First of all, I pay my deepest respects to traditional owners of lands on which we are meeting. I acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander elders, chiefs – past, present and emerging. Thank you.

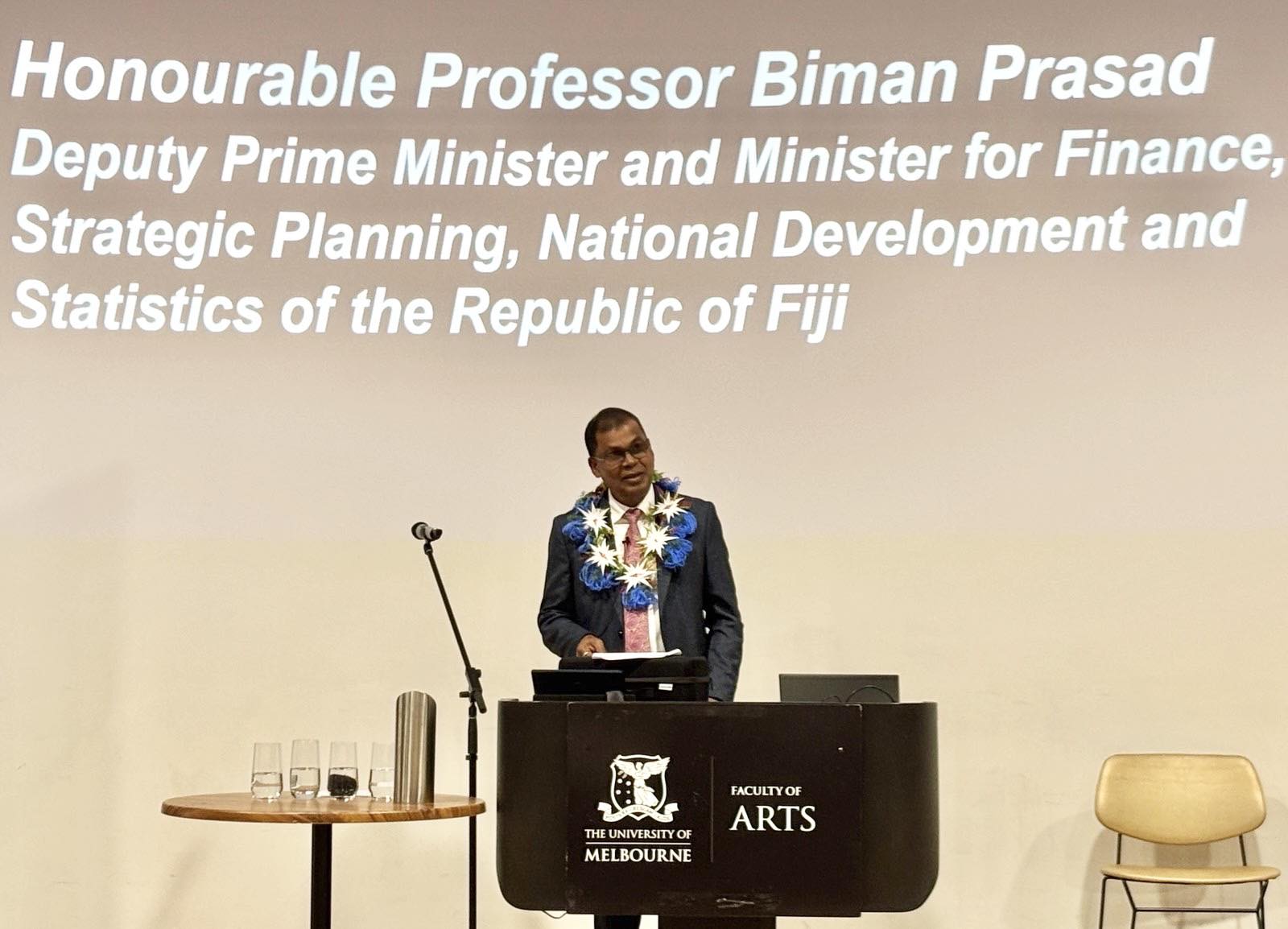

I am deeply honoured to be invited to deliver Oceania Institute’s Inaugural Oceania Oration. I wish the Oceania Institute the greatest of success.

