Fiji’s hardwood forests have spawned many blessings for centuries.

They provided the necessary raw materials for building some of the fastest renewable sea crafts that traversed the world’s biggest ocean and accessing the hundreds of islands scattered within its boundary.

Also, forests were fundamentally the indigenous people’s source of food, herbal medicines and cooking fuel, habitat for totemic animals and trees, and timber for building homes and designing traditional artefacts.

But among the Fijian forests’ most treasured value was its use as raw materials for the manufacture of revered war clubs.

People who lived in old Fiji developed and used a variety of weapons. They fashioned spears ten to fifteen feet long, powerful bows and arrows and slings for throwing stones

Although each of these had its special use and capabilities, none superseded the club in acclaim and prestige.

“Whether his tribe was at war or at peace, he (the warrior) was seldom without it, for until the latter half of last century no Fijian left the precincts of his house unarmed,” says historian, R. A. Derrick, in “Notes on Fijian Clubs”.

“Whenever he left his village, even to work in his garden, he carried his club on his shoulder; and should he meet a man in the path, the club remained in that position, at the alert, until on friendly recognition both men lowered their weapon in greeting.”

While the whales tooth reigned as the most valuable traditional item and tanoa as a commodity associated with sacred rituals, the war club, though stained with blood and the horrors of war, had its own peculiar appeal and charm.

Through the war club, kingdoms were forged and strengthened and power changed hands between the victor and the crushed.

It is said that in peace times, when a man visited another village, he would never go unarmed for fear that villagers would say, “He despises us. He comes without weapons.”

Hence, the warrior always carried a dress club out of necessity and courtesy.

Clubs a symbols of great craftmanship

When explorers, traders and colonials settlers came to Fiji, they were amazed by the standard of craftsmanship used in the design of war clubs.

Up until the end of British colonial rule, it was deemed the most fascinating souvenir that truly encapsulated the Fijian way of life.

Art collectors and British officials often took these war tools with them when they returned home. The savagery associated with the club gave it a special character and identity that captivated foreigners.

Today, many war clubs from the 1800s find themselves inside glass exhibit cases of many of the world’s museums.

For instance, the 150-year-old Metropolitan Museum of Art on New York City’s fabled Fifth Avenue, has war clubs and several other artefacts from Fiji.

These items are located in a 40,000-square-foot section called “The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing” which holds a collection of art from Africa, Oceania and the Americas.

According to Wikipedia records, the Africa, Oceania and the Americas collection ranges from 40,000-year-old indigenous rock paintings, to a group of 15-foot-tall (4.6 m) memorial poles carved by the Asmat people of New Guinea and a priceless collection of ceremonial and personal objects from the Nigerian Court of Benin donated by German art dealer Klaus Perls.

Some Fiji wooden artefacts at The Met, including war clubs, are totokia, dave ni waiwai, masi kesa, culacula, sali, vunikau, vulibuli, vonotabua, iulatavatava and sedre ni waiwai.

The types and styles of Fijian war club come in an exceptionally wide range. High degrees of skill and patience were taken while fashioning clubs that were to be used by chiefs.

Although certain types appear to have been more in favour than others, there was room for personal choice in pattern, miner details, decorative and finish.

The most elaborately designed clubs, called culacula, were for priests and chiefs. They delivered blows with the thin edge of their blades and had the ability to cut or snap through bones rather than simply shattering it.

“The Tongans may have developed them as a shield-club when they first encountered Fijian war arrows in the mid to late 1700s,” noted a Fiji Museum online article.

“Chiefs and priests, who would stand at the front of the war party, were particularly at risk of flying “missiles”.

Anatole von Hugel was famous for amassing a large collection of “Fijian artefacts of unsurpassed quality”. He took them back with him to Britain on his return home.

After being appointed as the inaugural director of the new Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropoly, he donated his collection from Fiji to the institution, many of them war clubs.

Sir Arthur Gordon added to the Fijian collection at the Cambridge Museum.

While today’s clubs can be largely spotted during dances and traditional ceremonies such as funerals of high chiefs, in the early days, as you’d imagine, the wooden artefact was a common sight.

Its familiarity and prevalence never made it unimportant. In fact, in the eyes of both indigenous Fijians and curious white men, the clubs had a special place in people’s minds and imagination.

