THOUSANDS of years before the arrival of the first group of explorers, traders and settlers to our shores, indigenous seafarers ruled one of the largest and untouched frontier on earth – the Pacific Ocean.

These fearless sailors and sea-going warriors explored the marine world around them, traded food and goods and engaged in endless battles, many of which influenced the course of Pacific and Fijian history that we know today.

But amongst the many things that helped shape civilisation in Oceania was the capability of the mighty double-hulled drua, the finest sea-going vessels ever designed, built and driven by Pacific Islanders.

The drua’s superior design and speed did not come by chance.

To bring them to life required great understanding of the sea, weather, climatic conditions, and elements of nature like the tides, lunar cycles, winds and the stars.

Furthermore, it also hinged on superb craftsmanship and skills passed down by word of mouth through countless generations.

Fiji sea crafts, the biggest of which were the drua, were of varying sizes, design and purpose yet they all stirred the imagination of sailors from all over the globe.

In Fiji and the Fijians, writer Thomas Williams noted there were four main types of these canoes – the velovelo or takia, camakau, tabilai and drua.

All were differed in the modification of their cama and hull.

Because tribal warfare was rampant at the time, the drua was inevitably fashioned with this disturbing reality in mind.

Invading warriors travelled vast distances to wage war and extend their dominions. To do this, their mode of transport had to be one of the best hands could build.

An armada of war canoes and the warriors transported on them were known as a “bola”, the Fijian term for a hundred canoes according to the traditional system of counting. A flotilla of 10 canoes was called uduudu.

Petty skirmishes employed smaller canoes but large-scale battles only involved the double-hulled drua, the equivalent to today’s high tech naval battleships.

Gigantic and plank-built, they easily exceeded thirty meters in length and were capable of transporting large contingents of warriors and crew. It is believed the largest drua carried in excess of 250 passengers on deck.

According to Fiji Museum records, the drua (called kalia in Tonga and alia in Samoa) was thought to be a combination of Polynesian and Micronesian building techniques and designs. It could travel at speeds of up to 25 knots in good weather conditions.

Fijian drua were distinctive in that they were made from vesi loa, a durable native hardwood that grew abundantly in limestone-rich islands of the Lau Group.

So to acquire large durable canoes, Tongans freely traded with the islanders of Lau and many islands there became “workshops” for the finest and most technologically advanced double-hulled vessels of the Pacific.

The ends of the hulls of these canoes were solid vesi wood to allow for more effective ramming during warfare.

“The well-built and excellently-designed canoes of the Fijians were for a long time superior to those of any other islanders in the Pacific,” Elsdon Best noted in the book, The Maori Canoe.

“Their neighbours, the Friendly Islanders, are more finished carpenters and bolder sailors, and used to build large canoes, but not equal to those of Fiji.”

Smaller drua were built too with a single hollowed log forming the base of each hull.

The largest drua were built using multiple planks expertly lashed together to form hulls over 40 metres long, with platforms eight metres wide.

During battles, the basic sea warfare technique was to ram this hardwood hulls into enemy canoes in order to sink or disable them, while the warriors in the latter boarded to engage in a bloody face-to-face merle.

Another tactic was to manoeuver the drua toward the outrigger hull of the enemy and cut through its rigging, dropping its heavy sail and engulfing all crew and warriors.

Sometimes a tactic known as “waqa ubi” was used. In this case, warriors hid in a canoe, which drifted ashore as if derelict. The warriors sprang out to attack their enemies when inspected

“The construction of the drua required a lot of time and resources,” the Fiji museum notes.

“Rich chiefs would typically employ a tribe of master boat builders to build them, with the construction of large boats taking over two years and being dependent on the supply of construction materials by the chief.”

During the US Exploring Expedition, Charles Wilkes observed that when chief Tanoa launched a canoe “ten or more men are slaughtered on the deck, in order that it may be washed with human blood.”

The drua were considered sacred so on their maiden voyage, they demanded blood. As an initiation rite while moving the drua from land to sea, human slaves were used as rollers, alternating with banana stems.

“Surrounded by ocean, the people of Fiji developed a wide range of canoes to meet their fishing, transportation, trade and warfare needs. In the 1800s Fijian canoes were faster and more seaworthy than the best ships Europe could produce,” the Fiji Museum adds.

