13/09/2025). The significance of the link between material wealth and power was understood very early by Cakobau. Coming back to our focus on commerce and its impacts, we find that the beche-de-mer trade had a wider impact because this marine commodity was spread throughout the country. Here again, the trade began through the chiefs, but over time, it spread to direct contacts between commoners and traders. This is how it was organised.

Traders initially contracted chiefs to supply a quantity of beche-de-mer and build drying sheds to continue with the arrangement. Some traders were able to “corner” large areas through these chiefs. This allowed them exclusive access to trade in those areas. Captain Eaglestone was a leading trader who highlighted this aspect of the trade when he wrote in his journal, “With the chiefs under my control, as also the coast, I feared no ship building a house … without my consent to do so” (Eaglestone, p.43 in Vance, 1969, p.26).

It is interesting that as this trade spread, the centrality of chiefs in it waned. People began to travel great distances with their families and set up temporary shelters in areas they were not a part of, in order to collect beche-de-mer and transact directly with traders for payment. In this new arrangement, even chiefs had to wait in line to sell their beche-de-mer. In one instance, a Macuata chief was so incensed because he had to wait that he beat up rival fishermen and confiscated their catch (Eaglestone, pp.423-425 in Vance, 1969, p.26).

It is important to note that prior to the onset of the beche-de-mer trade, the chiefs had in their control the sources of all desired material possessions. These goods were now directly made available by traders to anyone who brought a basket of fish, firewood, etc. to the beche-de-mer stations along the coast. In return, anyone could now become the owner of trade goods like axes, tomahawks, knives, etc. including muskets, pistols and powder.

We will develop this further next week. Till then, a Most Merry Christmas to all of you. Sa moce toka mada valekaleka.

Dr. SUBHASH APPANNA is a senior USP academic who has been writing regularly on issues of historical and national significance. The views expressed here are his alone and not necessarily shared by this newspaper or his employers subhash.appana@usp.ac.fj

Captain Charles Wilkes toured and wrote about the South Seas.

Pictured: SUPPLIED

Sir Basil Thompson joined the Colonial Office as a cadet in 1884.

Picture: SUPPLIED