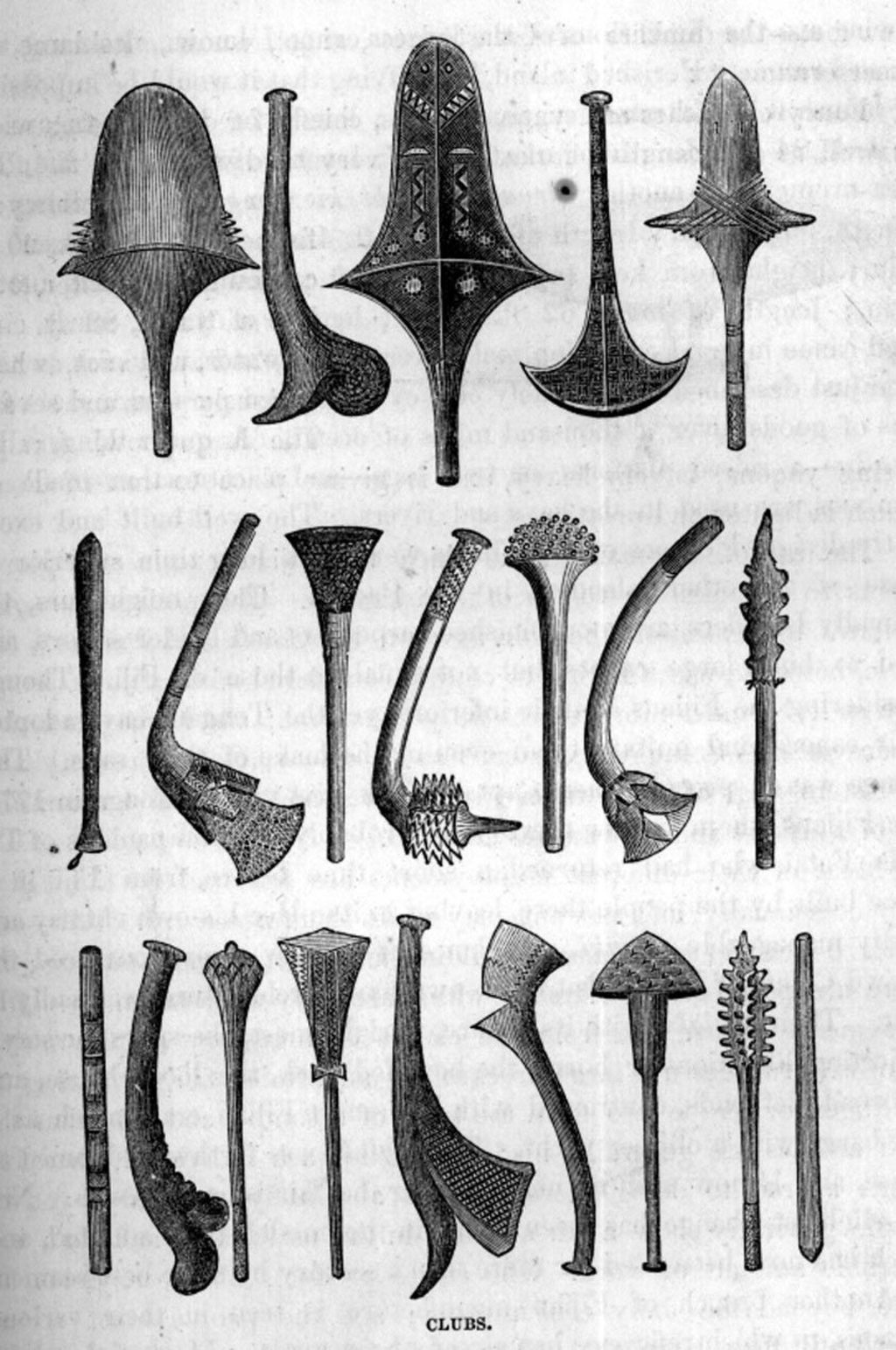

Before the arrival of cameras, the white man made meticulous freehand sketches of them while recording information in the pages of history books.

Among the earliest published sketches of Fijian clubs were those that accompanied the Narrative of Dumont d’Urville’s first voyage to the Pacific (1926-29), and in Fiji and the Fijians by Thomas Williams (London, 1858).

D’Urville was in Fiji waters for only a short while between May and June, 1826, and his artist recorded only a few weapons. Nevertheless, his sketches are believed to be reasonably accurate when compared to William’s drawings.

