I have lived through two coups, yet I did not understand, back then, that history was happening outside my bedroom window.

In May of 2000, I was in Grade 2. To a seven-year-old in Lautoka, the upheaval was merely a disruption of routine; I stayed home because I was told to. Schools closed, roads emptied, and the country folded into itself like a frightened animal. But inside our home, life pretended to continue. My mother cooked the same way, standing over the kerosene stove. My father read The Fiji Times as though the pages were not carrying the weight of a nation trembling. I remember wondering why everyone kept saying, “Just stay home.” Why home, suddenly, felt both safe and unsafe.

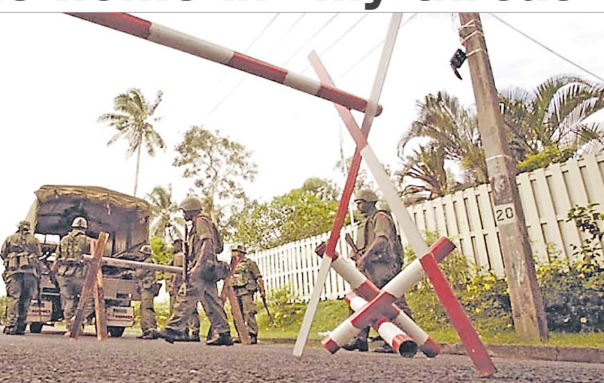

BY December 2006, I had just finished Grade 8. I was on the cusp of high school, old enough to sense the tension, but young enough to lack the vocabulary for it. When the military took over, I did not know that the silence in the streets was not normal, or that soldiers on the 6pm news were not mere characters in a drama. I only understood the tone. I saw the way my parents whispered, the way the whole country’s frequency shifted.

I didn’t realise those days were shaping my psychology—teaching me to lower my voice when speaking about authority, to scan adults’ faces for danger, and to flinch at sudden silence. It taught me to carry a certain humility that does not always belong to me, but sits on my shoulders like an inherited survival tactic. I understood fear before I understood politics.

The gaze that says, “but where are you from?”

That sense of displacement followed me long after the dust of the coups settled, manifesting most acutely in the place I was supposed to call my ancestral home. I have visited India four times in my life. Each time, I went searching for something I could never name, but always felt I lacked: a root, a belonging, a peace. My ancestors left those shores nearly 150 years ago as indentured labourers, yet every time I return, India feels foreign, overwhelming, and impossibly vast, like trying to read a book written in a language I should understand, but don’t.

And each time, when I introduce myself, the script begins:

“Where are you from?” “Fiji.” A pause. “No, but where is your home?” “Fiji.” A longer pause, followed by eyes tightening with doubt, suspicion, or mild confusion. “But your real home?”

In that gaze, I realise my body carries a story India has forgotten. Fiji remembers it, but India does not recognise it. I leave India each time feeling heavier, not lighter. I find only reminders that I am neither here nor there; too Fijian to be Indian, too Indian to be seen as fully Fijian by the world outside. And yet, this in-between identity is the only one I know how to inhabit.

The voice that betrays and completes me

People say accents reveal where you come from. Mine reveals where I never left.

My Fiji-Hindi accent slips out even when I try to tuck it away. I have taught in Auckland, UAE, Kuwait, and now Tokyo, standing in classrooms where my students’ English is shaped by Korean textbooks, British curricula, and American movies.

And there I am, in the middle, sounding like Lautoka Market meets the Navtarang Breakfast Show.

There is a duality to this sound. Sometimes, I carry it with shame. The world often interprets a Fiji-Hindi accent as “less educated,” “less global,” or “less polished.” I have felt the heat rise in my cheeks when I hear myself speak at staff meetings.

I have seen parents’ eyebrows lift ever so slightly when they hear my voice for the first time. In moments of insecurity, I have softened my vowels to sound more “international,” more “neutral,” more acceptable.

But I always return to my natural voice. I have to. Because that voice belongs to a people who survived indenture. That accent was born out of broken Bhojpuri, Avadhi, and Hindustani colliding on a plantation and becoming something new. It carries the laughter of my grandparents, the scoldings of my teachers, the rhythm of Fiji’s open-air buses, and the prayers at my family’s small mandir.

My accent is not polished. It is a history book. It is a rebellion. It is a home I carry in my throat.

The privilege of leaving, and the privilege of returning

I often wonder: Would I have this life, this freedom to teach internationally, to move across continents, to casually book a ticket to Seoul or Dubai or Osaka, if I held a Fijian passport?

Would I pass through immigration lines as easily? Would embassies stamp my passport without hesitation? The hard truth is: Probably not.

My New Zealand passport is a privilege I did not earn, but inherited by migration. It allows me to become an “international educator” rather than “a brown man from a coup-prone island nation trying his luck abroad.” It smooths borders, softens questions, and grants me possibilities my own family back in Fiji might never have.

I carry that privilege the same way I carry my accent — uneasily. I am aware of its weight, aware of its injustice, and aware that I belong to a generation that survived political instability yet used mobility as its escape hatch.

In airports, I glide through lines my cousins cannot. In visa queues, I skip the rituals of proving my financial worth. In job applications, I am seen as “global,” not “third world.” But privilege does not erase memory, and it certainly does not unlearn fear.

The world that made me

I have lived in so many countries now that my passport is beginning to look like a scrapbook. Yet the more I travel, the more I understand how deeply Fiji lives in me. It is in my instinct to choose humility over confrontation.

It is in my habit of scanning crowds for danger, the leftover ghost of coups past. It is in my need to belong everywhere yet nowhere. I stand in Tokyo today, thousands of miles from Lautoka, but the Grade 2 child who stayed home during the upheaval — the one who didn’t know he was watching history — is still inside me. I stand in India searching for ancestors who will never return my gaze.

I stand in classrooms across continents, teaching children whose lives seem so distant from the one I left. And my voice — my imperfect, ever-shifting Fiji-Hindi voice — reminds me that identity is not a destination. It is a sound.

A feeling. A memory whispering itself into every sentence.

I sometimes wonder if the reason my accent refuses to disappear is that it is the only anchor I have left.

I have left countries, jobs, relationships, and entire chapters of my life behind. But the accent stays. Stubborn. Loyal. Unapologetic. Maybe it knows something I don’t.

Maybe it knows that every time I say, “I’m from Fiji,” I am reclaiming a story that the world often doubts. Maybe it knows that privilege may change my passport, but it cannot change my roots. And so, I write.

I write because privilege makes it possible, but memory makes it necessary.

I write because somewhere in India, or Japan, or New Zealand, a stranger will still ask me, “But where are you from?”

And I will still answer, proudly and softly, “Fiji.”

Because in the end, no matter where I go, Fiji does not leave me. Not in my accent. Not in my story. Not in my heart.

ASHNEEL JAYNESH PRASAD is a Fiji-born educator currently based in Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan. He frequently contributes to this newspaper on themes of identity, cultural heritage, and social reform.