I REMEMBER the heat of the afternoon sun in Lautoka, the Sugar City, filtering through the louvers of a classroom that felt more like a courtroom than a place of wonder. My earliest memories of the Fiji education system are stained with the bitter taste of comparison. We weren’t children exploring a world; we were data points in a rigid, cold hierarchy. The school year wasn’t a journey of growth or a blossoming of talent; it was a grueling, high-stakes countdown to the midterms, the term-ends, and the annual exams.

I can still feel the heavy silence that would blanket the room when the results were finally released. I remember the gleaming prizes for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd place “winners” – the chosen few who were told they were the future – while the rest of us were left to feel like sour grapes, discarded, overlooked, and deemed “less than”.

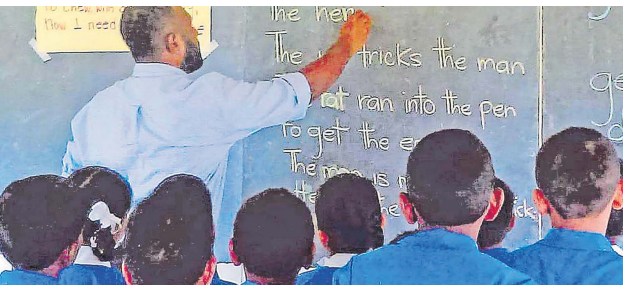

But the deepest scar, the one that still throbbed years later, came from a teacher who believed that public shame was a legitimate pedagogical tool. He would stand at the front of the classroom, clutching the mark sheets like a weapon, and yelled out student after student, reading every name and every mark from highest to lowest.

With every name called, with every descending digit, I felt my heart, my grit, and my dignity erode. It wasn’t just a grade; it was a public evisceration of a child’s self-worth. It was a message that if you didn’t fit the narrow mold of academic excellence defined by a colonial relic, you didn’t matter.

This isn’t just a personal memory; it is the lived, painful reality for generations of Fijians. The Fiji education system, as it stands today, is neither empowering nor uplifting. It is a system that lacks a “Fijian soul,” a hollowed-out structure that prioritises rote memorisation over the actual human beings sitting at those wooden desks. We have to speak the bitter truth: the British officially left Fiji in 1970, but 56 years after the Union Jack was lowered, their rigid, Victorian expectations of education still rule the common people.

Why are we still bowing to a curriculum that doesn’t see us? Why is the ghost of a dead empire still dictating the rhythm of our children’s lives? We live in the heart of the Pacific, a maritime nation, a volcanic archipelago, and a hub of rich indigenous and indentured history, yet our curriculum treats our own culture, our taonga, and our agricultural genius as mere footnotes.

We spend more time memorising the nuances of the Industrial Revolution or the geography of the Thames than we do engaging in a local inquiry into the land that actually feeds us. Even our language is sanitised and stripped of its heart. We have “vernacular” classes, but they often teach Shuddha formal) Hindi – a beautiful language, yes, but not the Fiji Hindi that was birthed in the blood and sweat of the cane fields by our ancestors. By ignoring the local dialect, we tell our children that their “home voice” is wrong, that their unique identity has no place in a “serious” classroom, and that their culture is something to be left at the gate.

Our identity is being drowned by the very oceans we live on and by the relentless tide of migration, yet we continue to teach as if we are a suburb of London in the 1950s. If we do not unpack and value what exists here and now, we will wake up in 100 years with nothing, but a hollowed-out nation and the silent “regret of what if.”

But how can we blame the system entirely when we have fundamentally failed to respect the architects of that system? We claim to value our children’s futures, yet we treat our teachers like disposable labour. In Fiji, a teacher earns “peanuts” – a starting salary that often hovers between $20,000 to $25,000. When you weigh that against the skyrocketing cost of living and the salaries offered in New Zealand or Australia, it is no mystery why our best minds are fleeing.

We are witnessing a massive “brain drain” that is bleeding the country of its wisdom. Why should a brilliant, dedicated educator struggle to put food on their own table in Suva or Lautoka when they could be earning triple that across the Tasman?

Furthermore, we treat experience like an expiration date. We have seasoned, veteran teachers who have lived through every reform and every crisis, yet they are left to retire in silence, their decades of skills discarded. Why aren’t they leading the charge in curriculum reform? Why aren’t they the primary lecturers in our universities, teaching the next generation how to actually survive a classroom?

We have been tricked into thinking that a Master’s degree or a PhD from an overseas university equates to the right to dictate a curriculum, but academic titles cannot replace the wisdom of someone who has lived through the system and seen the look in a child’s eyes when a lesson finally clicks.

The nonsense of nationalisation is another anchor dragging us down. Why is the hiring and placement of teachers treated like a military operation? We must give autonomy back to the schools. Give the school boards the right of governance. The current “posting” system is a relic that is actively driving the younger generation away from the profession.

If a teacher’s life, family, and support system are in Lautoka, why must they be forced to serve four or five years in a remote part of Vanua Levu or a maritime island against their will just to satisfy a bureaucratic checkbox? We have to be realistic – this forced displacement isn’t “service,” it’s a deterrent. It breaks families and it breaks the spirit of the educator.

We need a total rehaul, a revolution of the mind. We need a curriculum where the first years of school are focused on manners, on vakarau, on learning Pasifika history, our songs, and our arts. I want to see a classroom where a student feels represented in the books they open. I am not Shakespeare, and I do not speak in a Shakespearean tongue. Why are we still obsessed with the Capulets and the Montagues when our own stories are more vibrant and more relevant?

Instead of Romeo and Juliet, let us teach Albert Wendt’s Sons for the Return Home. Instead of Hamlet, let us explore the visceral, jagged beauty of John Pule’s The Shark that Ate the Sun. For every Julius Caesar, let us study Vilsoni Hereniko’s The Last Virgin in Paradise or the raw, unapologetic truth of Sia Figiel’s Where We Once Belonged. We need to look at our own shores, find our own voices, and make this education ours.

As for the testing – let us finally speak the truth that the ministry won’t. Whether you score a 100 or a 50, both students have the capacity for immense success. What truly sets people apart in this world is not a mark on a paper; it is intent, it is ambition, and it is hard work. No two brains are wired the same.

You might excel in maths, but struggle with the structure of an essay; you might thrive in the dirt of a farm or the speed of a rugby pitch, but find the periodic table to be a foreign country. The only competition that matters is the one you have with the person you were yesterday. The real question we should be asking is: Have you grown from where you started?

I wish someone had stood at the front of that room in Lautoka and told me this when I was younger. I wish someone had told me that the teacher’s yelling didn’t define my ceiling. Now, it is our responsibility to be that voice. We must break the cycle of this toxic, obsessive focus on marks for the sake of the generations coming after us. You are more than enough. You are enough for yourself, for your parents, and for this world. When you look in the mirror, be fiercely proud of who you are and where you come from.

Don’t let the words of any “ignorant aunties or uncles” at a family function make you question your worth or your talent. They are products of the same broken system that tried to break us, and they don’t know any better, but you do. The world is waiting for you, and your journey is just beginning. Keep striving, keep your head high, and never stop believing in your own brilliance. You are capable, you are resilient, and you are enough.

ASHNEEL JAYNESH PRASAD is a Fiji-born educator currently based in Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan. He frequently contributes to The Fiji Times on themes of identity, cultural heritage, and social reform.