Forgive me for beginning with a longish quote from my great friend, colleague and our elder, the Late Prof. Epeli Ha’oufa:

… if we look at the traditions and cosmologies of the peoples of Ocean, it becomes evident that they did not conceive of their World through a “perceived smallness. Their world was anything but tiny … smallness is a state of mind.

There is a world of difference between viewing the Pacific as ‘islands in a far sea’ and as a ‘sea of islands’. The first (suggests) dry surfaces in a vast ocean far from the centres of power. Focussing in this way stresses the smallness and remoteness of the islands. The second is a more wholistic perspective in which things are seen in the totality of their relationships.

The difference between the two perspectives is reflected in the two terms most often used for our region – Pacific Islands and Oceania. The first term, Pacific Islands .. denotes small areas of land (across vast seas). Oceania (the term you are using) denotes a sea of islands with their inhabitants .. people raised in it were at home in the sea, navigating it and traversing the large gaps that separated their island groups.

The Late Prof Epeli Hau’ofa from our Sea of Islands.

From Oceania to the Blue Pacific

THE late Epeli’s conception of “Oceania” continues to evolve – as it must. We are beginning to see greater acceptance of the term Indo-Pacific. The term Indo-Pacific once again denotes our smallness. The Indo-Pacific has evolved in distant capitals. Indo-Pacific seeks to present Oceania wholly in geostrategic terms – as a vast undifferentiated geography to be dominated; to be managed. It denies our agency. I reject this term.

The term Blue Pacific reclaims our agency. It re-states our collective stewardship over our geography. Blue Pacific places our identity and our sovereignty at the heart of its framing. Equally, it expresses our confidence in engaging with the external world on our terms.

The world has delivered to the Blue Pacific one of the cruellest prognosis – a climate changed Blue Pacific with existential consequences. We will not allow that be our story. Ours is a story of resilience. Our story of resilience will be scripted on peace. I present some of its outlines this evening.

A Pacific-Australia

Faculty, students and invited guests.

I am often asked by Australian media about Australia’s engagement with the Pacific. Allow me to share a few thoughts here.

Australia’s nearly 4000 kilometres of Eastern coastline is where the Blue Pacific finds land at its Western edges. Only 5 miles separates Australia from PNG – the biodiversity and oceanic heartland of the Blue Pacific.

Close to 100,000 of your citizens are born in Samoa or who claim Samoan ancestry. This is roughly equivalent to 50 per cent of Samoa’s population. Over 100,000 Australians of Fijian birth or ancestry live across Melbourne and other cities. That is well over 10 per cent of our own population. All Pacific Islands are well represented here. Australia is their second home. The Pacific Islands is their first.

We watch how Australia and Tuvalu’s Falepili Union evolves. It is possible that in time, a majority of Tuvalu’s population may come live in Australia. This will hardly be a new phenomenon. The overseas populations of Cook Islanders and Niuean’s are already higher by many multiples than their home country populations.

We are delighted at how Australia is changing. Growingly Australians do wake up to a PNG coffee or to a Vanuatu hot chocolate; or to having a Solomon Islands canned tuna snack for lunch, or a Tongan vanilla flavoured ice for dessert. If this does not describe your day, you have a lot of catching up to do.

I am a politician these days. I dare not get into politically explosive sporting zone. I withhold comments about Pacific islanders in your AFL, Melbourne Storm, Box Hill and other teams and on their contributions to your teams sporting greatness.

A Pacific-Australia is a long-settled question for Pacific islanders. I hope that in time this will be a well settled question within Australia.

There are three considerations I advance this evening. The island states of the Pacific are the most climate vulnerable in the World. That you know too well.

Between 2025 and 2030, the annual adaptation cost alone for the Blue Pacific will be in the range of $5 billon (AUD). This harsh reality contrasts with another harsher reality. The total annual grant-based climate finance flows into this region is well below $250 million AUD – barely 5 per cent of what is needed.

