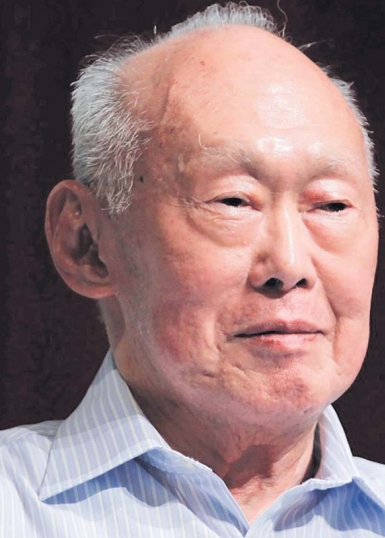

When Singapore separated from Malaysia in 1965, it was a fragile, poor, and deeply divided society. Poverty, unemployment, opium addiction, prostitution, and slums were everywhere. Racial riots between Chinese and Malays had shaken the island. The country had no natural resources, no army, and no guarantee of survival. Its Chinese community made up nearly three-quarters of the population, and its new Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, himself was ethnically Chinese. The easy path, and the politically expedient one, would have been to construct a state built on Chinese dominance. But Lee was not a parochial politician. He was a Cambridge-trained lawyer, among the most educated leaders of his time, and a man who combined intellect with pragmatism. He recognised a brutal truth: if Singapore became a “Chinese state,” it would remain forever divided, unstable, and poor. Only by building a multiracial nation, one in which Malays, Indians, Eurasians and Chinese were truly equal (before the law and in practice), could Singapore prosper. That conviction became the foundation of what the world now calls the “Singapore miracle”.

Building equality in daily life

LEE Kuan Yew understood that it is not enough to add the word ‘secular’ to the Constitution. This does not ensure equality in the country as people are skeptical. When people from different religions and ethnicity live in a country, with high communal tensions, people doubt each other. They do not want to socialise with others. To solve this problem, Lee Kuan Yew took a proactive approach to integration.

Lee Kuan Yew understood that harmony could not be left to chance. Societies divided by race tend naturally to segregate. Ghettos form, suspicion grows, and tensions ignite. To achieve a truly multiracial society, Lee introduced innovative and, at times, tough measures:

Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP): In the late 1960s, Lee’s government created vast public housing projects to replace Singapore’s sprawling slums. But unlike in many countries, allocation was not left to market forces or individual choice. Instead, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) imposed ethnic quotas on every block. If Singapore’s population was 74 per cent Chinese, 13 per cent Malay, and 9 per cent Indian, then roughly that ratio would be enforced in every housing estate. A Chinese family would likely have a Malay or Indian neighbour. Children of all races would play together in the same courtyards. This broke down barriers and prevented the creation of racially homogenous enclaves. Even today, over 80 per cent of Singaporeans live in HDB flats, meaning the EIP continues to shape everyday social contact.

Religious Harmony Act (1990): Lee recognised religion as another potential fault line. He set up the Presidential Council for Religious Harmony, with representatives from all major religions, to monitor and defuse tensions. This was backed by law: any religious leader inciting hostility could be restrained. By making secularism the default principle, Lee ensured that Singapore would never be dominated by one religion at the expense of another.

Racial Harmony Day: Introduced in schools in the 1990s, this annual event requires children to dress in the traditional clothing of another culture, read aloud a “Declaration of Religious Harmony,” and learn about the traditions of their peers. From a young age, children internalise the idea that diversity is to be celebrated, not feared.

These policies were not cosmetic gestures. They changed daily life. They forced people to interact, to respect one another, and to build trust. Through eliminating segregation and institutionalised privilege, Singapore created social cohesion, stability, and a sense of shared destiny.

A secular civic identity

Lee Kuan Yew insisted that Singapore would not be built on race, religion, or language. “We are not a Malay State, we are not a Chinese State, we are not an Indian State,” he declared. Citizenship, not ethnicity, defined belonging. This was revolutionary in Southeast Asia, where most countries built identity around the dominant race or religion. This civic nationalism gave minorities real confidence. Malays and Indians, though numerically small, could feel ownership of the state.

Institutionalising meritocracy

For Lee Kuan Yew, equality was not just about slogans but rather about building institutions that rewarded ability:

Education – Primary education was made compulsory, of high quality, and nearly free. Schools did not segregate by ethnicity. Vocational training was emphasised so that young people of all backgrounds could acquire practical skills.