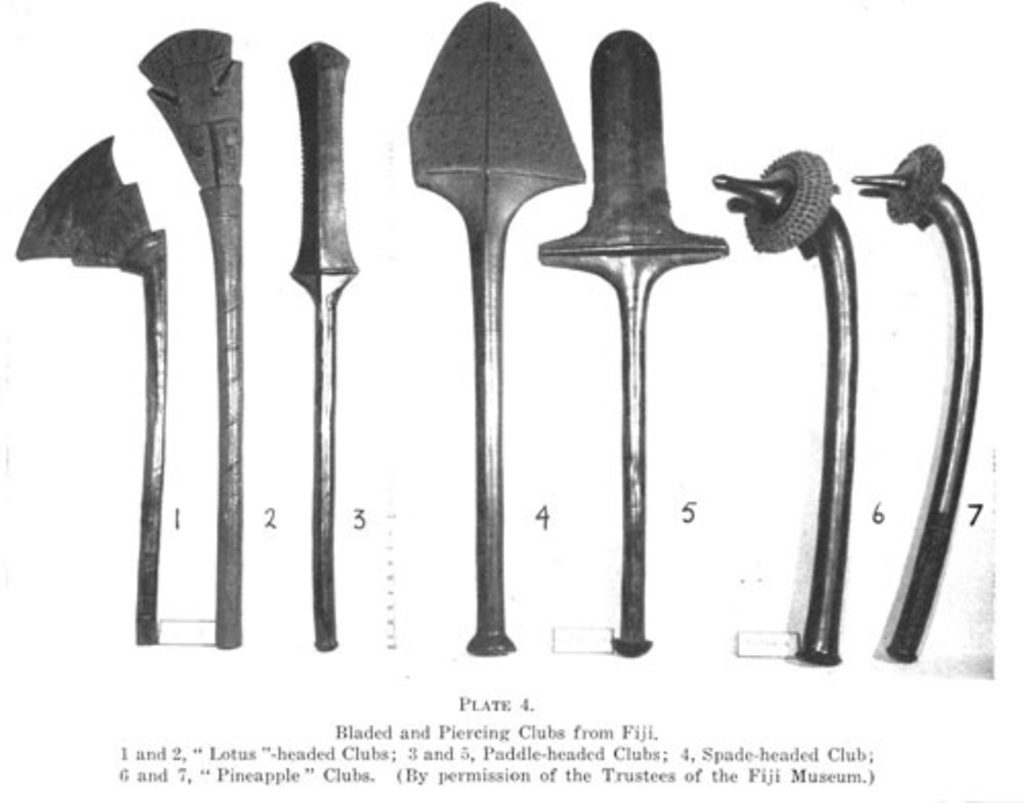

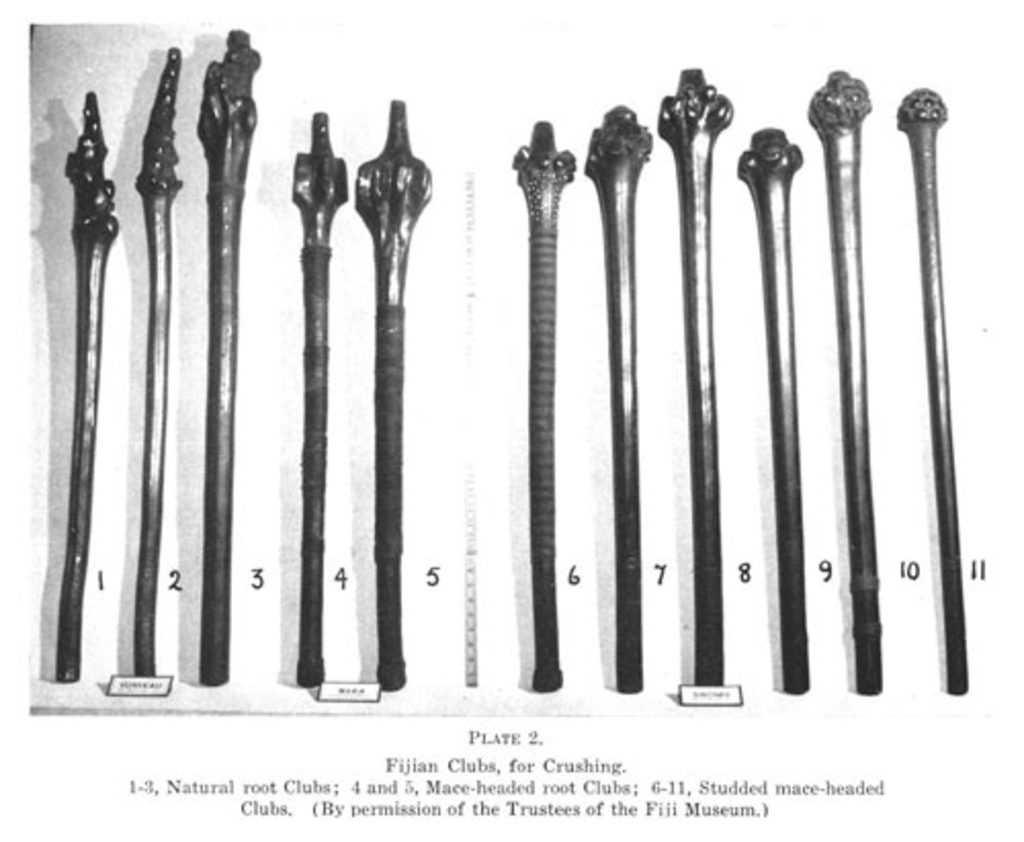

All sketches and later photos show that ancient Fijians classified their clubs with a good sense of appreciation of their use and design.

