The latest World Obesity Atlas 2023 — yes, there is such a thing — has three important findings for countries globally, including those in the Asia-Pacific region.

First, the prevalence of obesity is rising rapidly, especially in middle income countries and among the young. Second, obesity has very significant – but often avoidable — financial and economic impacts, as well as health impacts.

Third, few low and middle income countries are adequately prepared to respond: for example, Papua New Guinea is ranked 182 out of 183 countries in the world in terms of ‘global preparedness’.

The Atlas reports significant increases in the prevalence of obesity at the global level. It notes, for example, that ‘every country is affected by obesity’ (body mass index or BMI of ≥ 30 kg per metre of height squared) and that no country has reported ‘a decline in obesity prevalence across their entire population, and none are on track to meet the World Health Organization’s (WHO) target of ‘no increase on 2010 levels by 2025’’.

The report goes on to say that 51 per cent, or more than 4 billion people, will be living with either overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) or obesity by 2035 if current trends prevail; 1 in 4 people (nearly 2 billion) will have obesity.

Figure 1 shows the projected increase in numbers, and increased proportion, of the population globally being overweight or obese between 2020 and 2035.

The Atlas emphasises that the largest proportion of obesity globally already occurs in middle income countries.

It estimates that, globally, just on 60 per cent of men and women with obesity lived in middle income countries in 2020, with this share projected to rise to 70 per cent by 2035.

The share living in high income countries falls accordingly. The Atlas also includes projections for the rise in obesity for different geographical regions.

