On October 10, 1874, the course of Fijian history was irrevocably altered when 13 of Fiji’s highest-ranking chiefs signed the Deed of Cession, handing sovereignty of the islands to Great Britain.

Though this act marked the beginning of Fiji’s colonial chapter, it also birthed an institution that would become a cornerstone of Fijian identity and governance — the Great Council of Chiefs.

Rooted in Clause 7 of the Deed of Cession, the council emerged not only as a recognition of chiefly authority within the colonial framework, but also as an advisory body intended to bridge traditional Fijian governance with the imposed British system.

The clause ensured that the rights and interests of Tui Viti and other high chiefs would be acknowledged so far as it is consistent with British sovereignty, a critical acknowledgement that safeguarded chiefly influence amid sweeping change.

In 1875, the British Charter that formalised the Colony of Fiji was adopted in Draiba, Ovalau. That same year, the role of the Roko Tui — provincial administrators drawn from chiefly ranks — was created.

Appointed by Fiji’s first governor, Sir Arthur Hamilton Gordon, these Roko helped govern native affairs and ensured colonial policies were tailored to the needs of the Fijian people.

A year later, the Council of Chiefs held a historic meeting in Waikava, Vanua Levu, where the 1876 Native Affairs Ordinance was introduced.

This ordinance laid out a governance framework specific to the indigenous Fijian population and included a census — one of the first efforts to formally record demographic data across the islands.

During this era, the council was gradually immersed in Fiji’s commercial and agricultural evolution. In 1878, they authorised the soli ni yasana (provincial levy), a tax system that still influences provincial finances today.

Notably, at an 1878 meeting in Bua, the chiefs recognised the economic potential of sugarcane and supported the establishment of sugar mills to ease taxation and boost local prosperity.

Despite colonial limitations, the Council enjoyed a collaborative relationship with the Crown. Chiefs readily acknowledged Queen Victoria as their sovereign, and through Sir Arthur Gordon’s strategic use of traditional structures, Fiji’s provincial governance system solidified.

However, Gordon’s policies — particularly the restriction on Fijians working on plantations — triggered a new demographic reality: the arrival of indentured Indian labourers in 1879. The council responded proactively by supporting the establishment of Vuli ni Tu (leadership schools) for Fijian youth, aiming to prepare them for future leadership and safeguard their cultural identity.

In the following decades, the council became more engaged in national issues. In 1890, they petitioned the government to investigate land claims made by settlers, reflecting growing unease over indigenous land security.

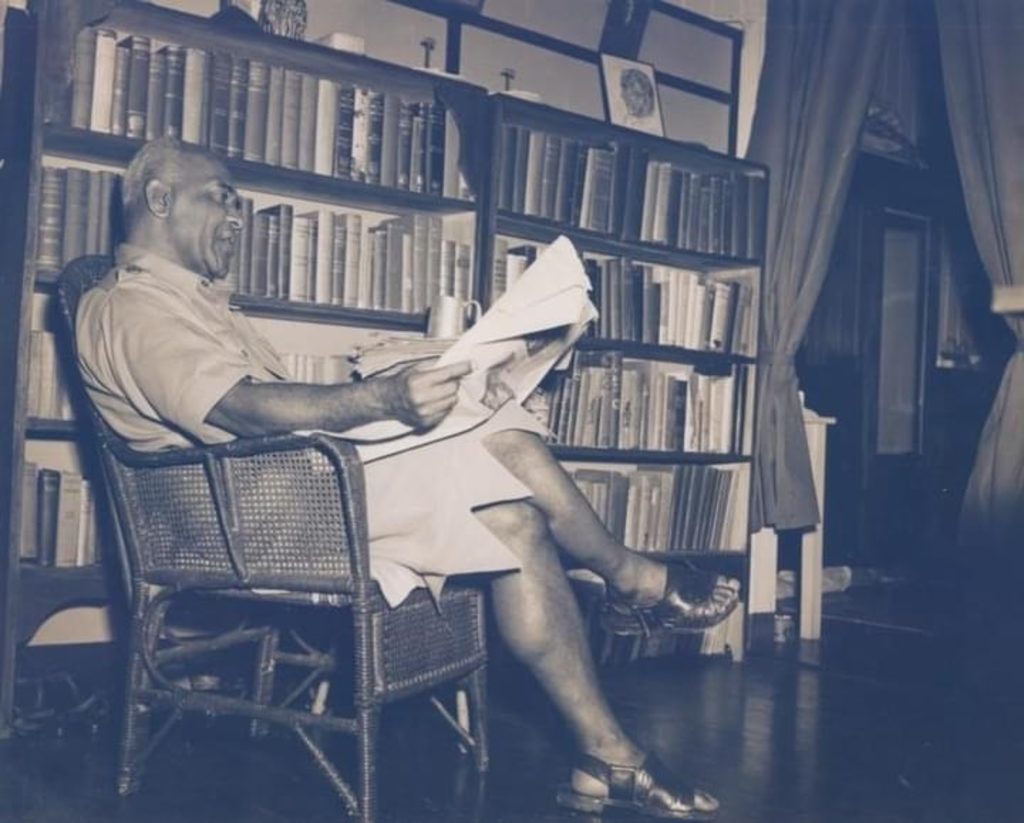

This concern culminated in the Native Lands Trust Ordinance of 1940, championed by one of Fiji’s most influential leaders, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna.

