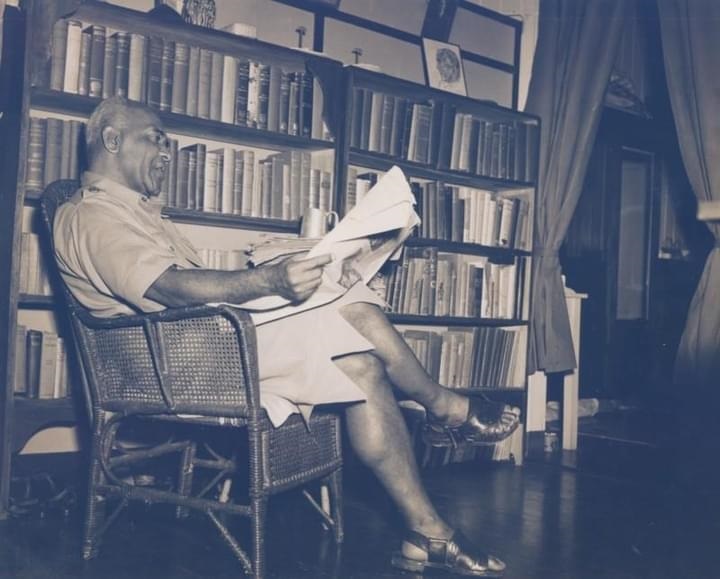

Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna was one of the most influential sculptors of I Taukei power and politics in the colonial era. Sukuna was the grandson of Adi Asenaca, the second daughter of Ratu Seru Cakobau’s first wife. Since chiefly status was traced through male descent, Sukuna was a low ranked chief. He was educated in New Zealand and then at Wadham College in Oxford. He graduated after serving with the Foreign Legion during World War I in France (where he won the Medaille Militaire) and in 1921, he was called to the Bar at the Middle Temple. Despite being a low ranked chief, as the first overseas-educated chief, Sukuna would play a prominent role in defining I Taukei power.

Two significant changes occurred in Fiji while Sukuna studied overseas. First, the colonial government reduced the power and influence of chiefs in the Native Administration by reverting to direct rule policy. The colonial government argued that the chiefs had failed to develop the I Taukei community and moreover were an obstacle to I Taukei development because of the excessive traditional customs they laid on people. Thus, in the early twentieth century, the colonial government made several changes to the Native Administration. It returned power and leadership in the district and provincial levels to European officials and confined chiefs to rural assignments. The colonial government also introduced the individual farmer concept for I Taukei economic development. Finally, in 1916, the colonial government abolished the Native Administration altogether. I Taukei chiefs and officials however, continued to administer I Taukei affairs at the local level.

Second, the government abolished the indenture labor system in 1920. Approximately 60% of the 62,837 Indians that came through the indenture labor system chose to permanently reside in Fiji. By 1936, most of the Indians were cane growers, either as independent farmers or as tenants of the Colonial Sugar Refining Company(CSR), while others cultivated rice, cotton, and bananas. The Indians soon became the main producers in the sugar industry, the backbone of Fiji’s economy. Furthermore, the arrival of Indian business and professional immigrants from Gujerat and Punjab Indian boosted the economic status and power. At the beginning of 1920, the Indian’s (especially those born in Fiji) identity and social consciousness underwent a significant change.

Their social outlook was quite different from those of their parents. They had no memories of India. Fiji was their homeland and as a result they wanted to defend their rights and pursue opportunities in the land of their birth. Thus, a new social identity emerged, that of the Indo-Fijian. By the early 1940s, Indo-Fijians had established themselves as an integral sector of Fijian society. In 1956, Indo-Fijians outnumbered the I Taukei population and this trend continued until 1987. With their new social and economic status, Indo-Fijians called for political equality, fair political representation, and secure land tenure. The European community on the other hand, interpreted Indo-Fijian’s economic and political progress as a threat to I Taukei interests. The Europeans considered it their duty to protect I Taukei interests as stipulated in the Deed of Cession. Meanwhile, the I Taukei continued to lag behind in modern economic developments. This was the Fijian context that Ratu Sukuna confronted when he returned from his studies.

