Fiji has a rich array of traditional wooden artisanal products.

While menacing crafts such as clubs and the mighty sea-voyaging war canoes (drua), have enjoyed fame, the lali (wooden gong or drum), though an important part of life in old Fiji, seemed to have faded in prestige.

In ancient times, the lali belonged to the community as a communications tool. It summoned the early Fijians to important gatherings and warned them during an imminent attack.

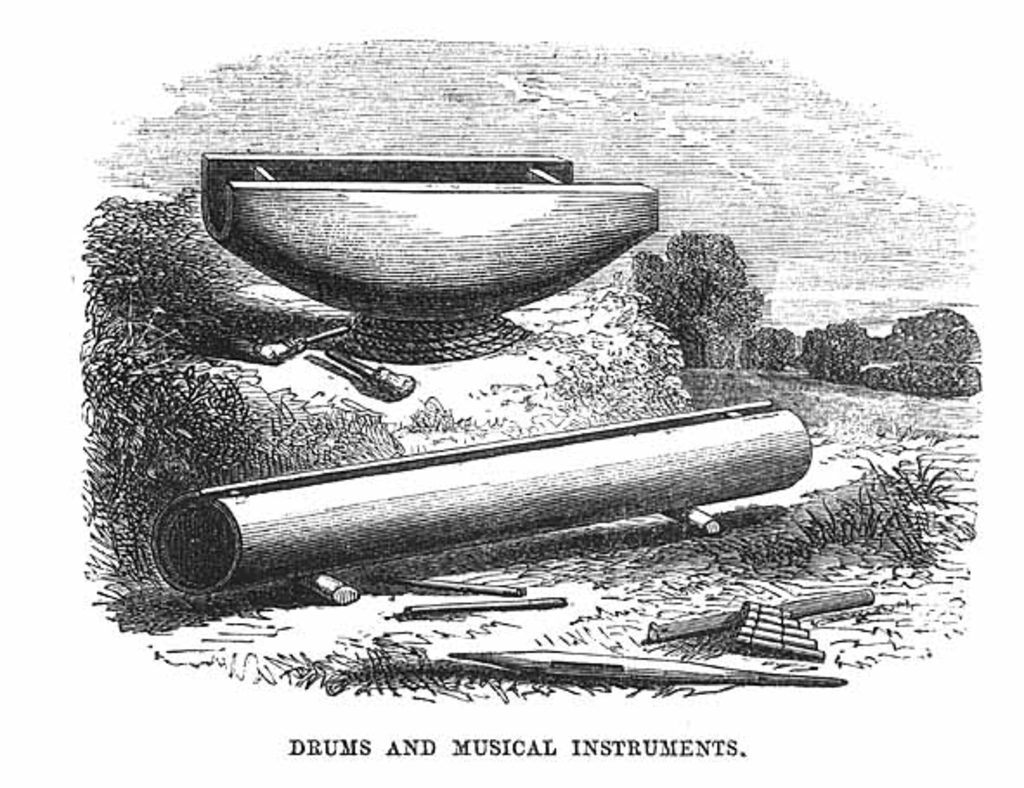

The small hand-held lali were used as musical instruments during traditional dances known as meke while the huge ones measured up to several feet, depending on the seniority of the village chief who owned them.

According to Rod Ewins in the Domodomo article titled “Drums of Fiji”, the lali was more common in pre-contact times and was the speciality or iyau of “specific localities”.

Ewins said the islands of Southern Lau, in particular, were famous for the variety of male and female wooden artefacts they fashioned.

These islands had an abundant supply of the coastal hardwood tree called vesi, which was used largely in the manufacture of wood crafts like war canoes, kava bowls called tanoa and the lali.

Lali were commonly made from dilo, tavola and vesi timbers because they were dense, and acoustically resonant.

Vesi thrived in limestone-rich islands, where the tree could grow very tall and wide around the trunk.

Stone adzes, called matauvatu or isivi, which were strenuous to make and required regular sharpening, were the primary tools employed in the felling and shaping of vesi trees using thick straight trunks.

Ewins said the cutting of a new lali, because it was communally owned and important, was always a great event.

When a completed one was transported on a canoe to its intended destination, the lali was beaten all throughout the journey making. The lali’s specific beat told coastal villagers that it had just been completed and was being transported by sea to its owners.

