CONSTITUTIONAL reform is not a roadside repair. It is more like working on an aircraft while it is in flight. It can be done, but only with extreme care, broad consensus and meticulous planning. To start pulling at the wiring in the year before a national election is to gamble with the entire system’s credibility — Dr SK Sharma

The country does not need grand promises. Fiji now needs a captain who understands that when the ship is heading toward rocks, the only responsible act is to change course — now, not after the crash — Dr SK Sharma

Fiji enters 2026 not with a single crisis, but with a paralysis of leadership. The past year has revealed a government absorbed in political manoeuvring, constitutional shortcuts, and internal power struggles while ordinary families face rising poverty, failing services and deepening social distress. This paralysis is not accidental. It is the direct result of choices made by the current administration — choices that have prioritised political survival over national progress.

The next twelve months will determine whether Fiji breaks this cycle or sinks further into it. The Prime Minister can steady the nation, restore trust and rebuild institutions. Or he can allow himself to be pulled deeper into the gravitational field of iTaukei nationalism, chiefly lobbying and identity politics that have already cost Fiji fifty years of lost direction. The stakes could not be higher.

Every country has turning points. For Fiji, 2026 is one of them. It is not just another election year. It is a stress test of whether the country still has the capacity, to correct its course peacefully, or whether it will accept a slow, avoidable decline dressed up as politics as usual. Within a single electoral cycle, the country has moved from the promise of “restoration and change” to a mood of fatigue, uncertainty and quiet anger.

The signs are everywhere. Rural families are still waiting for water, electricity and decent roads while national debate is consumed by constitutional wording. Urban households are stretched by the cost of living while ministers argue over who sits where in Cabinet and some still to learn about honesty, transparency, and ethics in politics. Public officers are told to do more with less as portfolios are reshuffled without explanation. The government behaves as if these are normal growing pains. They are not. They point to something more fundamental: a leadership that has lost its grip on priorities.

The danger is not only that 2026 will be mismanaged; it is that the consequences will linger long after the election. A mishandled year will weaken institutions, fracture public trust and push more young people to give up on the promise that hard work and patience will be rewarded in Fiji.

A government stuck in its own machinery

From the outside, the government looks busy. There are announcements, reviews, committees and taskforces. Yet when one looks closely at outcomes, the picture is thin. Policies are floated, then quietly abandoned. Ministers move from one portfolio to another before leaving any real imprint. Agencies are asked to implement “reforms” that arrive without funding, guidelines or timelines. This is not active government; it is motion without direction.

Ordinary people understand this better than the political class. Teachers see new initiatives announced with fanfare and then left to wither. Health workers confront shortages that are explained away as temporary but persist year after year. Farmers receive conflicting messages about subsidies, land use and crop priorities. Businesses are told to invest while watching fiscal statements shift like sand. The sense that the government is “stuck in its own machinery” is widespread and justified.

This paralysis is political, not technical. The coalition has spent too much energy on internal balancing, patronage and appeasing competing interests. Real decisions are postponed, diluted or endlessly revisited. Instead of setting a course and steering, the leadership seems content to drift and react. That is not what Fiji needed after years of centralised control; it needed a government that could combine openness with competence. Instead, it has received neither.

Why the 2013 Constitution is not the problem

One of the most troubling trends of the past year has been the attempt to turn the 2013 Constitution into a scapegoat. Whenever the government is confronted with its own shortcomings, the temptation is to blame “the system” and hint that everything would be easier if only the Constitution were rewritten. This is politically convenient, but intellectually dishonest.

The facts are simple. The 2013 Constitution has functioned for more than a decade. It has delivered four national elections. It has provided a known framework for political competition, rights, and institutional roles. It did not prevent the current coalition from winning office, forming a government and exercising power. It is not a locked cage.

No constitution is perfect. Fiji’s certainly has provisions that deserve review, and any mature democracy should be willing to examine its constitutional arrangements. But timing and motive matter. When a government that has struggled to deliver on basic promises suddenly turns its attention to altering foundational laws close to an election, citizens are right to be suspicious. The Constitution did not cause ministerial instability, policy confusion or economic drift. Those are the products of leadership choices.

Turning the 2013 Constitution into the villain is a way of avoiding responsibility. It diverts attention from the failures of governance by pretending the rules are unworkable. In reality, the rules have been workable enough to run the country; it is the players who have fallen short.

