Last week, we brought our discussion to 1874 when the Deed of Cession was signed. We saw how Cakobau was pressured and left with little choice but to ask for help from Britain. This came about because of mounting debts to the US as astronomical interest rates were heaped on until he was overwhelmed. Then there was pressure from his white supporters as well as others who wanted political stability to make progress in an increasingly promising land. Thirdly, he was faced with waning influence as other chieftains, who had once worked closely with him, had begun to exhibit enterprise and independent conduct in their dealings especially with traders and merchants. Cakobau needed to be recognised as a central figure in the power structure in Fiji and cession would ensure this as he would play a pivotal role in the process as the Tui Viti. Here we look at the actual signing of the Deed of Cession.

The signing

Researching through a number of records, the following can be gleaned about how the actual signing of the Deed of Cession was carried out and how it looked on the day. There was heavy rain in Levuka on the morning of 10th October 1874. This forced the shifting of the ceremony to 2pm that afternoon. The warships berthed at the harbour were the Pearl and Dido and by 2pm some 200 sailors and marines had disembarked to await commencement of the ceremony. The Fijian side had the Fijian Armed Constabulary.

This is how it was arranged according to research carried out by The Fiji Times (10/10/2015), “the Fijian armed constabulary were drawn up on the town side of Flagstaff near the landing-stage and Nasova, the mariners and sailors formed up on the landward side, leading citizens of Levuka who were grouped on the third side, therefore forming three sides of a hollow square open towards the sea”.

At 2.15pm, as His Excellency Sir Hercules Robinson and Commodore Goodenough left the Pearl, and walked through the “hollow square”, a 17-gun salute was fired from the ship. Waiting at the landing stage to accept the two Royal representatives were Captain Chapman (of the Pearl) and Mr Edgar Layard, HBM Consul for Fiji and Tonga. The Fijian Armed Constabulary saluted as they crossed the lawn to where Cakobau waited in the King’s Room. Anyone entering that room had to stoop and bow to avoid the beam of native Fijian wood.

This was the room in which Cakobau had conducted his business of government during his ill-fated attempts to form government from 1865 when he formed the Confederacy of Fijian Chiefs, to 1871 when a constitutional monarchy was established with the help of Australian colonists who were now obviously looking at securing longer term interests in Fiji. It was soon obvious that even though Cakobau was installed as King the real power lay with his fragmented and bickering white backers. That aside, Cakobau sat on the pinnacle of power with all its accoutrements in 1874 when the Royal Envoys stooped to enter his sanctum.

It was this seat of power that His Excellency Sir Hercules Robinson and Commodore Goodenough envisaged when they entered the room in Levuka. Both the representatives of the Crown were duly conducted to seats at the table, taking their places on the King’s right. Records noted that the rest of the company, both British and Fijian remained standing throughout the proceedings. Why these optics are being emphasised here is because it would have clearly impressed on witnesses present who was really in charge in Fiji. Cakobau was seated ostensibly comfortably in his domain as the proceedings unfolded.

The Deed of Cession was then read, in Fijian, for the benefit of those chiefs who had not heard it previously. Before the signing, Cakobau asked the chief secretary Mr Thurston if he might read a paper which Ratu Cakobau had given him that morning. Mr Thurston then read (FT 29/02/2017):

“Your Excellency, before finally ceding his country to her Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, the King desires, through your Excellency, to give Her Majesty the only thing he possesses that may interest her. The King gives Her Majesty his old and favourite war club, the former, and until lately, the only known law of Fiji. In abandoning club law, and adopting the forms and principles of civilised societies, he laid by his old weapon, and now as your excellency sees, it bears upon it the emblems of peace and friendship. The king says that under the old law many of his people — whole tribes passed away and, disappeared but hundreds of thousands still remain to learn and enjoy the newer and better order of things. With this war club, the king also sends his love and respects to the Queen of England and says that he fully depends upon Her Majesty and her children who succeeding her shall become kings of Fiji to exercise a watchful control over the welfare of his children and people, who, having survived the era of barbaric law, are now submitting themselves, under Her Majesty’s rule to civilisation.”