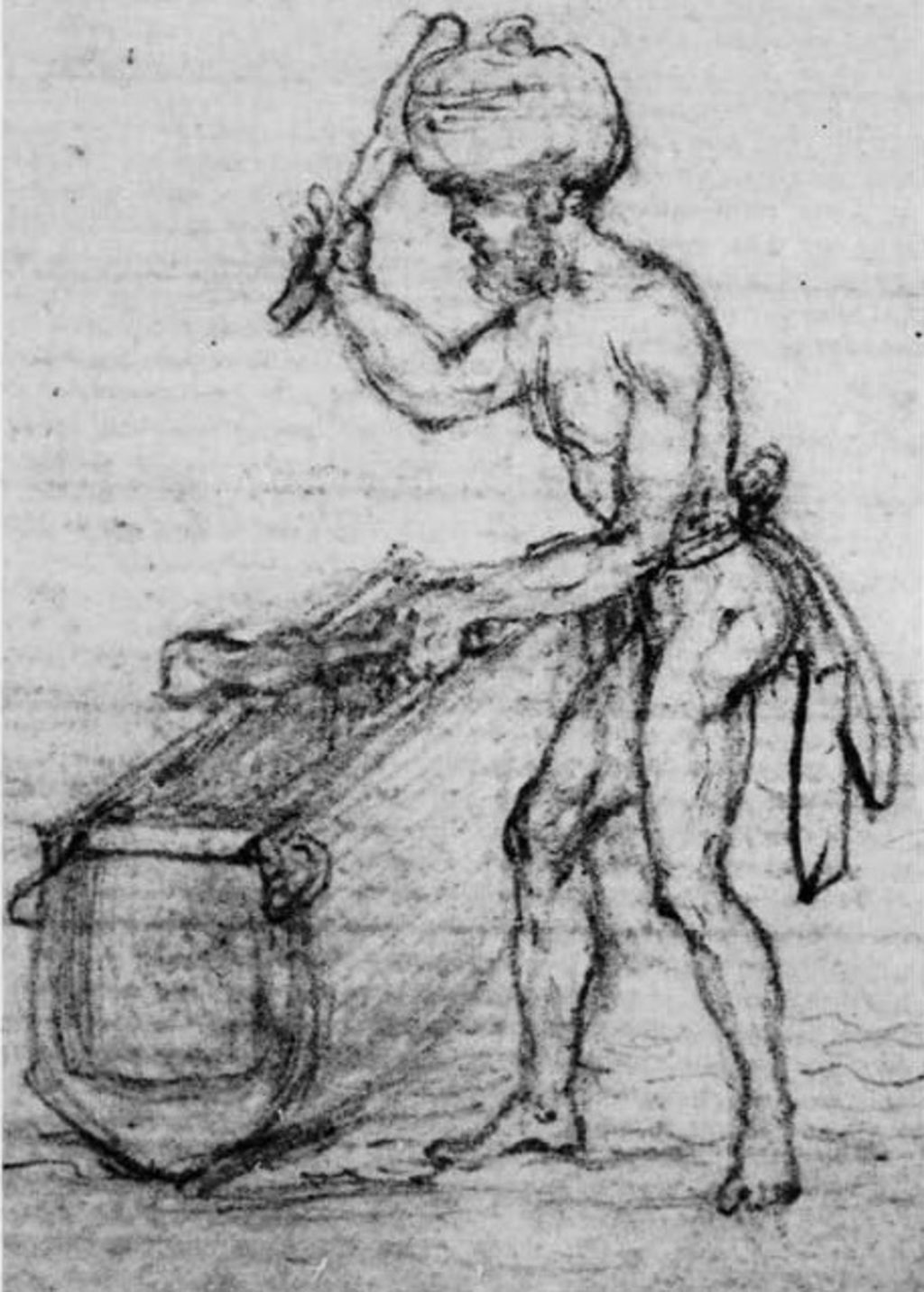

The making of a lali was a physically intensive job, requiring a lot of upper body strength. Once the preferred length of the lali was cut from the felled trunk, it was slowly given form and shape.

The rough shaping of the log was done in the forest using the felling axe called valevatu.