The reckless push for pre–election amendments

If the scapegoating of the Constitution were only rhetorical, it would be worrying but manageable. The real danger lies in the concrete push to change key provisions before the 2026 polls. This is where poor judgment veers into recklessness.

Constitutional reform is not a roadside repair. It is more like working on an aircraft while it is in flight. It can be done, but only with extreme care, broad consensus and meticulous planning. To start pulling at the wiring in the year before a national election is to gamble with the entire system’s credibility.

Fijians have a long memory. They know how often rules around power have been changed by those already in office. When a sitting government moves to lower amendment thresholds, adjust safeguards or alter the balance of institutional authority so close to an election, it creates a simple, corrosive impression: the rules are being tailored to the incumbents. Even if individual changes can be defended on paper, the timing undermines the argument.

The responsible path is clear. Go to the people in 2026 under the existing rules. Seek a mandate for any changes. Commit to a transparent, post–election process that involves broad consultation and independent legal scrutiny. Anything else looks like an attempt to quietly redraw the field lines or the goal post, before the next match.

Electoral engineering and the risk to legitimacy

Beyond the Constitution itself, the talk of revisiting electoral arrangements before 2026 is equally troubling. Elections are moments when the entire nation is asked to trust that its voice will be recorded honestly and counted fairly. That trust is fragile. Once damaged, it is exceedingly hard to repair.

Fiji has endured its share of contested outcomes, logistical failures and disputes over rules. The 2013 framework, for all its critics, has provided a reasonably predictable platform for four successive polls. Voters may not love every detail, but they know roughly what to expect. That predictability is an asset, not a weakness, especially in a political culture still healing from coups and disruptions.

To begin altering registration requirements, oversight mechanisms or counting rules on the eve of an election is to invite doubt. Even the perception that the field is being tilted is enough to weaken confidence. When citizens suspect that electoral engineering is underway, some disengage in disgust, others grow angrier, and almost everyone becomes less trusting of the result, whoever wins.

If the government truly believes electoral reform is needed, the honest approach is straightforward: contest the 2026 election under the current rules, and if returned to power, take reforms through a transparent, consultative process, with full public explanation and independent input. Anything less looks like gaming the system. For a country still consolidating its democracy, that is not a risk Fiji can afford.

The COI saga: transparency replaced by theatre

Commissions of Inquiry are meant to clarify, not cloud; to heal, not reopen wounds. When handled properly, they demonstrate that no one is above scrutiny and that public concerns are taken seriously. When handled poorly, they become tools of political theatre and sources of deeper mistrust. The recent COI sits dangerously close to the latter category.

From the outset, expectations were high. People hoped for a process that would set facts out plainly, allocate responsibility and allow the country to move forward. Instead, they have watched a slow–moving drama of delays, partial disclosures, legal jousting and political point–scoring. Rather than drawing a line under past controversies, the handling of the COI has blurred it, even created more doubts.

The cost is not just reputational. Every dollar spent on prolonged legal wrangling is a dollar not spent on clinics, school repairs or rural infrastructure. Every hour of Cabinet time consumed by managing the fallout is an hour not spent grappling with crime, unemployment or health crises. To many Fijians, the message is clear: when power is at stake, transparency becomes negotiable.

Restoring trust requires a simple discipline: publish the report lawfully, not selectively; explain any necessary redactions in plain language; and allow the courts to do their work where appropriate. Anything short of that suggests a government more interested in managing perception than confronting reality.

The sugar ministry abolition and rural fallout

If constitutional debates feel distant to some, the fate of the sugar sector does not. For many cane communities, the government’s decision to fold the Sugar Ministry into a broader agriculture portfolio felt like a blunt signal: your struggles are no longer a priority. The move may have been justified in bureaucratic language, but its impact on the ground has been profound.

Sugar is more than a line item in an economic report. It is the backbone of many rural economies, a source of identity and a stabiliser for entire districts. When leadership structures dedicated to the sector are dismantled or diluted, farmers are left to navigate uncertainty alone. Who is responsible when mill breakdowns occur? Where do they turn for clear pricing signals or technical advice? How do they plan for planting and harvesting if the policy environment shifts under their feet?

