I have never written to our President before (or anyone else’s president for that matter).

So, it was with some solemnity that on July 3 last week I pressed ‘send’ on my very first email to His Excellency Ratu Naiqama Lalababalavu. I also copied Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka.

I wanted to tell the President that there seemed to be mistakes in the Commission of Inquiry Report that suggested, at the very least, the authors had been sloppy and not entirely above board about a few things.

As I said to the President, there may be a straightforward explanation. If so, my email may mean this was a fuss over nothing. But on its face, this seemed to me to be a serious matter.

The Commission of Inquiry was created on October 31 last year by then President Ratu Wiliame Katonivere, on the advice of the Prime Minister.

The findings of the COI Report were, supposedly, such a shock to the PM that we are led to believe he saw fit immediately to fire his Attorney-General by Viber message; and then, between the PM and the President, the FICAC Commissioner Barbara Malimali as well [although it’s not clear who made that call].

It had been the circumstances surrounding Ms Malimali’s hiring in September last year that the COI had been set up to investigate.

In addition to the turmoil caused in the life of former A-G Graham Leung and Ms Malimali, the COI Report named nine people that Justice David Ashton-Lewis and the counsel assisting him, Janet Mason, said should be interviewed by police on a range of possible charges including perjury, perverting and/or obstructing the course of justice.

One of the things that Justice Ashton-Lewis, who sits on the Fiji Supreme Court, alleged repeatedly were that lies, untruths and forgeries helped bring to life a plot to shunt Ms Malimali at lightning speed into the FICAC Commissioner’s office. This was the audacious conspiracy which would enable her “to do evil peoples’ designs’, he claimed to listeners of Radio 4CRB of Queensland in a now infamous interview in May.

But Justice Ashton-Lewis – or Ms Mason or someone – also has some questions to answer about the “document integrity” of his own report.

‘Document integrity’ means the water-tight assurance that any document at the centre of a legal case has remained complete, accurate, and unaltered since its creation or initial approval, right through the remaining steps of the legal process. This could relate to anything from a passport to a land title, mortgage deed or employment contract, or, in this case, the production of the written report of a judge-led inquiry.

Document integrity is the paperwork equivalent of the ‘chain of custody’ in criminal evidence. If there is a break in that chain, then the process has no integrity. Then prosecutions collapse, and jurors are invited to draw their own conclusion about the reliability of the evidence put forward.

This was one of the most compelling reasons that OJ Simpson was found not guilty in 1995 of the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ron Goldman the year before.

Simpson’s defence team argued that the mishandling and delays in logging evidence, such as blood samples and a crucial fingerprint, showed not only how flawed the forensic case was but how their client could have been framed. An LAPD detective testified he had drawn 8mL of Simpson’s blood for testing, but his paperwork showed he could only account for 6mL.

Before the internet, social media, Photoshop and Artificial Intelligence, document integrity was less of a major concern. After all, you needed to be a master forger, or to have the services of one, to pull off a credible fake document that would survive being tested in court.

But with today’s technology, creating believable fakes has never been more accessible – faster or cheaper – so document integrity has never been more important.

Document integrity and the COI

On July 1, after eight weeks of vexing on the subject, the PM ordered the publication of the COI Report that he had received on May 1, along with the President.

It was a classic ‘Only in Fiji’ moment: everyone already knew what the released document would say. Leaked versions of the COI Report had started to circulate via email and social media around two weeks beforehand.

Here is where document integrity is important.

Surprisingly, right from when those leaked versions started to appear around June 16-17, it was clear there were two different versions. And we know these came from two sources.

One version appears to have originated from New Zealand. It’s not possible to know who was first responsible for this.

But we do know that on June 17, Rajendra Chaudhry, son of the Fiji Labour Party leader, a New Zealand lawyer [and ‘fugitive from justice’ as he was apparently called by Chief Justice Salesi Temo during the COI] shared the executive summary of the COI Report on his social media feed.

Chaudhry Junior had secured a plum position within the COI operation as the appointed legal ‘next friend’ of so-called activist Alexandra Forwood, whose three written allegations to FICAC triggered their investigation of Ms Malimali.

A ‘next friend’ is usually appointed because someone is incapable of representing themselves in a legal case because of ill health, incapacity or because they lack the mental faculties. Mr Chaudhry, on the other hand, became Ms Forwood’s ‘next friend’ because he was incapable of showing the COI that he could be her lawyer. He seems not to be able to get a Fiji practising certificate, meaning he can’t practise law in Fiji.

If you’ve read part or all the COI Report, this New Zealand version is probably what you have read. It’s the most widely distributed one, and is the basis of the ‘heyzine.com’ flipbook available online.

The other version of the COI Report seems to have come via the PM’s Office.

Copies of this version were sent to some of those named in the COI Report as suspected of criminality by Justice Ashton-Lewis. These were ministers and MPs in the PM’s own government as well as senior civil servants. I understand that these copies were made available so that these people could prepare to respond to the COI Report findings.

