The early Fijians circumcised their boys around the age of puberty, about the twelfth year.

In the book, The Fijians -A Study of the Decay of Custom, Basil Thomson wrote that during pagan times, this coming of age may have arrived earlier.

Circumcision was not strictly a religious rite. However, it was invested with religious observance of restrictions or tabu.

It was generally performed inside a village bure on about ten or twenty youths by one of the village elders.

A sharp piece of split bamboo was used during the operation. Bleeding during the operation was soaked on a strip of bark cloth, called kula (red).

This plain bark cloth was similar to the long ones that hung from the roof of the burekalou or temple to allow the spirits of the deities to enter the priest.

Upon circumcision, food, mostly green vegetables, was offered to the boys by women.

According to Thomson, in some parts of Fiji, while carrying the food to the bure, women chanted the following words: “Memu wai onkori ka kula; Au solia mai loaloa; Au solia na ndrau ni thevunga; Memu wai onkori ka kula.” This translates to: “Your broth, you, the circumcised; From the darkness I give it; I give you the vunga leaves; Your broth, you, the circumcised.”

The circumcision ritual

The native word for circumcision, teve, was like a taboo word.

It was not mentioned before the presence of women.

If teve was to be uttered in their presence, the word kula was used. As we discovered last week, the proper time for performing the rite was immediately after the death of a chief or certain marked periods, like the flowering of the drala plant. In some parts of Fiji, circumcision was accompanied by an orgy of sorts.

In Thomson’s book, he wrote that circumcision was accompanied by rude games such as “wrestling, sham fights and mimic sieges” which varied depending on localities.

An uncircumcised youth was regarded as unclean, and was not permitted to “carry food for the chiefs”.

After being circumcised, a boy was regarded a young man. He was allowed to wear the malo, or perineal bandage. Children of both sexes went naked until they were ten years old, or even later if they were of high rank.

“The assumption of the malo, or of the liku (grass petticoat) by the child of a chief was the occasion of a great feast, and the postponement of this feast sometimes condemned the child to go naked until long after puberty,” Thomson wrote.

In one of Thomson’s accounts, the daughter of a late chief of Sabeto, was still unclad till past eighteen, which would be unthinkable in today’s world.

The princess was compelled, through modesty, to “keep the house until after nightfall”, Thomson said.

The custom of circumcision still remains today although many rituals have been removed.

Today, young boys are circumcised by a doctor using surgical instruments and in a hygienic environment.

Infections are unheard off, unlike the days of old when many died through infections.

Families get together over a feast on the fourth night after circumcision to celebrate a young boy’s coming of age. A boy’s mum and aunts often spread out the choicest mats for the circumcised boy to sit on during the feast.

Thomson had tried unsuccessfully to understand the origin of circumcision in Fiji.

“The most that a Fijian can say is that to be uncircumcised is a reproach, though to a people who cover the pudenda with the hand even while bathing, and probably never expose their nakedness even to their own sex throughout their lives, this can have but little weight.”

“No doubt the Fijians brought the custom with them in remote times, and its origin is probably the same in their case as in that

of the Nacua of Central America, the Egyptians, and the Bantu races of Africa—namely, the idea of a blood sacrifice to the mysterious spirit of reproduction.”

Girl at puberty

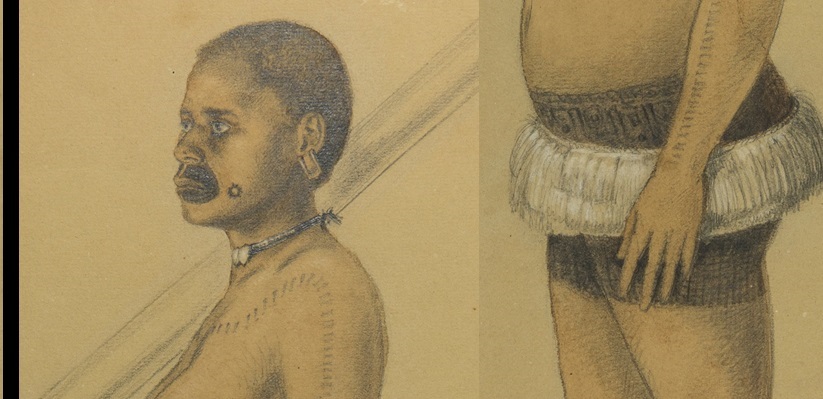

Shortly before puberty every Fijian girl was tattooed. This was not for ornament.

The marks were limited to a broad horizontal band covering those parts that were concealed by a grass skirt called liku.

The tattoos started about an inch below the cleft of the buttocks and ending on the thighs about an inch below the fork of the legs.

“There is not much art in the patterns, which are, as a rule, mere interlacing of parallel line and lozenges, the object being apparently to cover every portion of the skin with pigment,” Thomson said.

The operation was performed by old women. There was often three of them, two to hold the girl, and the third to perform the ritual.

