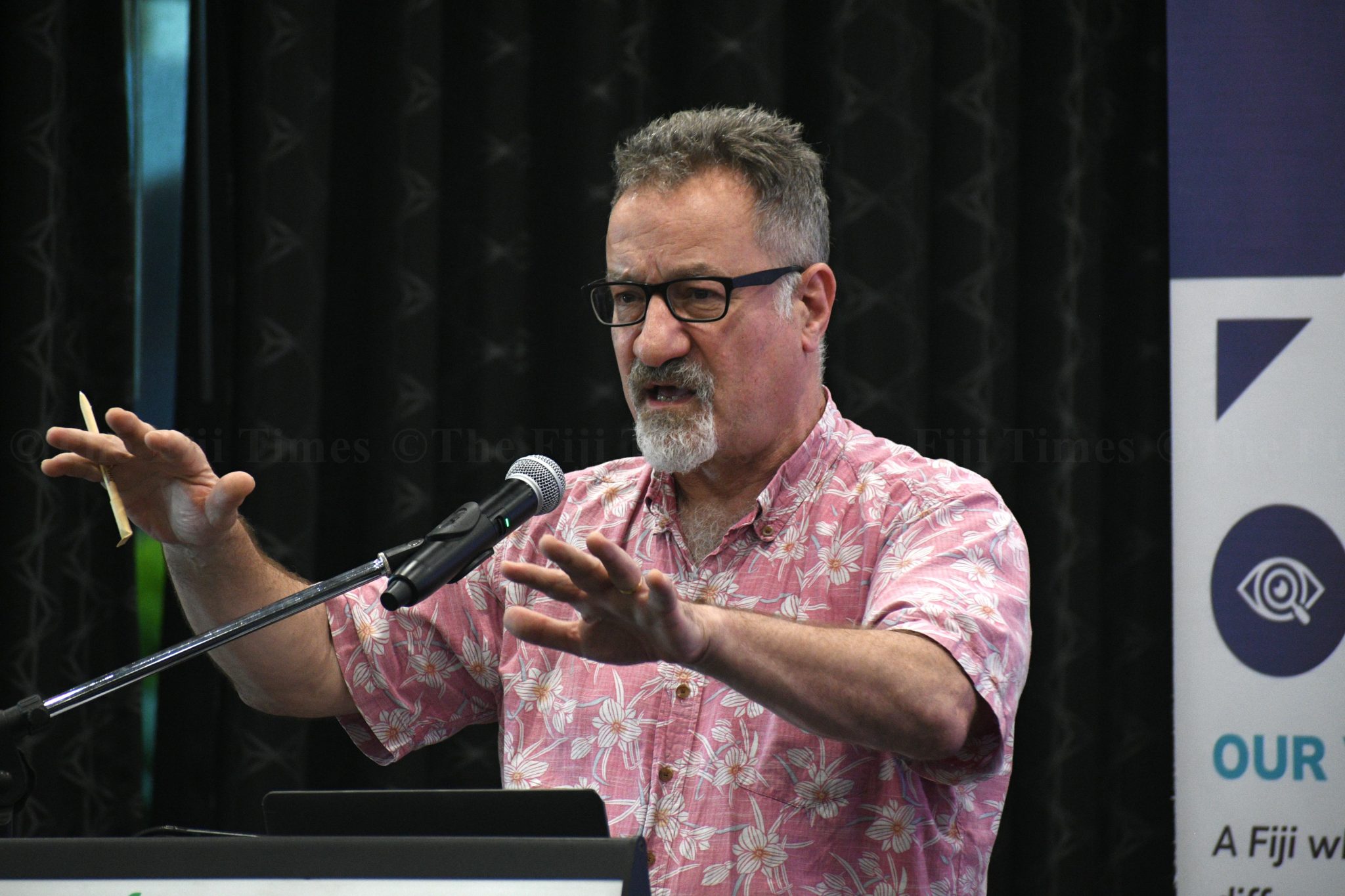

Political scientist Jon Fraenkel says Fiji’s courts have repeatedly faced an impossible dilemma when asked to rule on constitutions and governments born out of coups — torn between legal principle and political reality.

Writing on the 2000 and 2006 coups and their aftermath, Fraenkel argues that courts everywhere struggle when confronted with unconstitutional takeovers.

“Law courts are nowhere particularly good at dealing with coups or imposed authoritarian constitutions,” he notes, “not least because the first question they invariably ask is about the source of their own jurisdiction.”

Fraenkel says judges are often hesitant to declare such issues beyond their reach.

“Some legal scholars argue that courts should declare themselves unable to address such ‘meta-legal’ political questions,” he writes, “but that is a conclusion many judges are understandably reluctant to reach.”

In 2025, Fiji’s Supreme Court was asked to consider the status of the 2013 Constitution, introduced by decree after the 2006 coup and replacing the abrogated 1997 charter. The constitution’s amendment rules — requiring 75 per cent of registered voters in a referendum — made change almost impossible.

The Court faced a constitutional paradox.

“The judges were thus caught between Scylla and Charybdis,” Fraenkel explains — to either uphold a constitution imposed without popular consent, or reject its legality and undermine the very basis of their own authority.

To resolve the impasse, the judges selectively recognised the constitution, but not its rigid amendment provisions, drawing instead on common law and the right to self-determination.

Fraenkel says this approach, similar to the landmark Chandrika Prasad ruling of 2001, opened space for democratic debate.

“In this case, like the earlier Chandrika Prasad case, the Fiji courts delivered an appropriate and reasonable judgment opening a path for democratic deliberation.”

The Chandrika Prasad case had declared the post-coup interim government unlawful — relying on the so-called “efficacy test” to assess whether a regime truly commanded public support.

But political turbulence soon revealed there was no realistic alternative government-in-waiting.

Fraenkel notes that even the ousted prime minister Mahendra Chaudhry advised dissolving parliament, amid internal party rifts and fears of renewed instability.

“After the tumultuous events of May–July 2000, it was inconceivable that Chaudhry could return as Prime Minister,” he writes.

Ultimately, elections were called — a decision Fraenkel describes as the best available option at the time, despite deep social and communal divides.

Fraenkel concludes that distinguishing genuine public support from fearful submission is extraordinarily difficult — for courts, civil society and political analysts alike.

Still, he says Fiji’s judiciary has at times managed to steer a path that preserves space for democracy.

“The August 2025 Supreme Court judgment,” he observes, “again relied on a rule of recognition — echoing Chandrika Prasad — to navigate between legality and political reality.”