After four years immersed in mission life across Vanua Levu, Columban priest Fr Frank Hoare entered 1978 with more cultural encounters, community bonds, and a much-needed return home. We left off with Fr Hoare spending Christmas in Vanua Levu, at the end of 1977, helping a woman in labour get to hospital in time to deliver her baby on Christmas Day. Now, we rejoin him as he navigates new responsibilities in the bush settlement of Vudibasoga, shares a touching midnight moment with a nervous groom, and finally returns to Ireland, only to find that missionary time moves quite differently from the clock-bound pace back home.

Lantern light

With Fr Ed Quinn away on holiday, the responsibility of managing the new parish centre at Vudibasoga fell to Fr Hoare and Fr Theo. It is Tuesday, February 28, 1978, and the mission area had no electricity, and priests rotated between the coastal station at Nabala and the bush setting of Vudibasoga, a place alive with both construction work and spiritual labour. At night, they celebrated mass in a shed, lit by a single benzene lamp that hissed as it burned. “I try to raise my voice to be heard over it,” Fr Hoare wrote. “The faithful elders, however, struggled to catch the soft-spoken sermons of Fr Theo.” When Fr Hoare relayed this to his fellow priest, Fr Theo’s response was filled with humorous self-awareness: “When I start a sentence in Fijian I often get to the middle and don’t know how to end it. So, I drop my voice and let the people guess how it ends!” Their efforts to improve their Fijian and their ministry continued amid rural challenges.

The Groom at the fire

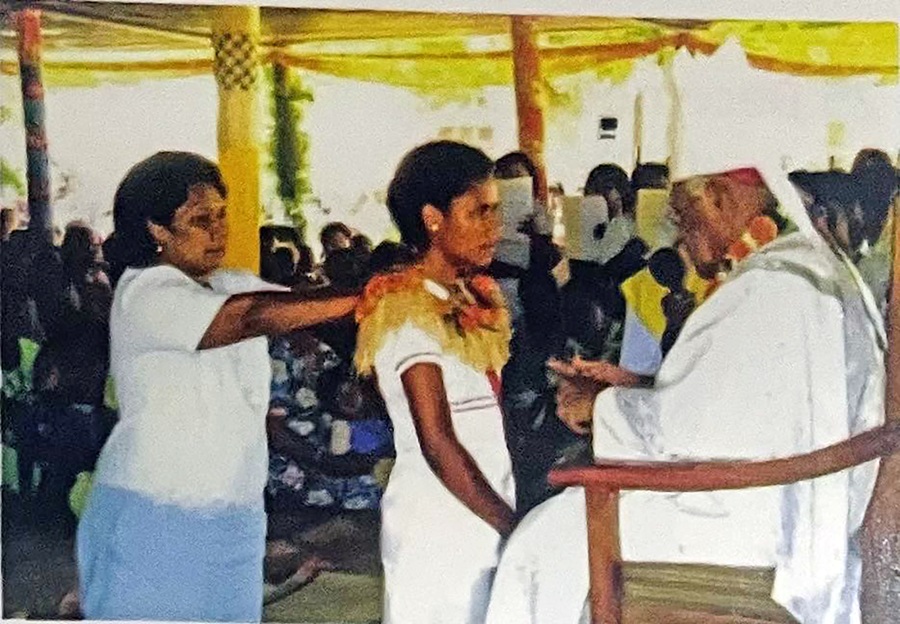

Almost a month later in a remote village, the local catechist approached Fr Hoare with news: a couple, Iowane and Maria Rosa, together for 18 years and parents to five children, were ready to be married in the church. With the catechist’s assurance that they had received instruction, preparations were swiftly made. Fr Hoare met the couple the evening before the wedding, reviewed the ceremony, and encouraged them to say their vows directly to each other, giving them a copy to memorise. That night, at 2am nature called and led the priest to an unexpected sight. In the centre of the village, by the glow of a flickering fire, stood the groom. He was quietly rehearsing his vows. “My heart went out to him.” Moved by the moment, he told the groom to rest and not worry. He would prompt him during the ceremony. The next day, with quiet nervousness and steady resolve, Iowane vowed his love until death. The wedding went off without a hitch and perhaps with even more meaning than any meticulously rehearsed ceremony.

Back to brown bread and rashers

After more than four years in Fiji, Fr Hoare returned to Ireland in May and to the warmth of home. His mother greeted him with a hand-knitted sweater, “now that my blood has been thinned in the South Pacific,” he quipped. Homemade brown bread, rashers, and family stories filled the days. Preaching at Sunday Mass for over 1000 people, Fr Hoare shared tales of Fijian hospitality, the bula greeting, and the tradition of calling strangers to join a meal. “This morning, I said Sunday Mass for more than 1000 people in our parish church. “In my homily, I spoke about the fascinating cultures of Fiji, how passing strangers greet you with ‘bula’ (good health) and a smile and how a family eating dinner calls a passer-by to come and join them. “Some lay ministers helped to distribute Holy Communion. I felt happy giving the final blessing 10 minutes before the hour.” He also shared the relaxed rhythm of Fijian masses, which rarely ended on the hour. This cultural contrast came into sharp relief when an agitated newspaper seller confronted him outside church. “All the other priests finish mass in 30 minutes!” the man fumed. “Now I’ll miss the crowd at the next church!” Stunned, Fr Hoare recounted the incident to his mother. Her immediate response: “Wait until I catch up with that fellow. I’ll give him a piece of my mind!”

A tabua on Inish Meáin

By July, Fr Hoare was also invited to support The Far East magazine by preaching in Irish across the Aran Islands drawing on his own schooling in the language. On Inish Meáin, he spoke passionately about Fijian generosity, rituals, and respect for elders. After mass, a local man approached him and offered a surprising gift, a real tabua, a whale’s tooth. “I was delighted to accept. I was also curious to know how he came to own one,” Fr Hoare said. The story the man shared was a strange yet poetic one. “A few years ago, a whale was beached here on the island and died,” the man said. The County Council tried to get rid of it as the stench was becoming unbearable. “It was too big to bury but they thought that they could burn it because of the oil inside. “However, that failed. “So, we islanders agreed that for $1000 we would get rid of it ourselves.” Armed with saws and spades, they dismembered and buried the whale, scattering pieces in the sea. Some took souvenirs. “One of the whale’s vertebrae is now a stool in the pub. “And I took this tooth.” He even shared a poem he had written in Irish, closing with an image of the whale’s heart, drifting back out to sea.

A journey between worlds

This part of Fr Hoare’s story reveals the bridge he walked between two very different worlds the lush, communal life of Fiji and the structured pace of home in Ireland. Yet in both places, he found deep meaning, unexpected encounters, and a thread of kindness that tied it all together. His mission continued, not just in preaching, but in listening, laughing, learning, and always being present.

- More stories await