The abolition of a dedicated ministry did not solve any of the sector’s longstanding problems: ageing mills, labour shortages, declining yields, or competition from other crops and industries. Instead, it removed a focal point for accountability and coordination. The impression in rural Fiji is of a government that treats their livelihoods as a secondary concern, to be handled through a generic agricultural lens.

Reversing this perception will require more than words. It will require visible, sustained engagement with cane communities, targeted investment in extension services and infrastructure, and the re–establishment of clear lines of responsibility. Without that, the slow erosion of the sector will continue, and with it the further impoverishment of communities that have already carried more than their share of national sacrifice.

Economic drift: when fiscal policy loses credibility

Economic management is not an abstract exercise for technocrats; it is the foundation of whether families can afford food, medicines, school fees and transport. Yet in recent times, fiscal policy has appeared unstable and unconvincing. Statements change, projections shift, and key actors in the finance space come and go under clouds of controversy.

Investors, both domestic and foreign, are not blind to these signals. They look for consistency, predictability and a sense that difficult choices are being made on the basis of a coherent plan, not short–term political calculus. When they see instability, they hesitate. Projects are delayed, hiring is slowed, and the economy loses momentum.

For low–income households, the consequences are immediate. Any hint of reduced social spending translates into anxieties about welfare assistance, health subsidies and education support. Inflation compounds these worries, eating into incomes that were already stretched. When government appears distracted and divided on fiscal direction, people lose confidence that their basic needs will be protected.

What Fiji needs is not complicated: a credible medium–term economic framework, clear explanations of debt and spending choices, and visible protection of essential services. These are not luxuries; they are minimum requirements for preserving social cohesion in a period of global and domestic uncertainty. The longer the government appears to improvise rather than plan, the more that cohesion will fray.

Communities under strain: crime, drugs and HIV

While the political class argues over constitutional clauses, a different kind of crisis has been advancing in the shadows. Drug trafficking and consumption have penetrated communities that once saw such issues as distant. Violent crime in some areas has risen. HIV, long considered manageable, shows trends that alarm front–line health workers.

These are not isolated phenomena. They are signals that social bonds and safety nets are weakening. When young people see no viable path to employment or dignified livelihoods, the appeal of illicit economies grows. When health systems are under–resourced and stigma persists, people avoid testing and treatment. When communities feel the state is absent except in moments of punishment, cooperation with law enforcement collapses.

A government that is serious about the future treats these trends as urgent national priorities. That means moving beyond sporadic crackdowns and press conferences. It requires investing in prevention, treatment and rehabilitation; strengthening community–based policing; supporting families and schools in dealing with addiction and violence; and confronting HIV with candour and sustained funding. These are politically harder tasks than drafting constitutional talking points, but they are far more important for the survival of the nation.

The return of nationalist politics and chiefly pressure

Layered on top of these structural problems is a familiar and dangerous pressure: the pull of iTaukei nationalism and chiefly politics under the Rabuka government. History has shown what happens when national direction is outsourced to narrow identity agendas and elite traditional interests. Promises are made in the language of protection and pride, but the outcomes are stagnation, division and missed opportunities.

For half a century, powerbrokers have assured iTaukei communities that their interests were being defended. Yet many villages still lack basic services. Children still attend classes in temporary structures. Young people leave for urban centres or overseas because they see no future at home. This has occurred despite the fact that iTaukei own the overwhelming majority of land and receive lease income. The issue is not ownership; it is what national leadership has done — and failed to do — with that reality.

If Rabuka chooses to lean further into nationalist rhetoric or allows chiefly lobbying to dictate the pace and direction of reform, he will not be breaking new ground. He will be returning Fiji to the very patterns that derailed its development and invited repeated interventions in the past. The cost will not be borne by elites in Suva, but by villagers who continue to live with no water, no reliable electricity and little prospect of meaningful economic participation.

A Prime Minister worthy of the moment will refuse to be captured by these forces. He will govern for the whole nation, not for the loudest lobby.

The people’s priorities the government has ignored

When Fijians talk about what matters in their daily lives, they do not begin with constitutional clauses or committee structures. They talk about the basics: the cost of food, the reliability of water and electricity, the safety of their streets, the quality of their children’s education, the availability of jobs, the fairness of public services.

There is a growing gap between these priorities and the agenda that dominates government action. While households juggle bills, leaders joust over legal texts. While communities struggle with crime and health crises, Cabinet devotes time and energy to political theatre. It is as if two different countries are being lived simultaneously: one on the ground, one in the corridors of power.