Having said that, across Fiji and the region you will see considerable progress in our human development. But we know equally that poverty in urban, rural areas and outer islands remains challenging – most visibly across the Melanesian sub-region. Many of our region’s health indicators are deteriorating. Gender violence is wickedly high. Violent crime and drugs are growing threats to our overall development progress.

The reversals in our human and economic development arising from earthquakes, volcanoes and other hazards are worrisome. The compounding costs of repeated recoveries means that the next recovery becomes infinitely harder than the one preceding it.

We are making determined progress in spite of these. But in the art of development – there are no marks for trying. Far too many lives and livelihoods are impacted when you fail.

This is exemplified nowhere better than in Vanuatu where the combined cost of recovery from its Cyclones Judy and Kevin (of $800 million AUD) and earthquake (of $400 million AUD) adds up to around 90 per cent of its GDP. On their own these may be meaningless numbers to an Australian audience. Allow me to give some personal context to this.

Let me transpose Vanuatu’s recent trajectory onto Australia’s. This would have meant that Australia would have wiped out $1.6 trillion off its $1.8 trillion economy – over a space of 3 days within the past 15 months.

Or at a personal level, imagine if your monthly PhD student scholarship of $4000 were reduced to $400 for the next three years. Rents, electricity, phone bills still have to be paid.

I give this analogy not as a sound byte. I offer this to seek your deep understanding.

I am a finance minister. I know in a personal way how hard it is for small economies to find resources in our budgets for recovery and rebuilding. I know how hard it is to borrow following catastrophes.

It takes decades to recover from the “quiet and often invisible” human development toll of climate change. This is why I have referred to climate catastrophes as having the “cruellest” of impacts on our peoples and on our societies.

The scale of climate catastrophes we bear almost always ends up with a decade or more of “ruptured” development. This will always mean that their Government’s will undertake a period of fiscal prioritisation on steroids. Too many businesses will simply not rise again. Too many jobs will be lost permanently. The scars will be felt over a long time.

The scale of economic and human development challenges means that small island states will continue to require significant support from our development partners.

I know there is a lot of talk about the World entering an era of “end of development assistance” or the end of aid. Yes – the dramatic reductions in international development assistance at this time are exceptionally painful.

International development for PSIDS

International development assistance will remain a crucial part of the international architecture. Granted we all need to work in a more determined way on the TV screens of families in Melbourne, Tokyo, London and Florida to help change perceptions about international development assistance.

There is absolutely no contradiction between helping to reduce poverty in Suva and Moresby and strengthening security in Australia. None whatsoever.

Securing a stable and prosperous Blue Pacific may indeed be one of the single most important ways in which security of Australia can be advanced. This may be as powerful as investments in AUKUS or any other security hardware.

I hope you will agree with me that the architecture of international development and finance has to be transformed. The Blue Pacific’s Finance Ministers are unanimous on this. That time has come.

(i) An international development system designed for the post 2nd World War context is crying to give real voice in decision making to small island states – at the IMF – at the World Bank and across all parts of the global system. Sadly, this is not within our gift.

(ii) The global system of development finance needs to bring to its beating heart the climate-elevated vulnerabilities of small island states when framing decisions about the cost of finance, the length of loans and the volumes of development finance that small island states can secure.

(iii) International institutions must open pathways for substantial debt relief.

Thirdly, the Blue Pacific confronts a woefully expanding infrastructure deficit.

The Blue Pacific’s infrastructure distress is a combined consequence of fiscal stress, climate stress and disaster stress – a lethal cocktail.

Something has to give when faced with cycles of repeated recovery. Most often it will mean that schools and heath centres fall into disrepair and roads unmaintained. Scarce development resources have to be redeployed to preserve frontline services.

The Pacific’s infrastructure deficit can also be seen as “connectivity deficit”. Farmers disconnected from markets when roads fall into disrepair. Women disconnected from healthcare when transportation costs increase. Children disconnected from schools when bridges are washed away.

The Pacific needs a “moonshot” to overcome its infrastructure distress.

The Blue Pacific’s infrastructure needs will be between $6-8 billion AUD annually for the remainder of this decade. The total financial flows into the region through a combination of loans and grants is still barely above the $1 billion mark. That infrastructure financing gap is the “gap of hope”.

