IN olden days, traditional burial sites like caves were kept a secret during tribal wars.

In Fiji, burial caves were linked to ancestral identity and kept a secret to preserve spiritual balance, cultural heritage and protect remains from desecration from enemies.

Cave burials were a common burial custom, as described by Wesleyan missionaries who served here in the 1800s.

Profound secret

One of those Wesleyan missionary and anthropologist was Reverend Lorimer Fison who arrived in Fiji in 1863.

He was an adviser to natives when he arrived and recorded most of his expeditions and experiences in Fiji.

His notes on Fijian burial customs have been used in research papers and has enlightened many on the burial rituals once practiced in the past.

Reverend Fison wrote, for many tribes in Fiji burial places for their chiefs were kept a secret.

This was to avoid enemies from taking revenge upon a late chief by digging up his remains, insulting or even eating his body after he had departed.

Reverend Fison said in some places the dead chief was buried in his own house, and armed warriors of his mother’s kin kept watch night and day over his body.

After a time, his bones were then taken up and carried by night to a far-away inaccessible cave in the mountains, whose position was known only to a few trustworthy men.

Fison wrote that ladders were constructed to enable people to reach the cave and later taken down when the bones had been deposited.

He recorded many frightful stories told in connection with the custom of burial. It was certain that not even decomposition could escape the revenge of cannibals if they could locate a grave.

Fison said in one instance when a hiding place was discovered, the bones were taken away, scraped and stewed down into a horrible hell-broth.

Cave burial according to the Reverend was common in Fiji.

It was found in many parts of the group, thought it was not generally practised.

He wrote that people of one village might be cave-buriers while their neighbours on either side of the island buried their dead in graves.

The dead and sometimes the dying according to Reverend Fison were laid in caves without any covering other than the cloth or mats in which they were wrapped.

At Nakasaleka (Kadavu) there was a deep rocky chasm into which the dead are thrown headlong, Fison wrote that only commoners were disposed of in that manner while chiefs were treated with greater ceremony.

In all probability the practice of cave burial was far more common in the older times.

Na i Vakasara Cave

With that historical account of burial caves, the mataqali Namara of Namosi also share of their sacred burial cave situated at Navunimolau in Navunibau Village.

The burial site according to the mataqali is 900 metres away from the new Dakuinaroba Bamboo Park and the main road.

Even though the cave is just a few metres away from the village, not a lot of people have visited the site as it is considered a sacred area.

The cave was once considered a traditional refuge were the mataqali’s forefathers were taken when the battle cry was sounded during tribal wars or conflict. It was also a place where village elders were taken to await death.

The sacred place is known as Na i Vakasara.

According to mataqali accounts, food would be secretly taken to those that were in the cave and at times the elderly remained there until their passing – making it their final resting place.

Today, the burial site remains a sacred area, honoured with deep respect for those who have passed.

Mataqali Namara Trust vice chairman, Paulo Rauto said the name of the cave, the Na i Vakasara meant to “curumaka” or in English to put in or ingress.

Rauto said it was common for elders to be taken up to the cave to await their passing to avoid being killed and eaten by enemies.

To ensure a peaceful death for their elders, it was villagers’ responsibility to move their elders to the cave as cannibalism was a ritualistic act of warfare and a dreaded tradition at the time.

A historical site

Not a lot of villagers have had the chance to visit the cave but the mataqali hopes that by including it in the park tours it could allow its people and visitors to learn of its historical significance.

Mr Rauto said they also hoped that more about their ancient history and traditions could be shared when more of their historical sites were included in the park’s excursions.

“This will be one of our projects and we hope it will enlighten a lot of people about our deep rooted history,” he said.

History being the subject it is, a group’s version of events may not be the same as that held by another group. When publishing one account, it is not our intention to cause division or to disrespect other oral traditions. Those with a different version can contact us so we can publish your account of history too — Editor.