Ewins said firstly, the side of the log that would form the top the lali (ketena) was chopped along its length with the axe, and then adzed flat with the valevatu through a process called cici kete.

The outsides were then shaped through a shaping action called umani before the hollow interior (loma ni Lali) was strongly chopped out (tuki drake).

When the basic form of the lali had been decided and the weight of the log reduced, by the emptying of the sides and the interior, it was then carried back to the woodsman’s home using two poles called ivua to be completed by fine chiselling and detailed handiwork.

Sometimes taking the rough body of the lali to the village took a few miles of walking on foot.

Finishing of the cavity was done using the tools, tabu magimagi and the calocalo. The sides and underneath of the “belly’ (dago ni lali) was adzed to a good shape and reasonable finish.

It was common practice to carefully place the finished lali inside the bachelor’s quarters known as valenisa or burenisa. It was only brought out for beating during special occasions or to signal special events.

Ewins said while in modern times the lali was merely used to tell the time in schools and in churches, it had many more uses in the past.

He said the lali and its beats differed according to their significance, and were meaningless to strangers but were easily recognised by those who heard them and understood their message.

“Even in living memory, lali could not be beaten casually….”

In history literature, reference was made to the bamboo instrument called derua than to the lali.

The beating of the derua tubes signalled that the corpses of bokola killed in battle were being carried into the village ready for feasting.

Describing the beating that accompanied the bokola’s arrival, Reverend Thomas Williams wrote in Fiji and the Fijians: “When the bodies of enemies are procured for the oven, the event is published by a peculiar beating of the drum…”

Some of the lali beats that were used in the olden days included the vakataratara, lali in tabua, lali ni waqa, lali ni kabakoro, lali ni bokola, lali ni bure kalou and lali ni sautu,.

The vakataratara was for raising the tabu, four nights after a chief’s death while the lali ni tabua (beaten on two drums, the first called kaba bu) was sounded when receiving a tabua or in times of stress or war.

The lali ni kabakoro was beaten when besieging a village while in very formal warfare (ivalu votu) a big wooden lali was beaten to warn the defenders when they were likely to be attacked. The number of beats at the end showed the number of days before the planned attack.

During a siege, the lali was beaten non-stop to signal for help from “friends’ and allies.

The lali ni bokola was beaten from behind the ramparts of a fortified village, within the field or on board a canoe.

“It was beaten to proclaim the capture of enemy bodies and the start of the victory dance over them prior to their sacrifice and cooking,” Ewins said.

The victory dances were, the cibi for men and the dele or wate for women, the latter performed with a sexual theme and vigour.

Due to the fact that the lali had a significant communications role to play during battle, it was prized as “spoils of war”.

In the book The Hill Tribes of Fiji, colonial administrator Adolph Brewster wrote that during one of Cakobau’s victories in the 1870s the Bauan chief’s spoils of war included “the great big wooden lali or war drums… “.

The sacred lali ni burekalou was beaten at the village temple, lali ni sautu was sounded to signify a truce reached in battle and lali ni vutu was beaten at the birth of a chief.

The lali ni meke or dance drums were the most popular pastime of Fiji and signified peace times. It provided music for the chant that were sung and was accompanied by sticks and derua.

Lali ni meke are similar in shape to the large drums, only they are typically smaller (30 to 60 centimetres long). They are used during entertainment segments for chief or adored during special celebrations or for traditional gatherings.

“The sound they emit when struck with their little beaters is sharp and piercing but not resonant,” Ewins noted.

Today, the huge war drums are no more, its prominence usurped by the slightly smaller ones beaten in villages to summon people to church or for telling the time in rural schools where there are no bells or sirens.

Some experts say the lali is neither a drum (because it has an open hollow), nor a gong because it is does not have flat plates.

Whatever it is technically, it showcases the superb craftsmanship of old traditional woodsmen, who created objects still capable of “making noises” in 21st century Fiji.

(This article was compiled using information from the article Drums of Fiji by Rod Ewins published in the Fiji Museum quarterly magazine, Domodomo Volume 4 in 1986)

The tail side of a Fijian five centt coin depicting a lali. The Picture:www.collectorbazar.com

A drawing of a lalli. Picture:WWW.JUSTPACIFIC.COM

Right: Wooden slit drum beating.

Picture:WWW.JUSTPACIFIC.COM