One of the well-known writers to classify traditional Fijian clubs was R.A Derrick who was able to categorise them into eight distinctive groups based on their purpose and form.

He classed them as striking clubs, crushing clubs, cutting clubs, piercing clubs, missile or throwing clubs, dress or token clubs, ceremonial clubs and dance clubs.

According to Derrick, “nature and art” both influenced the fashioning of certain types of war club.

“Some being formed from the butts of uprooted trees, the heads of others being shaped in the growing tree and requiring attention for months and even years,” noted Derrick.

“On the other hand many were carved from slabs of hardwood split from the tree; others again were simple bludgeons, cut from the heartwood of selected trees and balanced with precision.”

War club designs

Generally, Fiji war clubs were neither too heavy nor too light.

Historical records show this made them effective and easy to use during battles and at the same time, this provided them with an “inflicting blow”.

Furthermore, each type of club was designed to specifically suit its user’s physical built, status in the community and personal taste, among other reasons.

On the other hand, ceremonial clubs were largely weightier than war clubs because they were made for carrying on the shoulders and not for fierce fighting.

Because ceremonial clubs were not used for crushing and striking, they had carvings on them using fine and intricate patterns. Some were heavily decorated with inlaid bones and others – with “primitive decorative materials”.

According to an online article on www.new-guinea-tribal-arts.com Fiji had “more styles of native weapons than anywhere else in the Pacific”.

This has been attributed to the fact that Fiji experienced “a long history of warfare” and “rampant ceremonial cannibalism”.

Another online article on Pitt Rivers Museum website concurred that the type of club used in Fiji was “not surprising” given the “nature of Fijian society”.

“Warfare was part of everyday life on the islands where by the early 1800’s chaos reigned with local feuding and increasingly bloody civil wars becoming commonplace,” the article noted.

“The different type of club illustrates that demand was great. The highly diversified array of Fijian war clubs reveals that the Fijian had devised a weapon for every type of stroke. Within the founding collection the variety of club type is evident.”

To understand how war clubs were used, it is important to know a brief history of Fijian warfare.

An expert and anecdotal commentary of Fijian warfare explained the state of affairs in Fiji to the end of the 19th century this way – that in most societies, tales of war pervaded “popular culture because they are rare breaks from long stretches of peace”.

In Fiji, according to the commentary, the case was a bit different!

“Narratives of peace were told amidst an almost ceaseless series of family feuds and regional skirmishes,” it read.

“Account after account show how Iliadic wars rose from infidelities. Battles did feature certain theatrical elements and some clubs were just used as representations of symbolic power, but men always kept a club on their person for personal safety rather than aesthetics.”

Wars were not only against other neighbouring tribes and clans. They were also against invading foreign forces like the Tongans. And as such, the design of some Fijian and Tongan clubs later shared a few similarities.

However, Tongan clubs were easily distinguished by the zigzag motifs carved on their surfaces. Clubs that had human and animal figures carved on them were believed to have given their handlers supernatural powers and protection.

Others were elaborately designed with carvings inlaid with shells and whales tooth to signify rank, royalty and wealth.

Uses of Fijian clubs

A small range of clubs were used for ceremonies or as family inheritable antiques.

An online commentary noted that by the 1880s, “war occupied the entire male population of Fiji”.

As a result young boys were trained in the wielding of weapons from early childhood and only being given a real man’s name once they had killed an enemy.

Most battles started with missile weapons including showers of arrows and sling stones, spears and throwing clubs. However, it was only when opposing warriors engaged each other with their heavy, two-handed clubs that casualties became serious.

Among the earliest published sketches of Fijian clubs were those appearing in the Atlas Pittoresque accompanying the Narrative of Dumont d’Urville’s first voyage to the Pacific (1926-29), and in Fiji and the Fijians by Thomas Williams ( London, 1858).

D’Urville was in Fiji waters on this occasion only for a short time from May to June, 1826. In his drawings he recorded only a few weapons. The sketches were reasonably accurate nevertheless.

