The amazing journey of Columban missionary Father Frank Hoare continues. Last week, we looked at how he spent the early 1980s building small Christian communities, training more than 80 lay leaders, and introducing the Hindi mass and annual dharm-sammelan gatherings for Indo-Fijian Catholics across Fiji. Now, towards the end of 1981, Fr Hoare supervises a unique pastoral experiment aimed at reducing ethnic prejudice in Fiji. We begin on November 3, when two Fijian seminarians, Vito Buatava and Rafaele Qalovi, undertake four months of intensive Fiji-Hindi study before living with Indo-Fijian families in Naleba, Vanua Levu.

THE experience, according to Fr Hoare, offered both cultural immersion and personal transformation.

“In the early 1980s I tried a social experiment,” Fr Hoare said. “Could ethnic prejudice be diminished through an experience of living in another community?

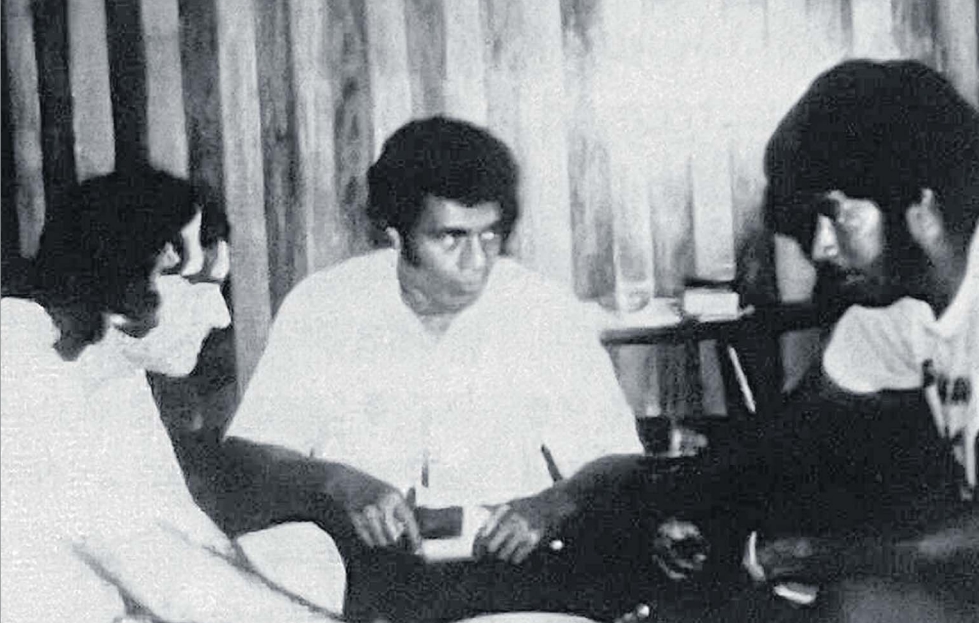

“Mrs Tara Nair was teaching Hindi to the two Fijian seminarians.”

Some of Fr Hoare’s friends couldn’t see any point in what he was doing, and he felt hurt when one said, “heh! your hands have the stink of curry about them”.

He was encouraged though by the welcome he received from the family.

“Don’t be shy. This is your house,” he was told.”

Living with an Indo-Fijian family, he adapted to new foods, customs, and community rhythms. While some acquaintances questioned his efforts, the hospitality of his host family reassured him.

He participated in weddings, festivals, cane-cutting, and prayer meetings, quickly learning Hindi hymns and witnessing the family’s devotion.

Fr Hoare said the experience challenged his preconceptions and deepened his appreciation for Indo-Fijian culture.

“A part of my life that was in darkness is now lit with the light of Christ.”

Confronting long-held fears

By the 28th, Rafaele Qalovi admitted to entering Naleba with significant apprehension, shaped by stories of Indo-Fijians as “quick-tempered” and dangerous.

The isolation of the settlement intensified his unease.

“I was afraid that I would be murdered,” said Rafaele, glancing at the group of Fijian villagers, after drinking a bowl of yaqona.

“The villagers nodded with sympathetic understanding.

“Well, you know what I mean,” he continued, “Since I was a boy, I had been hearing that Indians are dangerously quick-tempered and would use their sugarcane knives to murder when angered.

“When I got into the van that was to bring me to Naleba, I was sweating. ‘It’s very hot,’ I said, but really it wasn’t the sun that caused the sweat. It was the fear.”

However, by joining daily household work, from planting yams to cutting sugarcane under intense heat, he built rapport with his hosts.

Conversations over yaqona and shared labour gradually replaced fear with understanding.

He later observed that political divisions in Fiji reinforced ethnic barriers and called for more initiatives to encourage mutual appreciation.

Encounters with other faiths

As part of the program, Fr Hoare introduced the seminarians to Hinduism and Islam.

Earlier experiences had included open interfaith exchanges, but a visit to the Labasa mosque this time brought a less welcoming reception.

The new maulvi, trained in Pakistan, urged conversion to Islam and expressed strong condemnation of Hinduism.

Disturbed by the remarks, Fr Hoare ended the meeting and left with the seminarians, noting the contrast to previous interfaith dialogue.

The roots of fear

Months after his placement, one seminarian revealed that his initial fear of sleeping in an Indo-Fijian home stemmed partly from childhood trauma involving an abusive father.

It was December 14 and the experience in Naleba had triggered those memories.

“I was appalled.

“But I wouldn’t put you with someone who would harm you.” I told him, “Did you hear people in the village say not to trust Indians because they would chop you?”

“Yes,” he said, “I did.”

“We talked about racial prejudice and how it poisons relationships between people,” Fr Hoare shared.

“He went back to the Indo-Fijian family the next day. He gradually got used to being there.

“The family was very good to him and he got on very well with them.”

Through guided reflection and prayer, he began to address both the racial prejudice he had absorbed and the personal wounds he carried.

According to Fr Hoare, the program not only challenged stereotypes but also opened the way for personal healing.

n In next week’s edition, the story moves into the events of 1982 as Fr Hoare’s itinerant apostolate continued to shape Catholic life among Fiji’s Indo-Fijian communities.