This is how Cakobau laid aside and put behind the barbarism of club law and embraced the principles of civilised societies. The surrender and offering of his war club – Nai Tutuvi Kuta ni Radini Bau – as a present embodied a commitment that was fulfilled with pride especially after 1970 when we gained independence. Cakobau’s war club was the legendary Mace of the Parliament of Fiji. It served as a silent, yet powerful reminder of that collective commitment made by the signatories of the Deed of Cession until attempts were made to trash it during the Speight Coup of 2000. It returned to parliament in 2015. But that is another story.

The signatories

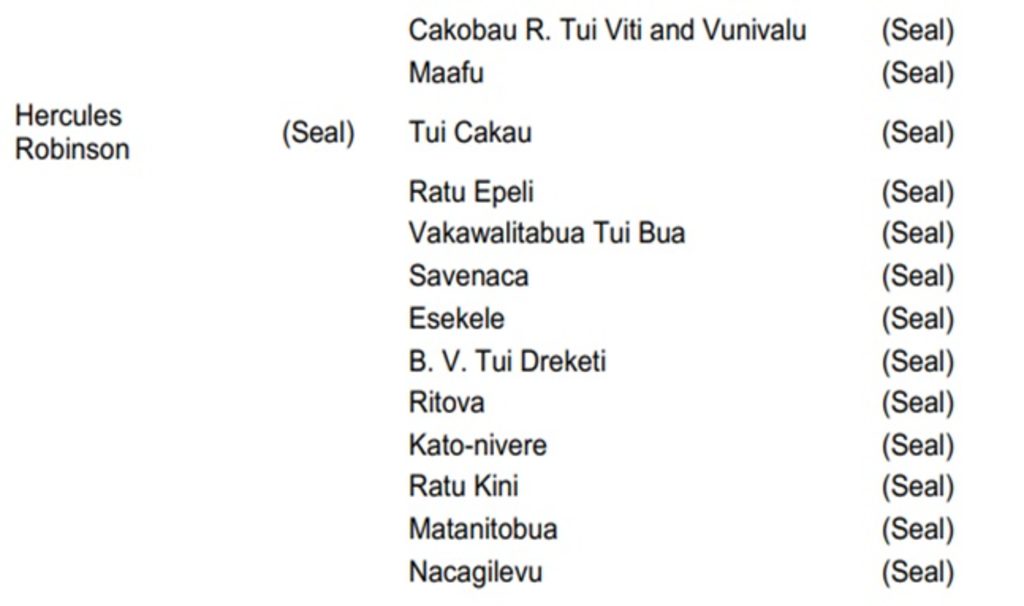

The 13 signatories to the Deed of Cession that gave away sovereignty over Fiji to Queen Victoria were all considered at the time, in their own right, as dominant chiefs who exercised sovereignty over their domains that made up different parts of Fiji. The names and affiliations/positions were as follows:

It needs to be noted that, of the 13 signatories, three were from Bau: Cakobau and two of his sons – Ratu Epeli Nailatikau and Savenaca Naulivou. A further two, Tui Tavuki (Kadavu) and Roko Tui Viwa (Viwa) were long term unwavering allies of Cakobau. The Tui Cakau (Cakaudrove iSokula) and Roko Tui Dreketi (Rewa) had kinship relationships through marriages. Namosi, Nadroga, Macuata and Lau also had kinship relationships with Bau. Lau, a long-time ally was now in the firm hands of Ma’afu who was the only veritable rival of Cakobau in Fiji after 1858 – he also had the support of Bua and Cakaudrove. These were the 13 signatories to the Deed of Cession.

It is interesting that all of the leaders cited here were maritime chiefs (bar Nadroga and Namosi). This is because Fiji was and still is an island country. The transportation systems at the time were primarily water-based. That is how settlements sprouted close to water routes and preferably where there was natural protection in case of attacks. Some might argue that Nadroga does qualify to be called a coastal kingdom. However, the bulk of maritime traffic at the time did not go past Nadroga; it moved on the other side of Viti Levu. Coming back to the list of signatories, it needs to be noted that Macuata had two contenders for paramountcy of their domain; both signed the Deed of Cession in a clear attempt to legitimise their claims and avoid being left out when the new colonial regime took over.

There were, however, parts of Fiji that refused to submit to cession. We will pursue that next week.

The Sacred Heart Parish Catholic Church in Levuka. Picture: SUPPLIED

Signatures on the Deed of Cession. Picture: SUPPLIED