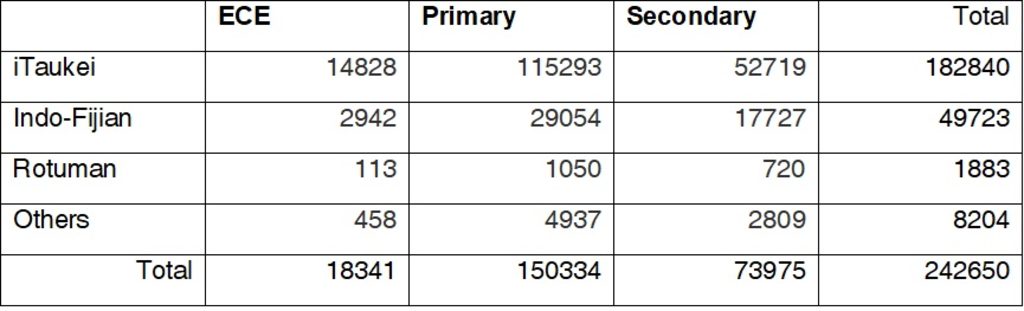

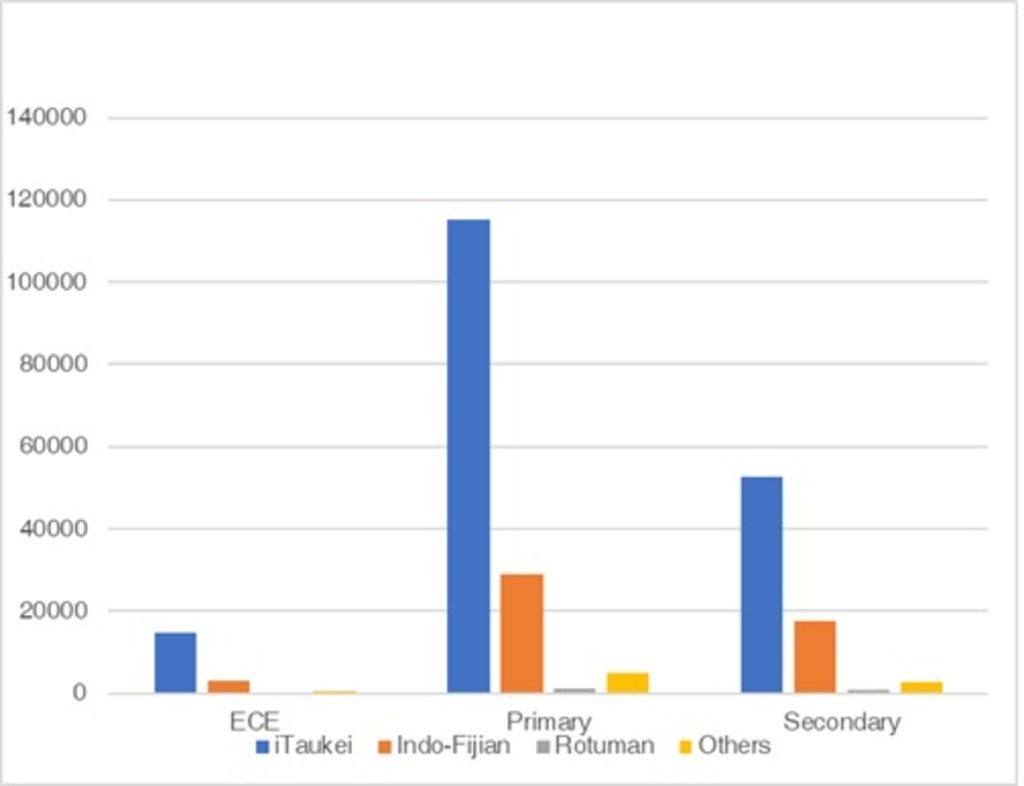

Current school enrolment figures paint a stark picture of Fiji’s demographic future. Out of 242,665 students enrolled in early childhood, primary, and secondary education, 182,840 are iTaukei, while only 49,723 are Indo-Fijian. That means Indo-Fijians now make up just one-fifth of the school-age population, while iTaukei children constitute three-quarters.

The imbalance is especially visible at the youngest levels of education. At the early childhood stage (ECE), only 2942 Indo-Fijian children are enrolled compared with 14,828 iTaukei. In other words, the replacement generation of Indo-Fijians is alarmingly small. This is the result of decades of demographic change. Indo-Fijians have some of the lowest fertility rates in the developing world, combined with sustained outward migration. The school roll is a mirror of what the future will look like: a Fiji where Indo-Fijians are a shrinking minority.

