In recent weeks, churches across Fiji have wrapped up their annual conferences, conventions, and AGMs, the kind of gatherings we covered where communities come together to plan, reflect, and decide on the year ahead.

This time, in 1982, we explore how Columban priest Fr Frank Hoare witnessed and engaged with these gatherings, offering insights into leadership, community, and the ways faith can help bridge cultural divides.

Youthful enthusiasm meets tradition

It was 22 February 1982 in Naleba when the parish gathered for its Annual General Meeting.

Fr Frank Hoare remembered the energy in the room as a group of young teachers took their seats, brimming with ideas.

“They had just come out of a lay leadership course,” he said.

“They were convinced that the parish needed fresh direction.”

When one of them stood to nominate his friend for president, the hall erupted.

Older committee members had held the same positions for years, and now their leadership was being challenged.

“How can a young man challenge his elder?” voices shouted. Others added, “And he’s not even a born Catholic, only four years a convert!”

The incumbent stayed silent, but his supporters’ protests filled the room. Eventually, the nomination was withdrawn, and the old committee was re-elected.

“The clash of cultures was right there in front of me.

“The young men wanted progress. But tradition and respect for age were stronger.

“It was a lesson in patience and understanding.”

The need for an intermediary

By march Fr Hoare observed the subtle ways culture shaped communication.

At a church committee meeting, he noticed tension rising as some Indo-Fijian members pressed Fr Theo with difficult questions.

“He said nothing.

“Just sat there, silent. But I noticed the toes of his feet wiggling, you could see the frustration.”

A young lay leader, who had been supporting the priest quietly, intervened.

“Fr Theo will think about that question and give you an answer later,” he said calmly.

The room relaxed instantly.

“It was a small thing, but it kept peace.

“It reminded me that in both Fijian and Indo-Fijian culture, a trusted intermediary can make all the difference.”

Easter vigil at Raviravi

The Easter celebration on April 7 at Raviravi parish was unlike anything Fr Hoare had seen.

The vigil began at 11pm in a shed behind the church and went on until dawn.

“More than a hundred people were there.

“Indo-Fijians, iTaukei, Christians and Hindus, all together, sharing prayer and song.”

They read nine scripture passages slowly, with slides to guide the reflection.

After the story of the Israelites’ freedom from Egypt, everyone wrote down their burdens, sickness, sin, worries and placed them in the bonfire. From that fire, the Paschal candle was lit, and from it, each person lit their own candle.

“The rising sun came just as we began Mass.

“You could feel the darkness of the night lifting, not just outside, but in the hearts of those present. Everyone understood that this was a moment of light and hope.”

Election fears

By July 10, election fever was high, and fear was thick in the communities.

Fr Hoare recalled talking to an Indo-Fijian man who shared a disturbing story about his ancestors.

“One of the early transport ships ran aground on Nasilai Reef,” the man said.

“Some of the people were eaten by the local Fijians. They were cannibals then.”

Fr Hoare was shocked. “I knew that in fact many had been rescued by villagers who risked their lives to save them,” he said.

“It made me realise, how stories can be distorted by fear, time, and conflict.

“People remember feelings more than facts. And those stories shape how communities see one another.”

Games without losers

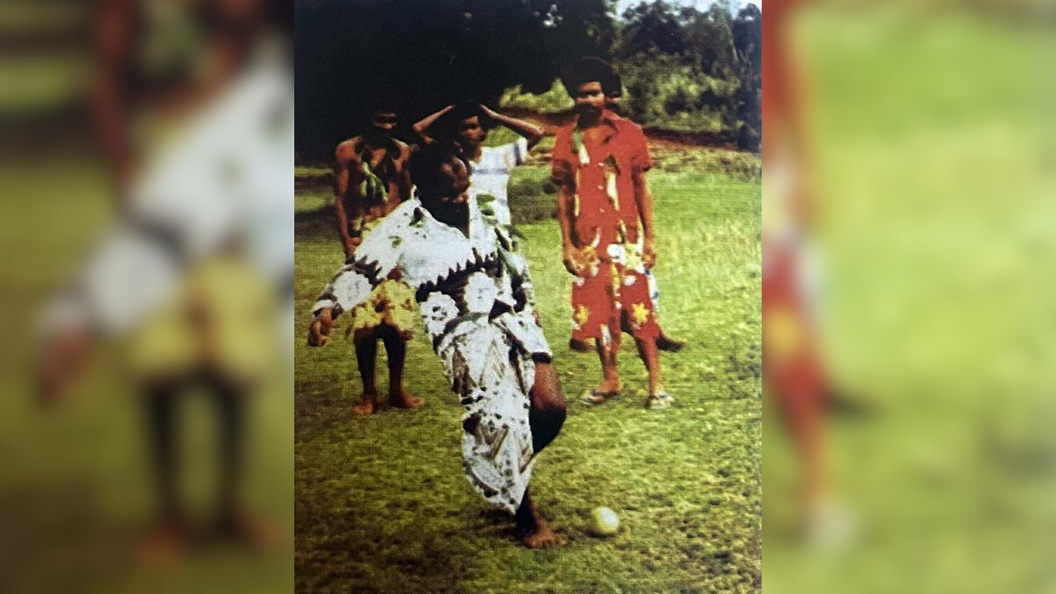

Towards the end of December, Fr Hoare watched traditional Fijian games with fascination. Men played veitiga, throwing long reed-spears across the ground, while women played caqe moli, kicking large oranges.

“The competition was fierce, but there was joy in every throw.

“Winners teased the losers with chants, then presented them with bundles of clothes as gifts.”

An Indo-Fijian youth watched quietly and remarked, “If we Indians were playing, we would all try to lose.”

Fr Hoare smiled, noticing how the games reflected generosity and community rather than the acquisitiveness of his visitor’s culture.

“There were no losers here.

“Just celebration and laughter.”

New Year, new vision

Fr Hoare witnessed a remarkable New Year ritual at Vudibasoga.

Indo-Fijian Christians waded into a river at midnight, blindfolded with strips of paper listing cultural prejudices. As the clock struck twelve, they submerged themselves and released the blindfolds downstream. Then they lit candles along the riverbank.

“They had just spent three days living with iTaukei villagers. They ate together, worked in the fields, learned crafts, even hunted wild pigs. They saw generosity, unity, and joy in everyday life.”

Tears flowed freely during farewells.

“Many of them told me that their fears and prejudices were gone.

“They were ready to step into the New Year with a new vision, healed of old biases and open to the human family.”

Ending another year

It’s clear that connection, empathy, and shared experiences can bridge even deep divides. In today’s Fiji, where ethnic and social tensions still emerge in politics and our communities, this story reminds us that understanding doesn’t come from distance, it comes from engagement.

When people live alongside one another, share meals, work together, and celebrate each other’s traditions, prejudices dissolve. Sadly, you don’t see that as often today. The challenge now is to carry that spirit beyond small villages and church halls into schools, public institutions, and our wider society.

- Next week in The Fiji Times, we’ll continue this journey together into the following year.