I also want to make another broader point. I know Australians will understand this intimately. The Pacific’s infrastructure costs are extraordinarily high. It is not because we are corrupt. It is not because our capacity is low.

The cost of building a road in Broken Hill or Burketown will be higher per kilometre than in Rowville or Epping – always.

It is exactly the same for the Pacific. The cost of a kilometre of road on our southern most island of Kadavu will be 5-7 times higher than in capital Suva. Equipment has to be shipped. Raw materials have to be shipped. There are no local contractors.

And if that were not enough of a hurdle, we need to make all infrastructure climate resilient to meet a climate-changed future that has already arrived. This can add an additional 10 to 70 per cent to the underlying costs of infrastructure.

Let me now cover 3 key issues on which I wanted to draw your attention.

A Climate-changed future

Climate change is the gravest threat to Blue Pacific. At Melbourne University you are at the cutting edge of climate science. You do not need a reminder from me about why 1.5 Celsius goal matters so much. You are at the cutting edge of international law. You do not need the International Court of Justice to tell you how this matters.

The Blue Pacific is undertaking sustained measures to adapt. The missing piece is climate finance. The scale and speed of climate finance will decide whether we can bend the arc of possibilities towards resilience and justice.

As a region, we have consistently presented our case that climate finance should be pre-positioned; climate finance should be predictable; climate finance should be accessible, and climate finance should be on scale.

Our mitigation, adaptation and climate-induced loss and damage needs are growing. The window for adaptation is short – in many cases perhaps a decade and not much longer.

The establishment of Loss and Damage Fund – the vital third pillar of the climate financing regime was a significant step forward. This important new fund continues to struggle to secure the long-term financing.

The risks arising from climate change are so comprehensive, so multi-faceted, and so severe that the Pacific’s economic, social, and political stability can be harmed irreparably.

The interplay of conflicts over land lost to rising seas, stresses arising from urban drift that is fuelled by loss of rural livelihoods, the relentless strain on health and water infrastructure and deepening fiscal stress can make states fragile. The Blue Pacific as a string of highly fragile states is not an impossible proposition.

The link between climate change acceleration and increased state fragility is clear. Let there be no illusions about this. We are profoundly concerned about this. You should be as well.

Will an Australia-Pacific UN Climate Conference COP31 be a circuit breaker moment?

Guests, students and faculty.

It is with much excitement that the Blue Pacific family supports Australia’s bid to host COP31. A COP in our region can be the circuit breaker moment that we desire.

COP31 in Australia will be a moment for those with most power in the World to listen to those with least power – that is, communities from the World’s most climate vulnerable region.

COP31 in Australia will be a forceful moment for Pacific islanders to share our stories of displacement, of building resilience with so little and directly make their case to Australia and the World to deliver on their duty.

Inside and well beyond the negotiation rooms, the Blue Pacific’s civil society, its women and its young will be framing solutions and seeking support for these. Success at COP31 may include:

(i) Securing a fully funded Pacific Regional Infrastructure Facility (PRIF) – our home-grown financial instrument to build our resilience.

(ii) A predictable and disbursement ready Loss and Damage Fund that has moved well into its fully operational phase.

(iii) A global endorsement of the Blue Pacific as an Ocean of Peace anchored to the highest standards of sustainability.

(iv) An Adelaide consensus that all climate finance gateways – at the GCF, in MDB’s and in bilateral development assistance will have ringfenced, targeted and tailored support for small island states.

(v) Support for a transformative regional programme of global significance that seeks to advance marine protection in an interconnected way and build sustainability across the Blue Pacific Ocean.

(vi) An unambiguous statement on predictability, increased speed and increased volume of climate and ocean finance that will be available to small states for the remainder of the decade.

(vii) Secured resources that will flow to communities and families on the Blue Pacific’s frontlines to rapidly build their resilience using the best of their traditional wisdom and knowledge.

Our broader messages remain as consistent as ever. The era of fossil fuels is our past. The era of renewables is our future. How speedily China, Australia, Japan, India, the EU and the World make this transition matters to all of you. It matters for the Blue Pacific even more.

