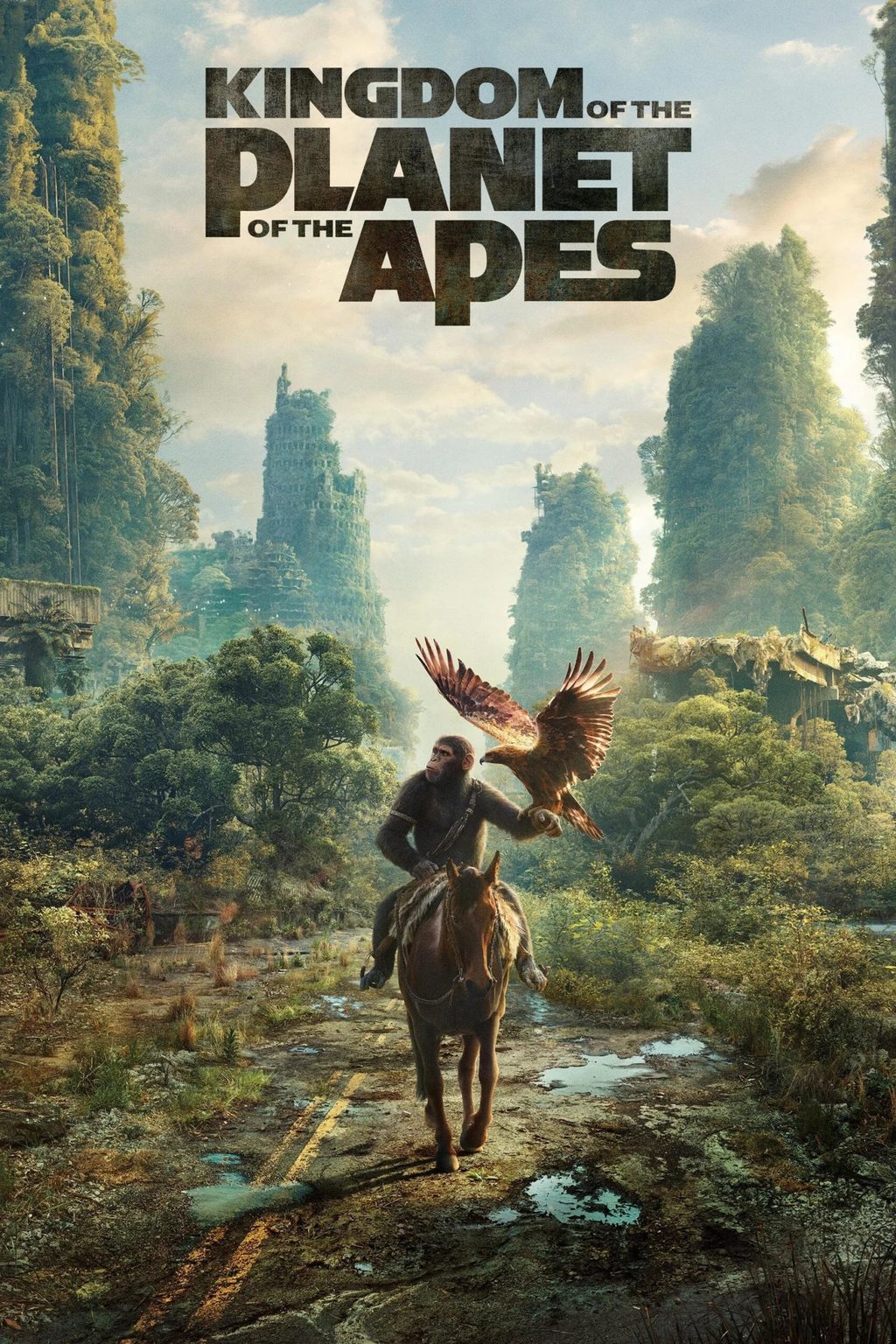

At the end of the 1968 movie classic Planet of the Apes, Charlton Heston’s character stumbles onto a beach, exhausted and battered, only to see the ruined remains of the Statue of Liberty. In that moment, he realises the shocking truth – mankind had achieved the impossible. It had destroyed itself.

It was a scene dripping with diabolical satire. The apes in the film were portrayed as the “civilised” beings, while humans were the primitive, destructive creatures. For all its science fiction packaging, the message was painfully real: when hatred, arrogance and greed rule us, our own hands will write the final chapter of our existence.

Fast-forward to today, and the film feels less like fiction and more like a prophecy. Across continents, hatred is being cultivated like a profitable crop. Lines are being drawn between races, religions, ideologies and even neighbourhoods.

And disturbingly, there are those political leaders, media voices, and vested interest groups who actively engage in stoking the flames. Simply because a divided humanity is easier to control, manipulate and profit from.

So here we are, asking the same questions Heston’s character might’ve asked if he had time to reflect:

Why can’t we be friends and live together, side by side?

What’s wrong with us?

And more importantly, where’d we go wrong and where do we go from here?

The answer doesn’t lie in the naïve hope that hatred will somehow dissipate and miraculously disappear. It lies in the deliberate choice to replace it with something more enduring and life-giving: peaceful coexistence. History and everyday life offer examples of how this can work in the real world.

When the Berlin Wall fell, one of the most surprising stories was how quickly former “enemies” began crossing into each other’s streets to talk, share meals, and trade. Why? Because once you sit across from someone, shake their hand, and look into their eyes, it’s harder to hate them. Personal connection breaks stereotyping. It doesn’t solve every problem, but it makes “us” and “them” feel more like “we.”

In Rwanda, a nation once torn apart by genocide, communities began the work of restoration by finding shared purposes – clean water, rebuilding schools, working together towards better harvests. Instead of letting history define their present, they worked toward common needs, goals and priorities. Hatred may have been the past, but survival and dignity became their future.

Violent language normalises violent thinking and violent behaviour. Nelson Mandela, who had every reason to speak with hate and bitterness after decades of imprisonment, instead chose words of unity.

“If you want to make peace with your enemy, you have to work with your enemy,” he said. “Then he becomes your partner.”

Partnerships require a level of trust and respect. In disagreements, if we avoid absolute labels (“you people,” “always,” “never”) and speak from shared humanity (“we both care about…”), words can inflame but they can also heal and lead us to a common and shared understanding and purpose.

It’s easy to think that peace is the work of governments and treaties. It should be. But it also happens in the everyday — a neighbour mowing someone’s lawn without being asked, a stranger defending someone being bullied, a customer thanking a worker who’s had a rough day.

When we create micro-moments of kindness and compassion, especially toward people we think we’ve nothing in common with, small acts can ripple outward in ways we’ll never fully see. And these can sometimes be the invisible cords bonding us to a shared vision and future.

The truth is, hatred spreads quickly like wildfire because it’s emotional, addictive and often highly profitable for those who fuel it.

But peace, when chosen deliberately, is equally contagious. The more we normalise compassion, dialogue and co-operation, the less room hatred has to grow.

In the end, Planet of the Apes was a warning: if we don’t change course, we may find ourselves staring at the ruins of what once was, wondering why we sat on the sidelines and did nothing.

The good news? Unlike Charlton Heston’s character, we still have time to turn back, to choose differently and to prove that humans can be as civilised as we imagine ourselves to be, creating enduring friendships that we were always destined for.

n By Colin Deoki is a regular contributor to this newspaper. The views expressed are his and not necessarily shared by this newspaper.

Picture: www.maltacomiccon.com

p