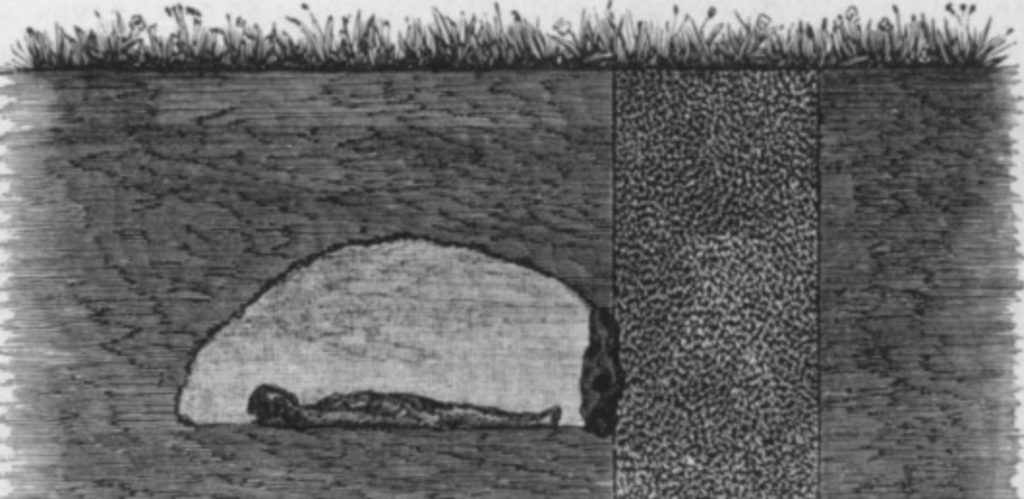

An illustration of a burial on alluvial soil cave in Fiji.

Picture: US.ARCHIVE.ORG

The Na i Vakasara is situated close to the rock mountain shown opposite the Dakuinaroba Bamboo Park. Picture: ANA MADIGIBULI

Mataqali Namara Trust’s vice chairman, Paulo Rauto. Picture: KATA KOLI

Members of mataqali Namara with stakeholders at Navunibau Village in Namosi. Picture: TOMASI VAKADRANU

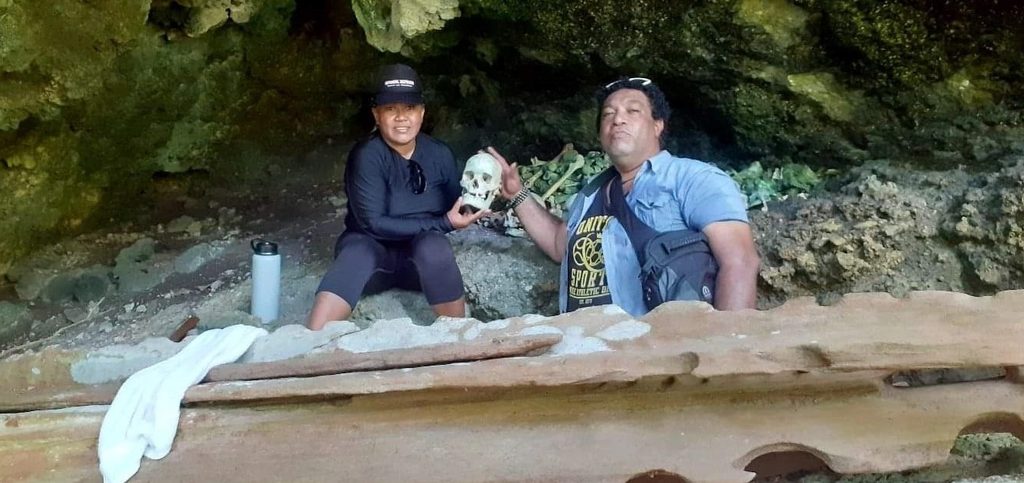

The Sunday Times writer, John Kamea in a skeleton cave (Yacata Island) in the form of a limestone grotto. Burial caves are common in many parts of Fiji. Picture: FILE

A cave of bones in Fulaga, Lau.

Picture: WWW.SVSUGARSHACK.COM

Right: Several skeletal remains were discovered in early 2025 inside this cave in Nalidi, Ra. Picture: FILE