A scholar, soldier, and statesman, Ratu Sukuna’s role in creating the Native Land Trust Board ensured indigenous land rights were protected in perpetuity.

He oversaw the registration of over 80 per cent of native land — a monumental achievement for any colonised society. His leadership exemplified the council’s transition from a ceremonial advisory body to a proactive force in national development.

By the mid-20th century, the council had also focused on education and health, helping establish Queen Victoria School, Adi Cakobau School, and Twomey Hospital for leprosy patients. As political consciousness among Fijians grew, the council played a pivotal role in guiding the country towards independence in 1970.

With the adoption of the 1970 Constitution, the council gained real political clout—nominating senators and selecting the president and vice-president under the 1997 Constitution.

Yet, Fiji’s post-independence journey was not without turmoil. Coups in 1987 and 2000 forced the council to assume a stabilising role, calling upon respected chiefs like Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara and Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau to lead Fiji through crises.

Although political changes in the new millennium challenged the council’s influence, it remained committed to addressing social issues such as youth education, health, and native resource management under the leadership of past chairmen, including the late Ratu Epeli Ganilau and the late Tui Tavua Ratu Ovini Bokini.

The 2006 military coup led by Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) Commander Voreqe Bainimarama, which ousted Prime Minister Laisenia Qarase’s SDL government, marked the beginning of a tumultuous chapter for the Great Council of Chiefs.

This period culminated in the Council’s suspension in 2007 and its eventual dissolution by decree in 2012. Bainimarama, a vocal critic of the institution, had once publicly disparaged the council, remarking that its members should “go drink homebrew under a mango tree”.

A major political shift occurred following the 2022 general election, when the People’s Alliance–National Federation Party coalition, with the critical support of the Social Democratic Liberal Party, succeeded in ending FijiFirst’s prolonged dominance under Bainimarama.

As anticipated, the new Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka took the lead in reviving the Great Council of Chiefs. This began with a preliminary meeting in Bau in May 2023, followed by the council’s formal reinstatement through the passage of the iTaukei Affairs (Amendment) Act 2023 in Parliament.

During the Council’s second meeting, held in Pacific Harbour, Serua, the chiefs appointed Ratu Viliame Seruvakula — a Nasautoka chief and former senior RFMF officer — as Chairman.

This week, the council marked a significant milestone with the official reopening of its traditional meeting house, the Vale ni Bose, at Draiba in Suva.

Following two days of deliberation, Chairman Ratu Viliame announced that key issues discussed included a proposed review of the iTaukei Lands and Fisheries Commission (TLFC), the creation of an Indigenous Natural Resource Trust Fund, the establishment of an Institute of Language and Culture, and a comprehensive review of Native Land Laws dating back to 1905.

In addition, Ratu Suliano Matanitobua, the Gone Turaga na Vunivalu na Tui Namosi, and Ratu Tevita Uluilakeba Mara, the Gone Turaga na Tui Nayau na Sau ni Vanua o Lau, were appointed as Deputy Chairpersons of the council.

Perhaps the most significant consensus reached was the council’s unanimous call for the repeal of the 2013 Constitution introduced under Bainimarama’s leadership.

Ratu Viliame criticised the constitution as a major obstacle to indigenous empowerment, stating that it imposes legal barriers to the full utilisation and management of iTaukei natural resources.

Later this week, the nation will officially commemorate the life and legacy of the late Gone Turaga na Talai, Ratu Sir Josefa Lalabalavu Vanayaliyali Sukuna—widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the Council’s history.

His enduring contributions underscore that the council’s work extends beyond indigenous concerns, serving the broader interests of the nation as a whole.

This article was compiled with the assistance of information from the Ministry of iTaukei Affairs and the National Archives of Fiji.

Statesman, soldier, scholar – Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna was arguably the most influential member of the GCC. Picture: FIJI MUSEUM

The late Ratu Sir George Kadavulevu Cakobau (center left) and the late Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau (center right) during the GCC meeting in Bau during the Queen’s visit in 1982. Picture: NATIONAL ARCHIVES