Bridging this gap requires more than better communication. It demands a reprioritisation of effort and resources. Budgets must reflect the realities of ordinary lives. Policy attention must follow the weight of people’s problems, not the noise of political insiders. When the state feels distant and self–absorbed, citizens lose faith that participation matters. That is a dangerous path for any democracy.

Rabuka’s choice: Steer the ship or wreck it

Fiji has been here before: at a point where leadership decisions either avert crisis or cement it. The present Fijian Prime Minister, himself started this cycle with the first coup of 1987. In 2006, the language of “clean–up” was used to justify drastic interventions because a government was seen as captured, complacent and unable to correct its own course. The context is different today, but the sense of a state drifting while leaders act as if all is normal is uncomfortably familiar.

Rabuka does not have the excuse of ignorance. He knows what happens when a government loses credibility and fails to respond to warning signs. He now faces a simpler but no less serious choice. He can continue to indulge constitutional distractions, electoral experiments, nationalist impulses and internal horse–trading. Or he can call a halt, steady the ship and turn his government back to the basics of protecting people and strengthening institutions.

That means freezing pre–election constitutional and electoral changes, committing publicly to a clean 2026 contest under the existing framework, restoring focus in key sectors like sugar and health, stabilising fiscal management, and treating social crises with the urgency they deserve. It also means resisting the temptation to govern for the comfort of elites — political, traditional or religious — at the expense of those who have the least.

If he chooses the first path, he may preserve a coalition for a time, but he will break the nation. If he chooses the second, he may anger some allies, but he will give Fiji a chance to pull back from the abyss. Fiji does not need grand promises. It needs a captain who understands that when the ship is heading toward rocks, the only responsible act is to change course — now, not after the crash.

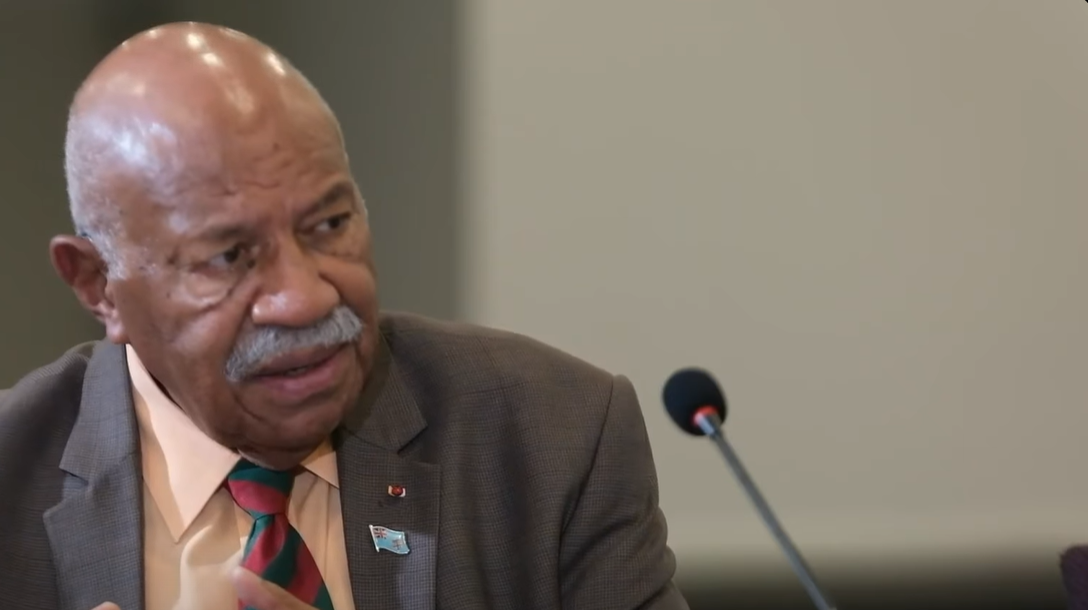

Dr Sushil K Sharma BA MA MEng (RMIT) PhD (Melbourne) is a world World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) accredited Class 1 Professional Meteorologist and former Aviation Meteorologist for the British Aerospace and the Royal Saudi Air Force. Former Associate Professor of Meteorology Fiji National University and manager climate, research and services division Fiji Meteorological Services. The views expressed are that of the author and not necessarily shared by The Fiji Times.