The raging forest fires in Spain, Portugal and Canada today; the nearly $100 billion AUD damage tag from the Texas floods a few weeks back, the hundreds of deaths triggered by Europe’s heatwaves and the oceanic heatwaves wreaking havoc across the Great Barrier and the south seas of Australia today speak to urgency.

The 1.5 Celsius goal is the Pacific’s guardrail. The ICJ has been unambiguous that these are indeed the planet’s guardrails. There are consequences if we cannot get back to a net zero by 2050. We know that the economic and health consequences of this will be far too high for the Blue Pacific. We know as well that there will be massive consequences for Australia.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I now turn to Fiji and Blue Pacific’s proposals for an Ocean of Peace

From an Arc of Instability to An Ocean of Peace

Fiji’s Prime Minister, Hon Sitiveni Rabuka has introduced to the PIF family our proposals for the Blue Pacific to be an Ocean of Peace. And I quote him..

As a region, we know the value of peace. The ocean and its diverse and vibrant lands have been a theatre of two World Wars, a testing ground for the World’s most dangerous weapons … We are not a passive region without agency; the collective voice of the Pacific is as loud as is profound and proud….. The concept of peace comes from deep within our faith in the God of peace, deference and justice.

The Ocean of Peace is one of the most far-reaching advance in our regional framing in a generation. “Humility, quiet leadership, reconciliation and communication” is how we intend to build our peace. The “Pacific Way” is how we will work through our differences.

Our elevated security concerns arise from geostrategic considerations where mis-steps have become entirely feasible. Our urgency arises from that fact that the Blue Pacific has become the centre stage of that geostrategic contestation. Our purpose arises from our belief that peace is the most important strategic investment needed to advance our human development.

Peace across the Blue Pacific matters to us. Of course. Equally, it matters to Australia.

Fiji has proposed to Pacific’s leaders its outline of the Ocean of Peace. This outline includes

- A recognition of our stewardship of our marine environment that is anchored to the highest possible principles of protection and conservation.

- Reaffirming the Blue Pacific’s deep faith in multilateralism as the way forward for finding solutions to conflicts.

- Restating our recognition of international rules that guide freedom of navigation and that promotes peace and security across nearly 40 million square kilometres of the Blue Pacific.

- Elevating our foundational commitment through our 2050 strategy and the Boe Declaration for maintaining peace and security.

Let me expand on two elements related to both framing and eventually the implementation of the core ideas underpinning the Ocean of Peace. These are

- the PIF may call on the international community to refrain from actions that undermine peace and security in the region. This may include ending the militarisation of supply chains and ending securitizing of development assistance.

- The PIF may advance regional economic connectivity and integration across the Blue Pacific in ways that are fundamentally transformative.

Pacific’s leaders will consider these in Honiara in two weeks.

I have no doubt that we will have a new regional consensus on the fundamentally transformative idea of the Blue Pacific as an Ocean of Peace. People who live and traverse these spaces yearn for a sense of security that has been denied to them by history. They stand ready to undertake long term investments that builds a future where opportunity is grounded to our own ideas about peace.

The potential to unleash opportunities for people and communities of a peaceful rather than a restless Blue Pacific are infinite. We need a new framework where threats to sovereignty, economic functionality, and environmental integrity are overcome through systematic cooperation – including between superpowers of our times.

(i) An Ocean of Peace will commit us to investing in our own efforts to build peace at all levels and to resolve conflicts.

(ii) An Ocean of Peace will power progress on regional economic connectivity and enhance regional trade.

(iii) As Ocean of Peace will have its outer maritime boarders better defined and better protected.

(iv) Our fuller economic integration will promote freer movement of people, skills and businesses without restrictive visa regimes.

(v) An Ocean of Peace will fire up the Pacific’s ability to take forward transboundary efforts in marine research, expand opportunities arising from the new Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Treaty, end plastic and other pollution and advance decarbonisation of regional shipping.

(vi) An Ocean of Peace will lay and build firmer foundations for resolving inter-state differences on questions like seabed mining, benefit sharing on BBNJ and on transnational crime.

(vii) An Ocean of Peace will be our building block for main-framing the ocean-climate nexus into the international climate change frameworks at COP31.