Public Service – Recruitment and promotion in the civil service were strictly merit-based. The Public Service Commission was empowered to select the best candidates regardless of race.

Military — With compulsory National Service, every young man, whether Malay, Indian, or Chinese, wore the same uniform and served the same flag. This built shared loyalty and diluted ethnic divides.

In creating real opportunities for advancement, Lee prevented resentment from festering among minority groups.

Zero tolerance for supremacy

Lee’s stance was uncompromising. He rejected calls from Chinese chauvinists who wanted the majority to dictate the state’s character. He also resisted pressures from Malay leaders who wanted special privileges. Instead, he stood firm on the principle of equal treatment for all citizens.

He knew this was politically risky, yet he persisted because he saw that favouring one race would condemn Singapore to endless conflict. Prosperity, he knew, was impossible without fairness.

Why it worked

The results speak for themselves. Within one generation, Singapore moved from being a riot-prone slum colony to a global financial hub. This was not due only to ports, airports, or foreign investment. Those mattered, but they would never have come without stability. Stability, in turn, was built on multiracial trust and equality.

Today, Singapore is among the richest and cleanest nations in the world, with negligible corruption and one of the highest standards of living. It is a society where different ethnicities live side by side not by accident, but by design.

Singapore’s enduring commitment to multiracial politics

Nearly six decades after independence, Singapore remains steadfast in its commitment to multiracialism and secular politics. The spirit of Lee Kuan Yew’s founding philosophy continues to guide its leaders even today. During the 2025 general election, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong reaffirmed that “identity politics has no place in Singapore” and that “we should never mix religion and politics.” Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong similarly cautioned that any attempt to mobilise support along racial or religious lines “is not how politics is conducted in Singapore.” These statements reflect a bipartisan consensus that transcends ethnicity and party lines. Opposition leader Pritam Singh also reiterated that the Workers’ Party “cannot be a successful political party if we play the race and religion card,” pledging to uphold the country’s secular and multiracial ethos.

This persistent rejection of identity-based politics underscores Singapore’s understanding that its peace and prosperity rest on shared civic values rather than communal loyalties. Leaders from both sides of the aisle continue to defend this principle, recognising that the moment politics becomes tribal, harmony and progress are at risk. Singapore’s model of multiracial democracy thus remains not only a legacy of Lee Kuan Yew’s era but also a living national discipline; one that Fiji and other diverse societies would do well to emulate.

Fiji: The price of ethnic politics

Fiji offers a stark contrast. Instead of building a shared national identity, political leaders repeatedly fell back on highlighting ethnic differences. Successive coups and constitutional changes were justified in terms of protecting one race against another. Instead of investing in integration, leaders entrenched segregation — separate schools, separate political parties, and parallel social structures that reinforced division rather than unity.

The results have been devastating:

Political instability: Coups in 1987, 2000, and 2006 eroded democratic institutions.

Brain drain: Tens of thousands of educated Indo-Fijians emigrated, taking skills and capital with them.

Economic stagnation: Investors grew wary of a society prone to ethnic conflict.

Fractured communities: Suspicion and mistrust became entrenched, undermining social cohesion.

Instead of building cohesion, Fiji’s political leaders allowed or even encouraged division, squandering opportunities and eroding prosperity. Unlike Singapore, Fiji has natural resources, fertile land, and a small population. Yet it lags far behind in prosperity because ethnic politics has poisoned its foundations.

The lesson Fiji cannot ignore

Lee Kuan Yew’s intelligence and education allowed him to rise above the temptation of majority rule. He could have built a Chinese-dominated state, but instead he built a nation grounded in equality and merit. He institutionalised fairness, compelled integration, and fostered harmony- not because it was easy, but because it was right. That is the essence of statesmanship.

Fiji’s history shows what happens when the opposite path is taken. Ethnic conflict drains energy, talent, and trust. It undermines democracy and weakens the economy.

The miracle of Singapore is not just about skyscrapers and ports. It is about a man with a vision who insisted that no race or religion would stand above another. Lee Kuan Yew was right, and his legacy proves it. For Fiji, the lesson could not be clearer: until we build genuine social cohesion, we will never unlock our true national potential. And until we do, every Fijian is worse off. As we marked Fiji’s Independence Day and reflected on our post-independence journey, we are left to ponder — what might Fiji have become if it had chosen the path of integration and equality, instead of surrendering to the politics of ethnicity?