Nowadays, we often speak of the Catholic mass as though it is something distant. I’ve heard people say it no longer speaks to them, that the readings feel heavy and the rhythm too slow for the pulse of modern life.

But beneath these complaints lies something deeper: a yearning for meaning.

Columban priest Fr Frank Hoare who spent decades among the people of Fiji, understood this tension well.

For those of you who just joined, Fr Hoare wrote about this time serving as a missionary here in Fiji and if you were following, you know that for him, worship was never a museum piece.

It was alive, rooted in the struggles and joys of ordinary people.

And nowhere was this clearer than in the story of Fr Kusitino Cobona.

Fr Kusitino

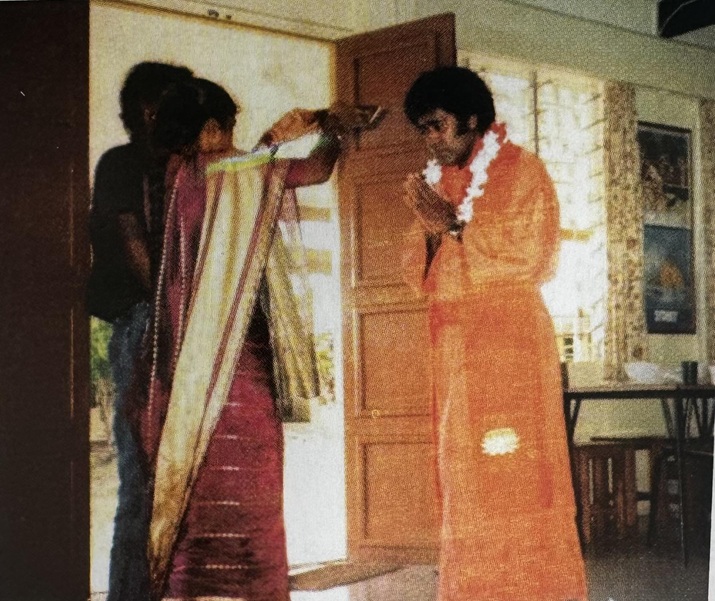

Fr Kusitino, an indigenous Fijian priest, began his ministry by stepping into another world.

As a seminarian, he lived with an Indo-Fijian family, learning Hindi and absorbing not just a language but a way of life.

He shared their meals, their fears, their hopes.

Through them, he discovered that understanding another culture isn’t a matter of study, it’s a matter of the heart.

“So when he celebrated mass in Hindi, he didn’t simply translate the prayers,” Fr Hoare said.

“He wove Indian gestures into the Eucharist, the deep bows, the placing of flowers around the gifts, the glow of camphor rising from a brass tray.”

According to Fr Hoare these were more than symbols, they were bridges.

Fijians who attended his Hindi mass were moved by its solemn grace, reminded of their own traditions of respect. Indo-Fijians were touched even more deeply.

“It felt like the priest was speaking to us from inside our own home,” one elderly woman told Fr Frank as she embraced Fr Kusitino after Mass.

During a time that was scarred by coups and separation, this simple act of cultural empathy became a quiet force of reconciliation.

He compared such situations to what St Paul wrote, “By his death on the cross, Christ destroyed their enmity.”

The gift of a name

Years later, in November 2000, as Fr Frank prepared to leave Fiji for six years of service abroad, he sought a way to remain connected to a family who had become dear to him. In his hands he held a tabua, a whale’s tooth, the most treasured symbol in Fijian custom.

A tabua is never given lightly; it carries weight, honour, and request.

He offered it to the family, asking that their unborn child be named after him.

The father, holding the tabua with the respect it demanded, announced that such a request meant the child must be a boy.

Fr Frank laughed gently.

“If it’s a boy, call him Francis,” he said. “But if it’s a girl, please name her Frances.”

Weeks later, a baby girl entered the world and she was given the name he had hoped for.

A small gesture, perhaps.

But for Fr Frank, it was a reminder of how relationships, like rituals, bind us together long after we part.

The chief and the mango tree

Fiji’s political landscape, however, was not always so gentle.

Fr Frank remembered the sting felt by many indigenous Fijians when a 1984 Australian television introduction claimed that a former Prime Minister’s ancestors “clubbed and ate their way to power.”

The insult cut deep, and copies of the program circulated, fuelling outrage.

By 2006, after yet another coup, tensions rose again. The Great Council of Chiefs, once a symbol of indigenous authority, was disbanded.

In a moment that shocked many, the coup leader suggested that the chiefs “sit under a mango tree and drink home brew.”

A provincial chief pleaded with soldiers from his province to return home, but his words fell on unmoved ears. Something had shifted.

Seeking clarity, Fr Frank visited Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi, a chief known for his wisdom and balance. When asked whether the status of chiefs was fading, Ratu Joni’s response was calm, unshaken.

“The loss of chiefly status does not concern me,” he said.

“What troubles me instead was the erosion of the values that had long held Fijian communities together such as the solesolevaki (working together), veirokovi (respect), and veirogorogoci (listening to one another).

“These were the pillars of a nation.”

What it all means for us today

We circle back to the same theme that unity is never automatic.

It grows in small, human moments where understanding replaces suspicion and empathy replaces distance.

These stories teach us that reconciliation is not achieved through grand gestures, but through the quiet, everyday courage of people willing to step into each other’s world.

As Fiji moves through its Truth and Reconciliation process, listening to painful memories of the coups and the communities they fractured, these lessons feel even more vital.

The testimonies we hear remind us that healing requires humility, patience, and above all, a willingness to truly listen.

If we are to build a more cohesive and compassionate Fiji, we must return to these values, choosing respect, choosing understanding, and choosing to walk forward together, one story at a time.