Last week, we discussed how Fiji got annexed by Britain and the key role played by Ratu Seru Cakobau in the process. We said that amid constant skirmishes and battles for territorial dominance and power, Ratu Seru emerged as a central chief, a self-styled Tui Viti, who offered and finally succeeded in getting Fiji ceded to Queen Victoria and the British Crown on October 10, 1874. There was much more at play that needs to be discussed here in our quest to understand better the emergence of and the salient factors that drive and influence contemporary Fijian politics. Let’s focus first on the first Tui Viti.

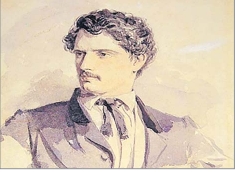

Ratu Seru Cakobau

LAST week I said Ratu Seru had “bestowed (the title of Tui Viti) upon himself”. This came from the common narrative that is freely available. Qasenivuli Paul Geraghty, whom I have deep respect for on matters of Fijian history, culture and language, pointed out to me that this feat was not accomplished as simply as that. Thus, I researched this issue further and wish to add the following for clarity because there are a number of factors that were at play and that inevitably pushed Ratu Seru to hanker for, aspire towards and finally claim that exulted position of Tui Viti albeit briefly (1871-1874).

On December 8, 1852, Ratu Seru Cakobau succeeded to the position of Vunivalu of Bau. His predecessor was his father, Ratu Tanoa Visawaqa. Ratu Tanoa, like his predecessors, was involved in many power struggles with the Roko Tui Bau over the course of almost a century. Those wars moved to Lau, Taveuni, Lomaiviti, etc. The link between Bau and Vuna (my village) are well captured in oral literature. I remember hearing, when I was a child, that the only two chiefs who can wear hats and not bow on the chiefly island of Bau are the Sau kei Vuna and the Sau ni Vanua ko Lau. Those stories are for another narration. Let’s get back to Ratu Seru Cakobau.

Ratu Seru was converted to Christianity by the missionary James Calvert in 1854 (Mennell, 1892). He immediately renounced cannibalism and the effects of this conversion were seen at the conclusion of the Battle of Kaba in 1855 where Cakobau crushed his rivals from Rewa and Bau (Roko Tui Bau) and uncharacteristically spared their lives on the battlefield. The cannibal Cakobau would have ceremonially humiliated, killed and eaten the defeated warriors. He had lost ignominiously and brutally to the same enemy just two years earlier in 1853. This time he was assisted in no small measure by Tongan forces led by the King of Tonga Jiaoji Tupou and Enele Ma’afu who would later sign the Deed of Cession at Cakobau’s side.

Cakobau was obviously adept at organising support from different sources at different times. Coming to the title of Tui Viti, the first mentions we have of this are seen in Calvert’s diaries around 1848. The following entry was made on 19/09/1848: “The Captain (of the Wesley) being short of food — not having provisioned the vessel for so long as he will be likely to remain, desired me to request Tui Feejee to procure some pigs for the ship. I therefore — after the manner of Feejee — presented a piece of print, two large knives, and two large whale’s teeth — and the chief promised to search for pigs”.

I believe, the missionaries who were clearly on a mission were zooming strategically onto chiefs or who they believed to be leaders with power and influence over their tribes/followers. Readers will note that the first Methodist missionaries arrived in 1835. Lau was the first to embrace the new faith with no small influence from its close links with Tonga. Thirteen years later, Cakobau was on the radar. This was also a time when he was intensifying his jockeying for territory and power. What better way was there to get onto his right side than to acknowledge, no matter how subtly or openly, that he was actually the Tui Viti.

After all, flattery can work miracles with ambitious people and especially with those in power. The beachcombers had already mastered this art and were steadily spreading their influence over Fiji. More importantly, Ratu Seru now began to fancy himself as the Tui Viti. Thus, when he became Vunivalu in December 1852, he immediately claimed that Bau had suzerainty over the remainder of Fiji; asserting at the same time that he was the King of Fiji — there is no written record of him actually saying this, but his conduct clearly showed that he saw himself no longer as first among equals.