In Williams’s book, on the other hand, some of the twenty-one Fijian clubs illustrated were somewhat “distorted and out of proportion”.

Since the 1800s, war clubs had travelled outside of Fiji. Today, a wide range has found new homes in many museums of the world. Others remain in the hands of private collectors.

Due to the interest around them, some of these clubs now fetch considerable high prices. One BBC video put the cost of one totokia club, sometimes referred to as the “pineapple club”, at around 8000 pounds.

“It (club) is made from an indigenous wood called vesi, which is incredibly tough. This club has taken a bit of a battering over the years, but it is equally very beautifully carved. Additionally, over the last few years, the market for native objects for these has shot up. This piece would currently fetch around £8,000,” the video noted.

Meanwhile, in a www.bbc.co.uk posting, the media outlet said Fijian war clubs were often “buried with chiefs or great warriors to accompany their spirit to the after world”.

Amongst all the Pacific cultures, Fiji has shown perhaps the most innovation in the development of efficient and fearsome weapons.

A wide range of weapons was made and as a consequence the “i-wau”, or depending on dialect “i-ravu” (clubs) of various types were favoured. The totokia’s unique design, for example, has made it a highly sought after wooden artefact.

It is different from other club designs in both purpose and fashion. Some believe it may possibly have been developed under “European” or “other external influence”. However, there is no evidence to support such a hypothesis.

The “pineapple” club was among those illustrated in Dumont d’Urville’s Atlas. It was depicted as having a “massive globular head”, elaborately carved in traditional pattern suggestive of the fruit of the pandanus (vadra) or the pineapple, but not necessarily derived from these.

It was not used as other war clubs were, for delivering a shattering blow. The operative part was the pointed “beak,” which with the globular head was cleverly designed to pierce the victim’s skull, inflicting a fatal wound.

To achieve this purpose no wide arm-swinging was necessary. The mass of the head gave sufficient momentum when the club was moved through a short arc.

The totokia was therefore favoured for assassination, since the blow could be delivered from behind, without the momentous swing that could warn the victim.

Some museum collections have shown that Fijian weapons sometimes had distinctive notches, drilled holes or even human teeth cut or inlaid into them. These were done to allow a warrior to ‘keep a scoresheet’ of his triumphs in combat.

Most of Fiji’s war clubs, perhaps with the exception of the throwing, bladed and piercing varieties were generally for heavy and blunt blows delivered at close range and often targeted at the skulls.

Hence, they would very often inflict blunt force trauma caused by a forceful impact to the body without necessarily penetrating it. To enable this, the wood used for weapon design would have been heavy and hard.

The resulting blows easily caused contusions, lacerations and fractures that resulted in blood loss, tearing of soft body tissues, organ failure and injury, the splintering of bones and ultimately death.

To say that Fiji’s tribal wars and the use of war clubs were merely part of Fiji’s history may seem like an understatement. In fact, it was intrinsically entrenched in the Fijian way of life.

Therefore, in olden days, club-yielding warriors had an important place and role in society. They enabled chiefs to wrestle and hold power and therefore were an integral parcel of the traditional Fijian leadership structures.

Warriors were also so important to chiefs that they were often buried with their wives and their weapons, a rite normally accorded to royalties.

War clubs were inextricably linked to the old religion and its deities who demanded human sacrifices and war.

This indirectly meant that religious practices also had a hand in influencing the frequency of lethal attacks and the weapons needed to make those killings.

Hence, revenge and hatred did not end when the enemy died, but were, along with religion, key reasons why cannibalism persisted.

“. . . . it must be lamented that their worst crimes are sanctioned, and are continually promoted, by their divinities, who are not only cannibals and adulterers like themselves, but have pleasure in those that are such,” wrote Reverend John Hunt in 1858.

Before there was a raid or war Fijians engaged in a range of religious ceremonies where priests consulted with their traditional deities in an attempt to secure success in battle. In some cases, divine intervention was sought to make the weapons of enemies virtually harmless to warriors’ bodies.

- Part 2 Next week

Fiji’s bladed and piercing clubs.

A drawing of Fijian war clubs. Picture:line.77qq.com

The totokia (pineapple club) for piercing and puncturing holes. Picture:WWW.AUCKLANDMUSEUM.COM

The Fijian war clubs are designed based on their purpose. Picture:WWW.GREENDRAGONSOCIETY.COM

A depiction of Fijian warriors with their war clubs and spoils. Picture:WWW.GREENDRAGONSOCIETY.COM

Fijian crushing clubs Picture:JPC.AUCKLAND.AC.NZ

Fijian war artefacts on display in a museum overseas. Picture:WWW.TRIPQADVISOR.COM