THIS week the Methodist Church in Fiji and Rotuma had its annual conference and celebrated its 190 years anniversary.

While we acknowledge the tremendous efforts of early missionaries in the establishment of missions in Fiji, we should also applaud locals who helped pave the way for the gospel.

Stories of Reverend William Cross and Reverend David Cargill arriving in Fiji is well-documented, particularly how they had introduced methodism to Fijians. Pioneering missionaries that changed the course for Fiji, Cross and Cargill with many other Wesleyan missionaries that followed converted Fijians – those that were once known as savage man-eaters.

The conditions of Fiji and of Fijians today compared to 1835 is one of the world’s outstanding examples of the benefits of Christianity. As Fijian slowly accepted Christianity, they quickly thrived in society.

According to the Pacific Islands Monthly article on October 24, 1935, Fijians were among the most attractive of the South Seas races and were intelligent. They had easily acquired the arts and crafts of European and had praiseworthy social qualities. They were also hospitable and law-biding, have a fine spirit and national pride – they were Christians.

As time went on and although European missionaries tended to give Fijian interest precedence in the mission, Fijians had slightly resisted European dominance as written by Kirstie Close-Barry in the “A Mission Divided”.

With that in mind, a few particularly the farmers from Toko near Tavua articulated their desire for a national Fijians church.

The farmers consisted of many iTaukei from around the country, particularly from Ra who planted sugarcane crops.

During the Fijian session of the 104th Annual Methodist Fiji District Synod that opened on October 13, 1941, the Toko farmers approached the mission’s chairman, William Green with the superintendent of the Suva Indo-Fijian circuit Maurice Wilmshurst and the principal of Davuilevu, Reverend Robert Green.