(viii) On Ocean of Peace will allow us to take collective approaches to integrating ocean accounting, to managing blue carbon and securing a highly managed approach to the full 100 percent of our seas.

(ix) An economically integrated Ocean of Peace will help us to build capabilities for Blue Finance including through the development of the Pacific’s own regional development bank – a Blue Bank.

(x) An Ocean of Peace will fuel an expansion of sustainable Pacific owned and driven blue economy businesses – the next frontier of Pacific’s growth story.

(xi) An Ocean of Peace will expand and secure spaces for Pacific’s women to lead and build peace and to be an equal part of its commerce.

(xii) An Ocean of Peace will take away the pressures so that we are focussed on reinforcing our governance and accountability institutions nationally and regionally.

That journey will be hard. We know that. Our 2050 strategy for the region is our North Star. An Ocean of Peace is a vision we share deeply. This is a vision that we hope Australia’s vast civil society, its research community, its Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander communities and its industry will share equally.

Securing our future

Fiji’s Prime Minister was unequivocal when he said that our region will need to get better at securing the Blue Pacific. We will need to lead if others are to follow.

Last week we saw the launch of Fiji’s national security strategy. This elevates our security partnership with Australia. Last week you also saw the commissioning of the dual use port on Manus Island – one of the largest maritime infrastructure investments by Australia. In the same week you saw the conclusion of the Australia-Vanuatu “Nakamel” Partnership.

All these reflect a deepening of Australia’s Blue Pacific identity. Australia is not some distant partner in this region. It is the Pacific. It is us.

On the security of the Blue Pacific rests our shared well being – yours and ours.

The centre of world’s power, its economy and its vitality has moved to Asia. This will remain so for the next Century. Australia finds itself beautifully positioned at its centre. A Blue Pacific that is at peace – rather than restless as an “an arc of instability” will be a crucial foundation on which Australia’s prosperity and its security will rest for this Century.

Grounding our partnership to knowledge and learning

I return to this moment. You have chosen a moment for this inaugural talk that could not be harder conceptualise. Our World faces challenges like never before. In fact, perhaps not since the end of the Second World War have we faced such a toxic mix of security, development and political challenges.

Your work at the Oceania Institute and the University is well cut out. I wish you well in providing deeper understanding and analysis of the challenges, risks and opportunities that Australia and the Pacific face at this volatile moment in our history.

A defining feature of Australia’s Pacific future will be the further integration on education. One of the earliest proponents of an integrated education framework across our region, my teacher and mentor Professor Wadan Narsey is present here today.

The pathways and the futures that Australia’s sustained investments in education opens up across the Blue Pacific are immeasurable. I know this in a deeply personal way as well.

It is inconceivable that I would be delivering this lecture to you today had it not been for Australia’s support for my graduate studies at the University of Queensland and UNSW – inconceivable and impossible.

Let me pause to offer my sincerest thanks to Australia’s taxpayers and its government for making my journey possible. On behalf of a deeply grateful Pacific, and on behalf of tens of thousands of Australia Award alumni across the Blue Pacific I offer a heartfelt Vinakavakalevu, Malo ‘aupito, Tanggio tumas, Dhanyavaad.

To the Institute and the University, I hope you will work to build genuine partnerships with USP, UPNG and other regional universities. I hope that you will genuinely co-create research and build shared learning.

I cannot over-emphasize the value that decolonisation of knowledge will bring to building Blue Pacific’s resilience and security.

Ours are oral traditions. That means that our traditional and indigenous knowledge locked in our oral histories and our stories will remain well beyond the reach of our AI algorithms. We comprise less than 1 percent of the World’s population. Yet we own nearly 20 percent of the World’s languages.

As a region, we are building a resilience that we must own. We are writing a chapter of our great history that must finally be ours. The Blue Pacific’s knowledge: its voices and its research must have primacy in our efforts.

I conclude by paraphrasing the Late Epeli Hau’ofa “We are not small islands in a vast ocean – we are the vastness itself”. Reclaiming this “primacy” is reclaiming our vastness.

For scholars at the Oceania institute, I have laid before you our vision of a peaceful and sustainable Blue Pacific. I wish you great success in supporting us to realise our vision.