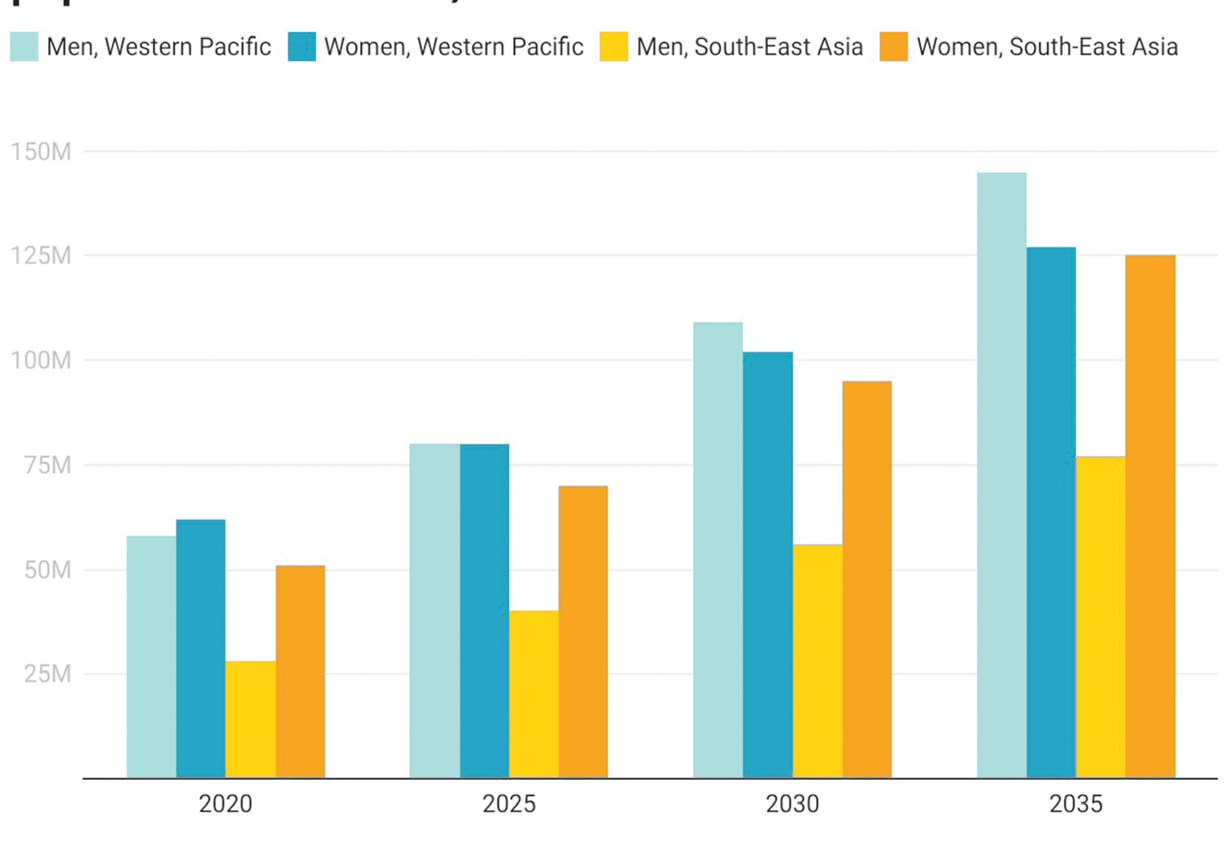

For example, it estimates the total number of adults living with obesity will more than double between 2020 and 2035 in both the WHO Western Pacific region – which includes China but also the Pacific Island countries – as well as the WHO South-East Asia region.

Importantly, the prevalence of obesity (that is, the proportion of the population at a given point in time) is expected to double, on average, for key cohorts over that period as well.

For example, the Atlas estimates the prevalence of obesity in men to increase from 8 per cent of the adult population to 19 per cent in the Western Pacific region, and for women to increase from 8 per to 16 per cent in the South-East Asia region, between 2020 and 2035.

One of the most interesting and useful, but potentially disturbing, parts of the Atlas is the assessment of individual countries’ ‘readiness to cope with the predicted rising levels of obesity, especially in its more severe forms, and the consequential NCDs [noncommunicable diseases] that arise’.

In essence, the report draws on four sources of information to generate a ‘preparedness ranking’ for 183 individual countries for which data is available.

The first source of data is the extent of effective universal health coverage in a country, using the 23 indicators that are tracked as part of the Sustainable Development Goals as at 2019 (latest year available).

The second source of data is the WHO listing of premature deaths due to NCDs as a proportion of all NCD deaths, given the high degree of correlation between obesity and NCDs.

The third source of data is the extent to which a country provides any of 13 NCD-related indicators in the public health system, for example, general availability of diabetes testing and/or total cholesterol measurement at the primary health care level, and general availability of statins in the public health sector.

The fourth source involves data on 12 ‘NCD-related policy-related indicators for the prevention of NCDs at a national level’, including policies to reduce physical inactivity, salt consumption, unhealthy diets, and marketing of unhealthy foods to children.

According to the preparedness rankings for countries in Asia and the Pacific. Switzerland is ranked first out of 183 countries. Within the Asia-Pacific region the Republic of Korea is assessed as being the most prepared, ranked 17 out of 183 countries globally.

Four countries in the region are in the top 34 countries of the world rated as ‘good’. The Atlas uses a traffic light classification with countries rated as ‘fairly good’ (light green), through ‘average’ (yellow), to ‘poor’ (light red) and ‘very poor’ (bright red).

Eight countries in Asia and the Pacific are rated as ‘very poor’. Definitions of the terms used are on page 229 of the report.

There are some worrying scenarios for countries in the Asia- Pacific region. Of concern is that PNG is rated 182 out of 183 countries, that is, the second leastprepared country in the world after Niger, which is ranked last at 183.

This is worrying because the Atlas estimates that the annual increase in adult and child obesity in PNG over the period 2020- 2035 will be, respectively, 2.8 per cent and 5.2 per cent per annum.

That, in turn, implies adults with obesity will be 38 per cent of the population of PNG by 2035.

The Atlas also has projections that by 2035 around two-thirds or more of the adult population will have obesity in a number of countries in the region including the Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Samoa and Tonga.

On a more positive note, the Atlas rates Timor-Leste’s and Sri Lanka’s global preparedness as ‘fairly good’ (ranked 44/183 and 40/183) with adult obesity prevalence of 12 per cent and 14 per cent by 2035 respectively.

As lower middle income countries, Timor-Leste and Sri Lanka may therefore have program and policy lessons for other countries in the region. Identifying those specific lessons would be a useful subject for next year’s edition of the World Obesity Atlas.

• IAN ANDERSON is an associate at the Development Policy Centre. He has a PhD from the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University; over 25 years of experience at AusAID; and since 2011 has been an independent economics consultant.