Ratu Sukuna adamantly believed that the Native Administration and the Bose Vakaturaga were foundational institutions for I Taukei development. He firmly supported Mitchell on the re-establishment of the former indirect rule and the Native Administration. However, he insisted that the Native Administration not merely step back into Gordon’s colonial strategy; rather it should advance the social, economic, and political development of the I Taukei. He wanted to bring the I Taukei on par with the social, economic, and political level of the other Fijian communities. However, like Gordon, Sukuna viewed the economic and political development of the I Taukei to be a gradual process. Sukuna’s speech on the Fijian Affairs Bill reflected his conservative vision.

… the Fijian outlook is only now emerging from the feudal age…What constitution and what form of laws then do we consider the best suited for a people in this transitional stage? The constitution which has shaped you [the Europeans] is not the same as ours; they are not comparable things; they belong to different ages and different hemispheres. If a comparison of achievement has to be made at all it must surely be made with people akin to us in the Solomons and Tahiti, Samoa and the New Hebrides, Tonga and New Caledonia. Make that comparison and you will find that the Fijian system has achieved good results and is capable of development along its own lines. Are we going to do that or are we going to impose modern ideas of government on the Fijian?…Now some of us regard equality as a sacred thing that should be bestowed on all communities – social equality, equality of opportunity and equality before the law. So do I; but all in good time when every community has acquired the necessary elements that go to make equality a good…Sir, the purpose of this Bill is to train Chiefs and people in orderly, sound and progressive local government better to fit them for the eventual give and take of democratic institutions.

At the Administrative Conference in 1944, Sukuna clarified his vision regarding the Native Administration. One, that Fiji being primarily an agricultural country, it was imperative to maintain the closest possible connection between the individual and the land. Two, that it was important to discourage any tendency toward the disintegration of [I Taukei] society. Three, that in order to provide the necessary incentive for the continuation of village life, it was necessary to improve the basic material conditions in the villages by better housing and social services.

Ratu Sukuna believed that the success of the Native Administration depended on five key elements.

- First, the need to form larger political and social organizations, for the kinship group was too small a base in itself to achieve the development he had in mind.

- Second, the need for an external exchange economy to provide outlets for [I Taukei] produce.

- Third, the need for internal and external markets.

- Fourth, the actual increase in the quantity of cash crops grown by the [I Taukei].

- Fifth, education of a type suited to the Fijian environment.

Despite his ambitious vision, Sukuna knew that the success of the Native Administration depended on the leadership of the chiefs. He admitted that the chiefs were not well equipped nor trained to provide the kind of leadership needed for modern economies and political governance. This was his dilemma. Hence, Sukuna proposed that the Native Administration should educate chiefs and potential leaders in modern economics and politics. He sent some chiefs and commoners for education overseas and among these was Ratu Kamisese Mara, who would later become the first prime minister of Fiji.

Ratu Sukuna recommended practical changes within the Native Administration structure. The first had to do with the title; he renamed the Native Administration as the Fijian Administration. He proposed that larger villages should be created because it would mean greater access to resources for development and social services. He posited that the larger villages offered young people, whose energies were needed for economic development, an attractive environment. Sukuna reduced the number of provinces from nineteen to fourteen and likewise the number of districts from 186 to 74. Sukuna employed many I Taukei commoners in various departments of the Fijian Administration. However, despite these changes, little progress was made in the economic and political development of the I Taukei. These changes only concerned the internal affairs of the Fijian Administration. Sukuna resolutely believed that preservation of the I Taukei traditional way of life and the chiefly system were essential components of the economic and political development of the I Taukei. Hence, the Fijian Administration continued to isolate the I Taukei from global economic and political developments. Sukuna headed the Fijian Administration for approximately ten years. He retired in 1954 and was succeeded by G. K. Roth, another advocate of neo-indirect rule.

Ratu Sukuna’s Vision

Ratu Sukuna can be seen as the Dr Martin Luther King or Nelson Mandela of Fiji. He had a dream for the Itaukei. I have a dream. Although Sukuna was educated in the British colonial world he deeply believed in moving beyond the British colonial framework. He envisioned that Fijians are not Europeans and need a unique economic and political framework for development. Sukuna had two clear goals:

- To advance Itaukei political and economic development.

- To educate of chiefs and Itaukei leadership

As Fiji searches for ways to develop the Itaukei people, Ratu Sukuna’s vision will be worth reflecting on. We live between the tensions of neo-colonialism (globalization) and local (itaukei development). Like Ratu Sukuna, we must take on the benefits of globalization while at the same faithful to the unique development of Itaukei. Our Itaukei leaders and chiefs will do well to go on a Ratu Sukuna retreat as a way of making Ratu Sukuna day.