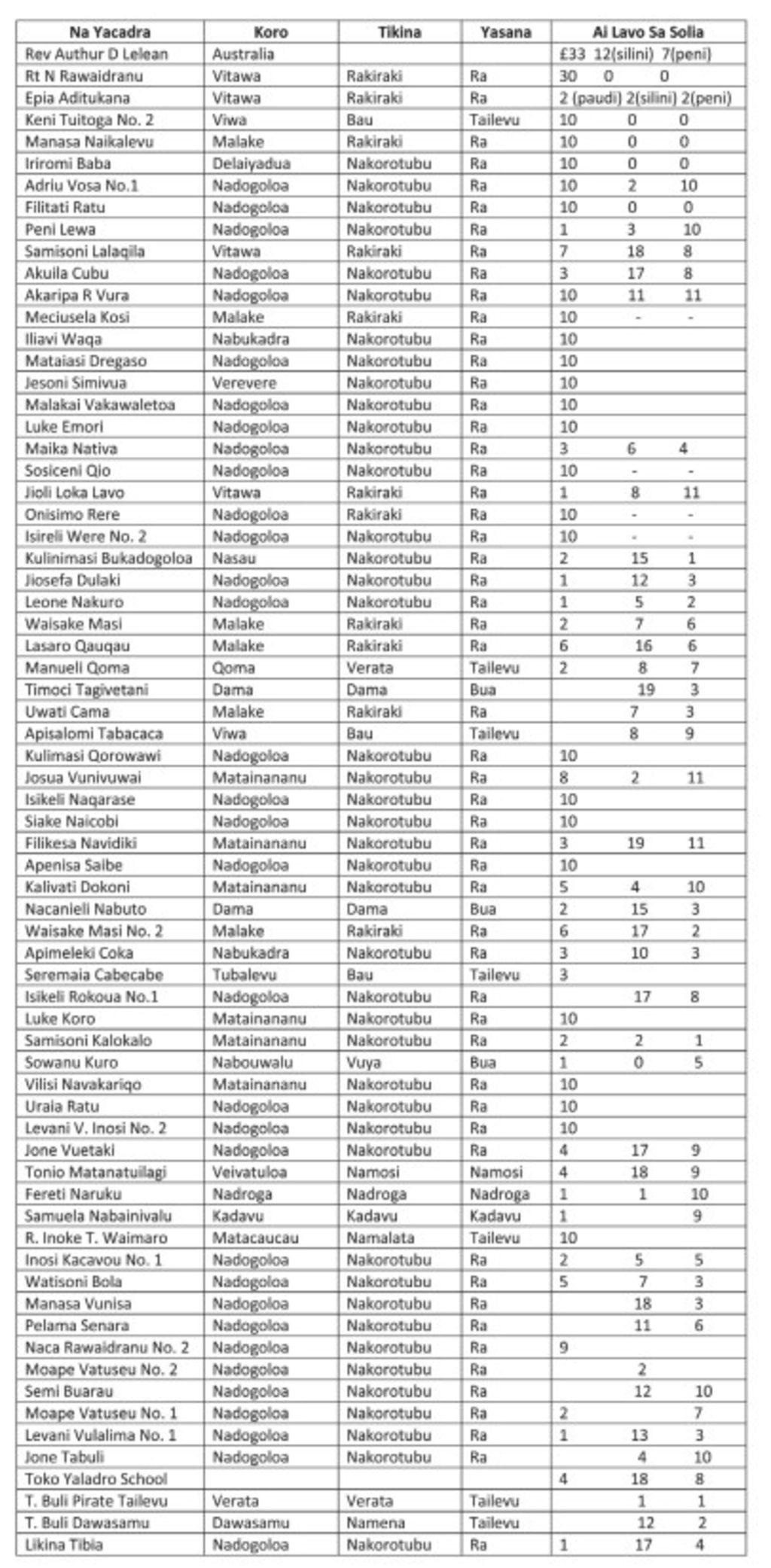

The farmers presented tabua to the chairman that were collected from chiefs throughout the islands and 500 pounds from its members who worked in sugarcane fields. The total contribution was 118 tabua and 500 pounds.

Like any important request, the presentation involved a lengthy speech done in customary fashion. There the farmers asked William Green, the mission’s chairman to fulfil the promise of self-government and self-support.

While overseeing the proceedings, William witnessed the changing tide as the sands swiftly shifted under the feet of the European ministry.

The tabua, according to Barry carried the farmers’ hopes for the future, by transferring it to the hands of William Green, they hoped that he would consider their request and enact their plan for self-governance.

The farmers wrote a letter, entitled “The new way in which advance may be sought”, that outlined their aims and wants.

The farmers according to Barry simply wanted to be partners in establishing the Fijian Methodist church. The plan of course relied on chiefly networks to levy support in the broader Fijian community.

The farmers had intended to go to the Council of Chiefs and explain the scheme to gain support, believing that the chiefs would “not be able to neglect it for the church and land is theirs.

The rhetoric of exclusion, tradition, chief, lotu and vanua were adopted to describe the aims of the farmers – this was a Fijian movement for a Fijian church, Barry wrote.

The synod accepted the money and placed it in a trust.

Many Fijians contributed financially, most of whom were from Nakorotubu in Ra.

Tuirara Levu (church steward) of Bureiwai Circuit, Meli Rareba 64, at his home in Matainananu in Bureiwai briefly shares how the elders from his village had helped in paving the way for Fijian autonomy within the church.

He said growing up they were told of how man from Navatu in Ra led by Ratu Nacanieli Rawaidranu had contributed immensely to the Fijian Lotu Wesele.

But during his trip to attend a Methodist Church’s annual conference in 2006, Mr Rareba had an opportunity to view the list of elders who had gone to work as farmers and helped raise the 500 pounds given to the Methodist mission chairman then, William Green.

“I was shocked when I saw the list of names. It had one of our village elders and the amount he had contributed.

“When the idea was being put out for people to go work and try to earn for the purpose of independence within the church – the men of Bure also volunteered.

“Those from Bure that contributed was Luke Koro and Samisoni Kalokalo, those were the names I saw on the list,” he said.

But apart from the two gentlemen, there were also others from Bure that had joined the cause. They were Vilisi Navakariqo, Josua Vunivuwai and Filikesa Navidiki.

These were the amounts they contributed – Luke Koro gave 10 pounds, Josua Vunivuwai gave eight pounds/two shillings/ 11 pence, Filikesa Navidikigave three pounds/19 shillings/11 pence, Samisoni Kalokalo gave two pounds/ two shillings/ one pence, while Vilisi Navakariqo gave 10 pounds.

“To see our elders contribute to something important like that gives us great joy and pride,” he said.

“They faced a lot of challenges in the past, but they still did it because they knew it was for the greater good of the people.”

“Bureiwai might have a small circuit, but it has contributed in a big way to the growth of the church and we’re grateful for the tremendous work they’ve done.”

Those farmers helped laid the foundation to what the Methodist church is today in Fiji.

Local ministers in Nabouwalu. Picture: THE MISSION DIVIDED

Inside a local minister’s house. Picture: THE MISSION DIVIDED

Meli Rareba of Matainananu Village with his family in front of their home in Nakorotubu, Ra. Picture: ALIFERETI SAKIASI

The church in Bureiwai between Matainananu Village and Delaiyadua Village. Picture: ALIFERETI SAKIASI

Some of the names of the farmers that contributed the 500 pounds. Picture: SUPPLIED