Indigenous Fijians were skilful sailors who could navigate long distance cross the open ocean and had extensive trade networks with distant islands. The major maritime powers of Bau, Rewa and Lau all had large fleets of canoes with which to enforce and defend their influence.”

Wars aside, the use of Fijian canoes for travel, trade and centuries of survival in the largest ocean of the world

The drua remains one of the commonest sights today unfortunately only in the form of government, institutional and corporate emblems and logos. They no longer slice the waves of our Pacific seas like their used to in olden days.

Wooden, aluminium and fibre-glass boats now take up their place in coastal villages and the maritime islands. These are faster and physically ess demanding to build and drive across the high seas.

Their popularity has significantly meant the disappearance of Fiji’s traditional canoes.

Long before engines powered vessels across the Pacific, the drua — magnificent double-hulled sailing canoes — carried chiefs, warriors and traders across vast ocean distances.

They were symbols of innovation, prestige and mastery of the sea. Today, that rich sailing culture, which once spanned thousands of years, has nearly faded into memory.

The drua Ratu Finau stands as one of the last physical reminders of that proud maritime heritage.

Recognised as the oldest of Fiji’s great ocean-going double-hulled canoes, she now rests at the Fiji Museum.

Measuring 13.4 metres — small by traditional standards — Ratu Finau was built in 1913 in Fulaga, in the southern Lau group, at the command of Ratu Alifereti Finau, the eleventh Roko Sau of Lau and the fifth Tui Nayau.

He was the son of Ratu Tevita Uluilakeba II and Adi Asenaca Kakua Vuikaba, daughter of Ratu Seru Epenisa Cakobau, and a member of the noble Matailakeba household.

According to druaexperience.com, Ratu Finau was built for collector J.B. Turner and sailed to Suva for delivery.

Before eventually going into storage, she spent time sailing around Suva Harbour, competing in races against local yachts — and winning.

It is said that under ideal conditions, she could reach speeds of more than 17 knots, a remarkable feat that demonstrated the brilliance of traditional Fijian naval architecture.

In 1981, the Turner family generously gifted Ratu Finau to the Fiji Museum and the people of Fiji, ensuring her preservation for future generations.

Yet her story is more than history — it is also a lesson for the future.

In recent decades, human activity has caused severe environmental degradation and accelerated climate change, forcing governments and leaders worldwide to confront the damage inflicted on the planet.

For Pacific Island nations like Fiji, one of the most pressing challenges is addressing pollution and carbon emissions generated by the maritime transportation industry, particularly through the use of fossil fuels.

Ironically, the solution may lie in revisiting the very traditions that once defined us.

To reduce pollution and lower our carbon footprint, alternative power solutions must be explored — including the rediscovery of traditional sailing and boatbuilding knowledge. The craftsmanship and skills required to build and maintain drua were not only sustainable but entirely reliant on renewable energy: the wind, the sea and human ingenuity.

As the world searches for cleaner and more sustainable transport options, Fiji’s ancient seafaring legacy offers both inspiration and practical wisdom. The silent hull of Ratu Finau reminds us that before engines and emissions, we already knew how to cross oceans — guided only by the wind.

This is a re-run of an article published previously in The Sunday Times on January 31, 2021

History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor.

A drawing of an indigenous Fijian sailing canoe. Picture:EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG

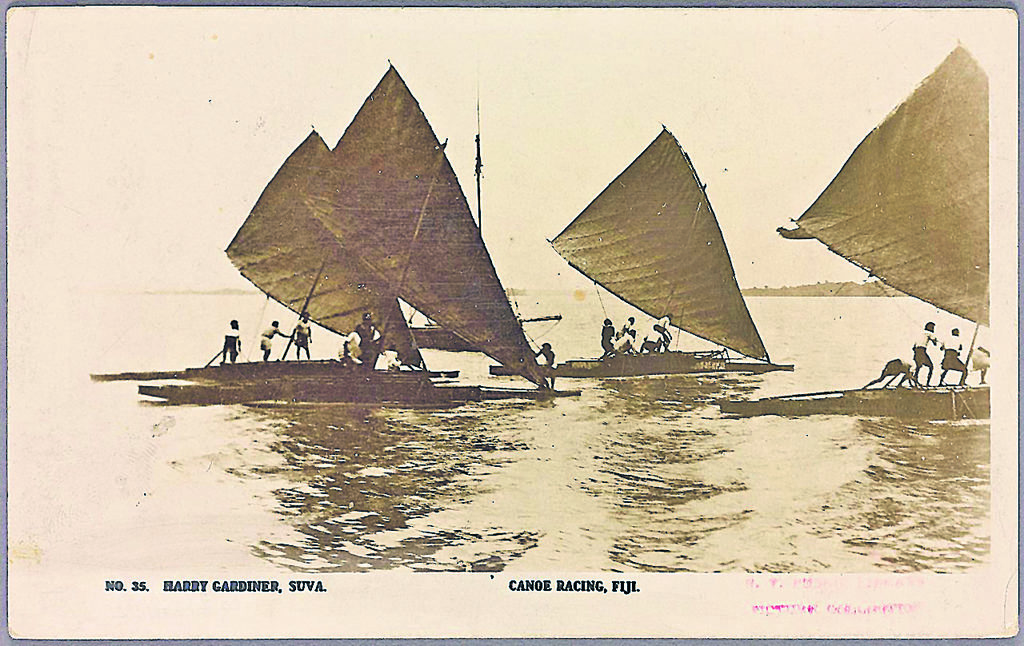

Right: Canoe race in Fiji.

Picture: EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG

Villagers push and pull the hollowed hull of a drua and drag it to the village. Picture: FILE

A sketch of a Fijian canoe and a sailing ship. Picture: WWW.RMG.CO.UK

The canoe, Ratu Finau, on display at the Fiji Museum. Picture: FIJI MUSEUM

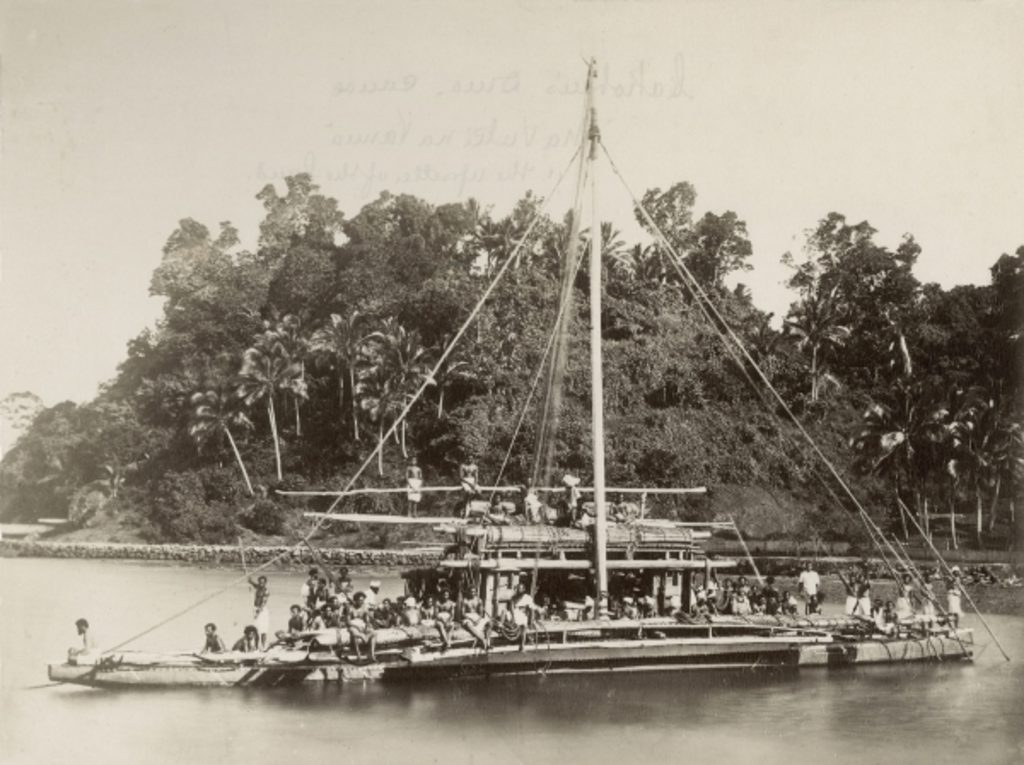

A doubled-hulled canoe with passengers on board. Picture:FORUMS.SAILING ARNACHY.COM