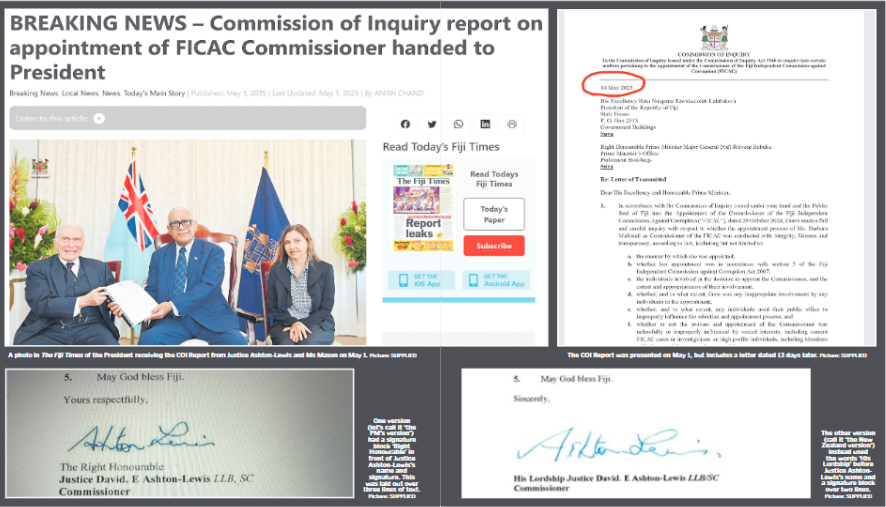

The two versions of the COI Report could be distinguished by at least four observable differences in Justice Ashton-Lewis’s ‘Letter of Transmittal’ (that’s the covering letter that he sent to the President inside the report) and which make up the first and second pages of the bound document:

• one version (let’s call it ‘the PM’s version’) had a signature block ‘Right Honourable’ in front of Justice Ashton-Lewis’s name and signature. This was laid out over three lines of text

• the other version (call it ‘the New Zealand version’) instead used the words ‘His Lordship’ before Justice Ashton-Lewis’s name and a signature block over two lines.

Then there is the question of Justice Ashton-Lewis’s ‘post-nominals’ (an elegant way of describing the letters after his name):

• one version had these written as “LLB/SC”

• the other “LLB, SC”

Both versions also had obvious and significant differences in Justice Ashton-Lewis’s blue-ink signature.

So, four clear differences.

The date on both Letters of Transmittal is the same: May 14.

May 14 is a big day in Fiji’s history (think balaclavas and Sam Thompson’s shaky voice broadcasting live on FM96) but put that aside and think about what May 14, 2025 must mean in this process.

Thirteen days late?

Are you sure the Letter of Transmittal says May 14? Because that doesn’t make sense. This is one of the things I asked the President.

More specifically I pointed out to the President that May 1 was the date printed on the front cover of the COI Report. There’s a photo in The Fiji Times of the President receiving the COI Report from Justice Ashton-Lewis and Ms Mason on May 1.

The COI term authorised by the President ended the next day, on May 2, and Justice Ashton-Lewis told Radio 4CRB he left Fiji on May 11.

So how is a Letter of Transmittal dated May 14 bound into the COI Report dated and delivered to the President on May 1 – 13 days earlier?

Once you see in plain sight that there are two different versions of the May 14 Letter of Transmittal, other urgent questions follow.

Such as: Were any other changes made to the COI Report, given that we can see clearly at least the first two pages of the COI Report have been clearly altered after the date of publication? And if this happened, who knew about it? How did this happen? What was being changed and why?

We can’t turn to the Government Printer for answers. The Government Printer didn’t print it. The COI Report was printed in strict secrecy somewhere else. The identity of the printer is not acknowledged in the report.

The Prime Minister’s decision on July 1 to release the COI Report gave us the opportunity to see which version his Government was now saying was the official version.

The PM’s Office released the ‘His Lordship’ version – the ‘New Zealand’ version.

The ‘Right Honourable’ version, that the PM appeared to share in private in mid-June with selected people, appears to have gone to the dustbin of history.

It’s not clear why one version was selected over another. If this was a court of law, you’d want to run a word check software programme over the soft copy of the almost-700 pages of the two different versions to identify whether any other changes had been made.

As I wrote to the President: ‘As best as I can deduce, the COI Report would appear to have clearly been manipulated ‘after the fact’ with the insertion of at least two post-dated Letters of Transmittal, and the deletion of the May 1-dated Letter of Transmittal. This has potentially grave legal consequences as I am sure Your Excellency can well understand.’

This is not the only beef that I have with the COI Report. But it is the strangest issue that I have, the hardest to find an explanation for and, because it clearly involves serious document integrity concerns, perhaps the most consequential.

I am still waiting for a reply from the President’s Office.