Fertility and migration: The demographic decline

Indo-Fijian families today are much smaller than they were two or three generations ago. Where once large families were the norm, now most Indo-Fijian households have one or two children at most. Economic pressures, urbanisation, and rising aspirations for education have all played their part. But just as important is migration.

Since the coups of 1987, when Indo-Fijians were directly targeted, there has been a steady stream of outmigration to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. The upheavals of 2000 and 2006 and, most recently, the regime change in 2022 only accelerated this trend. Many of Fiji’s best educated and most skilled Indo-Fijians left for opportunities abroad, and their children and grandchildren are now firmly rooted in their adopted countries.

The cumulative effect is that each younger cohort of Indo-Fijians in Fiji is smaller than the one before. A community that once made up half the country is now reduced to barely a third of the total population and among the school-aged, only one in five.

Changing ethnic balance

This demographic reality has profound consequences for Fiji’s politics. For decades, Fijian politics has been framed around ethnic contestation between iTaukei and Indo-Fijians. Elections were fought along communal lines, constitutions were rewritten with ethnicity in mind, and even military coups were justified in the name of “protecting” one community from the other.

But the numbers are shifting the ground beneath this old conflict. Indo-Fijians simply do not have the demographic weight they once had. Their shrinking share of the population means they are less able to influence outcomes through the ballot box, and their political leverage is steadily diminishing.

In theory, this could reduce the perception of an ethnic “threat.” With Indo-Fijians no longer close to parity, there is less fear among iTaukei that their political dominance could be challenged. Yet the danger is that a reduced Indo-Fijian presence will also reduce incentives for power-sharing, compromise, and inclusion. Democracy that relies only on numbers risks degenerating into majoritarianism, where the majority dominates simply because it can.

Historical lessons

Fiji has already experienced the costs of ethnic division. The coups of 1987 were explicitly aimed at preventing Indo-Fijians from holding political power. The violence of 2000 was justified on similar grounds. These upheavals tore apart communities, wrecked the economy, and left scars that still shape the country today.

But the irony is that demographic decline is solving the very “problem” that coup leaders once claimed to address. Indo-Fijians no longer have the numbers to dominate. The danger now is not Indo-Fijian ascendancy, but Indo-Fijian marginalisation.

Comparative perspectives

Other societies offer useful parallels. In Trinidad and Mauritius, for example, Indian-origin populations have remained large and politically influential, ensuring that politics has been multipolar and power has to be shared. Fiji is heading in a different direction. As Indo-Fijians decline both relatively and absolutely, politics risks becoming unipolar, dominated by a single majority.

In such contexts, the protection of minority rights becomes even more important. History shows that where minorities shrink without strong constitutional safeguards, they are often pushed to the margins of national life. Fiji must guard against this outcome.

What the numbers mean for the future

The enrolment data makes it clear that Indo-Fijians will make up a smaller and smaller share of the electorate in the coming decades. Already, their voice is reduced in public debate, their presence shrinking in villages, towns, and schools. Outward migration means that many of the most talented and ambitious Indo-Fijians are now contributing to the economies of other countries, not their homeland.

For Fiji, this has two implications. First, it means that politics cannot continue to be built on ethnic competition because one side of that competition is disappearing.

Second, it means that unless deliberate steps are taken, the Indo-Fijian community may lose not just numbers but also its sense of belonging.

Towards a new social contract

Fiji must now grapple with the challenge of inclusivity in a new way. In the past, the question was how to share power between two large ethnic groups. Today, the challenge is how to ensure that a shrinking minority is not excluded from the life of the nation.

That requires more than platitudes. It means strengthening constitutional protections for minority rights, ensuring fair access to land and resources, and promoting a civic identity that transcends ethnic divisions. It means recognising that the legitimacy of the state does not come from the dominance of one community, but from the trust of all.

Conclusion

The figures in Fiji’s school enrolment data are a warning of what lies ahead. Indo-Fijians are becoming fewer with each passing generation, and outward migration will continue to accelerate this trend. Unless Fiji confronts this reality honestly, it risks sliding into a politics of unchecked dominance and quiet exclusion.

n NILESH LAL is the Executive Director of Dialogue Fiji, a civil society organisation working on strengthening democracy, human rights, and social cohesion in Fiji. A political scientist by training, he writes frequently on governance and development issues in Fiji.

aaa

a