That was 1852, a long way from 1871 when he finally did acquire that mantle for a short while with the assistance and support of hopeful and ambitious white settlers from Levuka. I wish to throw some light on how Ratu Tanoa (Ratu Seru’s father) acquired the name “Visawaqa” and how Ratu Seru acquired the name “Cakobau”. The research on this and the implications are important for this series.

Visawaqa and Cakobau

I said earlier that every Fijian traces his roots to Lutunasobasoba and the arrival of the Kaunitoni at Vuda near Viseisei Village. It is from here that the legends originate about travels across the Nakauvadra range by selected warriors like Coci who was said to be Degei’s second son. We hear tales of the Rasau, O rau na Ciri (Nakauvadra Twins, Nakausabaria and Cirinakaumoli who are seen on Fiji’s Coat of Arms), Ratu Vueti (said to be a fourth generation descendant of Lutunasobasoba), the Nakauvadra Wars and how Ratu Vueti moved his people towards the sea and made a cairn at Ulunivuaka — this is still there in Bau.

Ratu Vueti took the titles of Roko Tui Bau Vuani-ivi and Koroi Ratu Maibulu (Tukutuku Raraba – History of Bau). Records say that after his death, Ratu Vueti was buried in Kubuna in a throne called Tabukasivi, where he was deified and became the ancestral god of the people of Kubuna. They worshiped him in the form of a serpent; a link to Degei? What is important for this series is that after his death, disputes on his successor arose between the Bucaira and Vunibuca clans. This is where we see the first fractures in Kubuna which have a bearing on the power struggles between the Roko Tui Bau and the Vunivalu.

By 1804 when Naulivou was installed as the Vunivalu after the death of his father Banuve who had three sons Naulivou, Tanoa II and Celua, the Vunivalu had become the highest chiefly title in the Kingdom of Kubuna. The Roko Tui Bau Vuani-ivi at that time was Ratu Raiwalui (the sixth in that lineage). Their wars led to the two sides skirmishing, chasing and fleeing to different parts of Fiji at different times. After one such skirmish, the Vuani-ivi sought the assistance of Titokobitu, the chief of Namara. From there they were joined by some other chiefs of Namara as they continued their journey to Koro and from there to (my village) Vuna in Taveuni.

Part of this group continued to Vanuabalavu, but the rest of the Namara people were left behind in Vuna. Those who continued to Vanuabalavu were largely from the Vuani-ivi who left behind some of their canoes on the beaches of Vuna as the group of travellers was now smaller. Informants led Vunivalu Naulivou to despatch his brother Ratu Tanoa to pursue the Vuani-ivi in Vanuabalavu. Ratu Tanoa, by now, had the use of firearms through Charlie Savage who had been shipwrecked in the Eliza (A History of Fiji, Chpt 4, pp.54-55).

The two groups led by Ratu Tanoa and Ratu Raiwalui met at sea off Mago Island and a fierce battle ensued where the Vuani-ivi lost close to 100 men and their chief, Ratu Raiwalui (Oceania, University of Sydney). Those who fled sought refuge in Vuna on Taveuni. Ratu Tanoa pursued them and after a small struggle set up base in Vuloci according to Wikipedia, but this was probably Vulovi as related through oral tradition. That was where Adi Sugavanua of the Vuaniivi, Vusaratu clan, was offered as a token of peace. She was taken to Bau and became the wife of Naulivou.

Meanwhile, Ratu Tanoa saw the canoes left behind by the Vuani-ivi in Vuna and set fire to them creating a mighty inferno. In the process he acquired the name Tanoa Visawaqa, or Tanoa “The burner of boats (Apologies to the Thucydides, p.249). We’ll see how the name Cakobau was acquired by the Vunivalu in Bau next week. Till then, sa moce toka mada.

n DR SUBHASH APPANNA is a senior USP academic who has been writing regularly on issues of historical and national significance. The views expressed here are his alone and not necessarily shared by this newspaper or his employers subhash.appana@usp.ac.fj