Tattooing was done in the daytime, when the men were busy in their plantations. In some parts of Fiji, special caves called qara ni veiqia, were used to carry out the female initiation.

According to records of the website, veiqiaproject.com, in Ra, Adi Vilaiwasa, the daughter of Degei, was believed to be the fi rst woman to be tattooed.

“She was tattooed in a cave below the sacred summit of the Nakauvadra mountain range in the valley of the upper Wainibuka River in Ra. In 1886 the cave was still used to tattoo women.”

Girls were stripped on the open floor for tattooing, where the light was at its best.

“With an instrument called a mbati, or tooth, and a coconut shell filled with a mixture of charcoal and candle-nut oil, the operator first paints on the lines with a twig, and then drives them home with the mbati, which consists of two or more bone teeth embedded in a wooden handle about six inches long…,” said Thomson.

The artesan dipped the bati in the pigment between each stroke of the mallet, and wiped away the blood with bark-cloth, while the other two controlled the girl’s struggles.

The ritual was painful especially around the tender parts between the thighs. It often caused skin inflammation, but the wounds healed quickly. A ceremonial feast was given by the girl’s parents.

In addition to this tattooing, barbed lines and dots were marked upon the hands and fingers of young girls to advantage when handing food for the chiefs.

After childbirth a semicircular patch was tattooed at each corner of a girl’s mouth.

In the highland districts of Viti Levu these patches were sometimes joined by narrow lines following the curve of both lips.

The motive for this practice was to display publicly on a woman’s body “a badge of matronly staidness and respectability”.

“The wife who has borne children has fulfilled her mission, and she pleases her husband best by ceasing for the remainder of her life to please other men.”

“The tattooing of the buttocks has undoubtedly some hidden sexual significance which is difficult to arrive at. It is said to have been instituted by the god Ndengei (Degei), and in the last journey of the shades an untattooed woman was subjected to various indignities.”

Why were women tattooed?

Thomson said the motive of the girl in submitting to a painful operation was the same as all submission to “grotesque decrees of fashion”. That was the fear of being ridiculed.

If untattooed, a girl became the subject of gossip and teasing. In the worst case, she would have difficulty in finding a husband.

But the reason for the tattooing is unclear. Thomson suspected it must have been the result of sexual superstition.

“When I was endeavouring to obtain some of the ancient chants used in the Nanga celebrations on the Ra coast, I was always assured that the solemn vows of secrecy which bound the initiated not to divulge the mbaki mysteries sealed the lips even of their Christian descendants,” Thomson said.

“I was persuaded either that they had forgotten the chants, or that they considered them unfit for my ears, for it was impossible to believe that the reward I was able to offer would fail to tempt a Fijian to risk offending deities in whom it was evident that he no longer believed.”

Thomson added that a Colo chief once said that besides the other advantages, tattooing was believed to stimulate the sexual passion in the woman herself.

Tattooing tools

According to theveiqiaproject.com, the daubati or tattooist, first painted guidelines on each girl’s body before tapping the desired weniqia (patterns) into the flesh using tattooing tools dipped in soot.

“Tools included pigment typically made from dakua gum soot mixed with a little water, damp bark cloth to wipe up the blood, beater sticks, and tattooing picks, each consisting of gasau reed or duruka cane handle with bone or thorn teeth set at one end at right angles to the shaft,” it noted.

Bone handles were also used.

The pigments, which imparted a dark blue pattern under the skin, were made from soot mixed with oil.

For girls of chiefly rank, the soot was obtained by toasting shelled lauci or sikeci candlenuts over a fire. Sooty smoke was trapped in an overturned pot, the nuts being strung on a sasa or coconut leaf midrib for the purpose.

The sot was then scrapped free and mixed with candlenut oil.

For commoners, the soot was generally obtained by burning the resin from the dakua makadre tree. In some highland districts dye was obtained from the other suitable trees, to replace those used in coastal communities.

In some parts of Fiji girls to be tattooed were required to go without food for 12 hours. They were also required to fetch for freshwater prawns from dusk until dawn and were tasked to look for three lemon thorns to be used on them during the body art ritual.

Before tattooing a prayer to the spirits of the dead was offered to bless the “ink” and tools used during the ritual, as well as softening the skin to make tattooing easier.

When Christianity arrived, the Methodist Mission teachers waged war against heathen customs, among them the tattooing of women.

In some parts of Fiji, keloids or raised scars that adorned the skin of the arms and backs of women.

These scars were caused by repeatedly burning the skin with a firebrand. The burn sore remained open for several weeks and left behind a series of dotted or circular scars once it healed.

Today, both men and women can get tattooed from a tattooist using modern instruments and ink, generally as a fashion statement or body art.

(This article was adapted from records in the book, The Fijians -A Study of the Decay of Custom by Basil Thomson and the website of The Veiqia Project)

- History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor.