MORE than 80 kilometres from Suva, reached only by a winding gravel road that cuts through dense tropical forest and skirts steep mountain ridges, lies Nabukelevu, the furthest village in Colo kei Serua (interior of Serua)

For those who make the journey inland by four-wheel-drive or the three-tonne carriers favoured by villagers, the sense of remoteness quickly becomes immediate.

Nabukelevu sits close to the headwaters of the Navua River, overlooking vast stretches of fertile wetlands that have sustained generations and it is a place spoken of with reverence across the province.

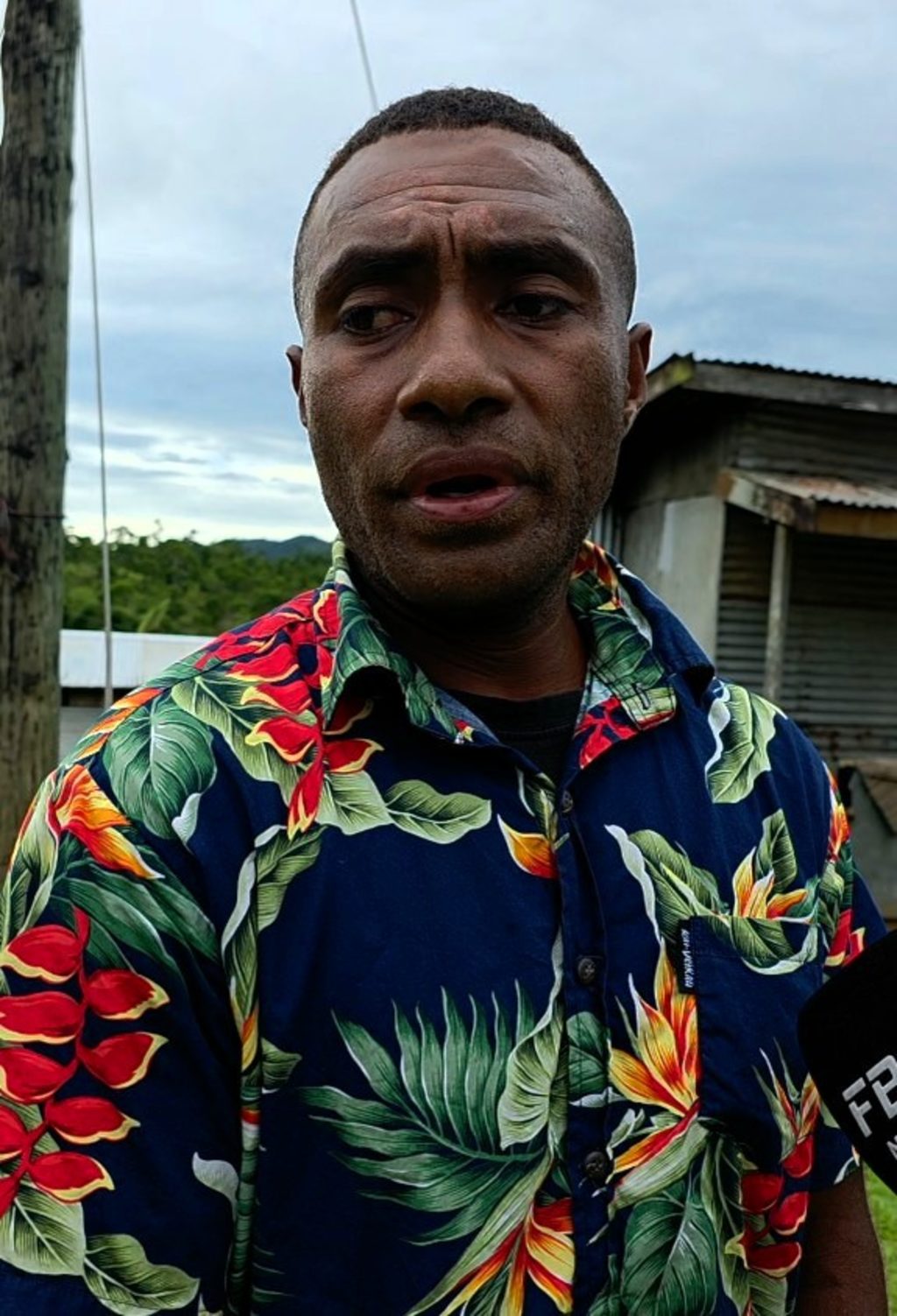

As village headman Mataiasi Toma puts it, there is an old adage that says:”If you have not set foot in Nabukelevu, then you have not truly set foot in Serua.”

It is from this ancestral heartland that a growing resistance to mining and environmentally destructive resource extraction is emerging.

Custodians

Nabukelevu is one of three villages, alongside Naboutini and Nakorovou, that trace their origins to the yavusa Burenitu.

While many families eventually moved outward to establish the other settlements, the forefathers of Nabukelevu chose to remain, enduring hardship to protect the ancestral mound and surrounding lands.

Today, the various mataqali of Nabukelevu and the wider yavusa Burenitu are custodians of hundreds of acres of dense forest.

These lands are rich not only in biodiversity but also in commercially valuable mahogany and, beneath the soil, mineral deposits believed to include gold.

Yet, despite this potential wealth, the message from the village is clear, which is, mining is not welcome.

That position was underscored during a talanoa session held earlier this week at the Nabukelevu Village Hall with the Minister for Environment and Climate Change, Lynda Tabuya.

Representatives from the Serua Provincial Council and government officials were also present.

While the vanua o Serua has not yet issued a formal collective declaration, discussions revealed strong opposition within the yavusa Burenitu to any form of mining in the province.

Learning from Namosi

The stance taken in Nabukelevu mirrors that of neighbouring yavusa Nabukebuke in Namosi, where the Gone Turaga na Vunivalu na Tui Namosi, Ratu Suliano Matanitobua, has made it clear that mining will not proceed until Fiji’s Mining Act is reviewed.

For many in Serua’s interior, Namosi’s position offers both precedent and protection.

“We have come to understand that most of the profits and benefits would end up in the hands of foreigners,” Mr Toma said in an interview with The Sunday Times.

“Very little in terms of development or sustainable livelihoods would remain with us.”

More troubling, he added, is the long-term cost to the environment, which is a price the village and the vanua is unwilling to pay.

Rivers under threat

Nabukelevu is no stranger to the impacts of extractive industries.

Logging has long been a feature of the area, but villagers say the practices employed in recent years have been reckless.

“The biggest challenge facing Nabukelevu today is the conservation and protection of our resources and environment for future generations,” Mr Toma said.

“Unsustainable extraction has severely affected our rivers.”

Deforestation, he explained, has triggered frequent flooding and landslides in places where such events were once rare.

Slopes that held firm for generations have given way, while rivers that once ran clear now swell and overflow with alarming regularity.

Mineral prospecting has only further compounded the damage.

From 2016 to 2023, a foreign company carried out gold prospecting in the area after receiving government approval.

Though exploratory in nature, the work left scars on the land and deepened community unease.

“We realised we did not want a future where our children would only hear stories about our beautiful environment — our rivers and mountains — without ever being able to see them,” Mr Toma said.

The prospecting was halted in 2023, when company representatives recently returned to propose resuming operations, they were met with growing unity and firm resistance from elders and vanua leaders.

“There are now strong calls among our people to oppose any further prospecting, which would eventually lead to mining,” he said.

A question of control

Underlying the opposition is a deeper frustration with the legal framework governing mineral resources in Fiji.

Despite being customary landowners, communities have no legal ownership or control over minerals found beneath their land.

“We recognise that, despite being the land and resource owners, the law gives us no control over minerals,” Mr Toma said. “That is a hard truth for many of our people to accept.”

In this context, resistance becomes not only an environmental stance, but also an assertion of dignity and self-determination.

Roads and resilience

Environmental protection is not the village’s only concern. Access remains a daily challenge.

The road into Nabukelevu, first cut many years ago, has seen little improvement beyond occasional grading.

“Our forefathers used to walk 15 kilometres to Sigatoka and back,” Mr Toma said.

“That shows the hardships our grandparents and parents endured.”

While villagers are grateful that a road now exists, they say it urgently requires major upgrading, particularly as climate change brings heavier rains and further erosion.

Still, hardship is accepted as part of life in the interior.

“Challenges are part and parcel of life,” Mr Toma said.

“We are born into this world to face challenges, and without these tests, we cannot build a better life.”

Looking to the next generation

Beyond land and infrastructure, Nabukelevu’s leaders are also worried about social challenges, particularly the global spread of drugs and its impact on youth.

“This is not just a village problem, it is a global one,” Mr Toma said.

“Government, the vanua and the church must work together with a shared purpose.”

For him, the solution begins at home: listening to young people, guiding them, and meeting them at their level.

“If we do not care for our youth now,” he warned, “we worry about what the situation may look like in 20 years.”

While the affairs at Nabukelevu to many may seen far from Fiji’s geographic and political margins, the choices being made by the vanua there speaks to a national debate about development, ownership and what the true cost of progress really is.

The lush highlights of Serua are home to valuable mahogany trees. Picture: ALIFERETI SAKIASI

A portion of the road leading up to Nabukelevu Village and the interior of Serua.

Picture: ALIFERETI SAKIASI

Nabukelevu village headman, Mataiasi Toma.

Picture: ALIFERETI SAKIASI