Education reform has been a challenge for our governments, with efforts to strike the right balance often proving elusive.

A glance through any political party’s election manifesto reveals it as a top priority. Yet for any newly elected government, even the smallest misstep in education policy can become its Achilles’ heel.

The education sector in Fiji is crucial in achieving its socio-economic objectives. An efficient and relevant curriculum combined with a well-trained cohort of educators, supported by the provision of sufficient and adequate level of resources is bound to have enormous positive reverberations across the nation.

Without delving too deeply into Fiji’s broader political history, a look at the more recent past offers significant insight in why education reform in again on the national agenda.

Prior to the 2014 elections, Voreqe Bainimarama’s interim government undertook an extensive overhaul of many of the country’s state institutions and public services.

Among the most significant was a comprehensive restructuring of the education system. This included a complete curriculum revamp, the removal of certain external examinations and the introduction of new ones, as well as a series of contentious decisions.

These ranged from limiting the involvement of teacher unions in shaping education policy to enforcing a top-down reorganisation of operations within the Ministry of Education—the largest ministry in government.

Initially, these reforms were well received. When Bainimarama secured victory in the 2014 general election and became Fiji’s sixth prime minister, buoyed by the popularity of his FijiFirst party, his government escalated its reform agenda.

Among its most significant achievements were the introduction of tuition-free education and subsidised bus fares for students – initiatives that have since been upheld by Rabuka’s Coalition Government.

While the Bainimarama-led reforms significantly broadened access to education and improved affordability, they fell short of addressing deep-rooted, systemic issues within the sector.

The government’s decision to sideline teacher unions and adopt an almost confrontational stance towards school management boards—many of which are religious organisations responsible for running over 90 per cent of Fiji’s schools—intensified ongoing challenges, particularly those around teacher welfare and deteriorating infrastructure.

After successfully forming government in the wake of the 2022 general elections, which resulted in a hung parliament, Sitiveni Rabuka and his coalition partners launched an ambitious reform agenda, effectively reversing many of the previous administration’s policies.

In the area of education, a major step forward came in October last year with the announcement of the establishment of the Fiji Education Commission, tasked with leading a comprehensive review of the existing education framework.

As part of this process, the Ministry of Education has initiated nationwide consultations on the review of the Education Act 1966, creating space for teachers, students, and other stakeholders to voice concerns and share proposals for improvement.

There is growing optimism as Minister for Education Aseri Radrodro has recently confirmed that the curriculum review is expected to be finalised by the end of this year, with a new National Curriculum Framework scheduled for rollout at the start of 2026.

Contributing to this national effort, the University of Fiji (UniFiji) has submitted a comprehensive report to support the review and reform process. The submission not only highlights the challenges currently confronting the education sector but also proposes innovative and practical solutions to address them.

In the report which was delivered last week to the Ministry of Education, the university argues that the present Education Act of 1966 “no longer reflects the realities of our classrooms, the rights of our children, or the ambitions of our nation”.

Vice-Chancellor Professor Shaista Shameem emphasised that Fiji now stands at a critical juncture.

“Legislative gaps are not minor, they are systemic. We must realign the entire education system with contemporary expectations and our international obligations. Every child deserves more than access; they deserve a system that protects, empowers and uplifts,” she said

Compulsory schooling to 18

At the heart of the submission is a call to enforce compulsory, free schooling from age five until pupils complete Year 12—or reach their 18th birthday, whichever comes first. Parents and guardians would carry a statutory duty to enroll children and ensure regular attendance, with clearly defined penalties for non-compliance.

To bolster enforcement, the report proposes the appointment of “Attendance Watch Officers” empowered to patrol public spaces during school hours, return absent children to class or home, and liaise with school leaders and social-welfare officials. The university argues that stronger attendance monitoring would also help curb the rise in drug-related and sexual offences involving minors.

A ‘cradle-to-career’ Act

In a bid to eliminate policy fragmentation, UniFiji recommends merging the Education Act 1966 with the Higher Education Act 2008 to create a unified “Education Act” spanning early childhood through tertiary level.

The Higher Education Commission would become a dedicated department inside the Ministry of Education, staffed by experienced educators to ensure consistent governance and seamless oversight “across all levels, all islands, and all providers”.

Curriculum overhaul every two years

The report calls for a “robust and relevant” national curriculum anchored in critical thinking, digital and financial literacy, climate education, civic responsibility, and basic legal knowledge. Starting in primary school, learning areas should be age-appropriate, inclusive, culturally responsive and reviewed biennially by an independent, permanent Education Commission.

Professor Shameem stressed that frequent reviews are essential.

“The pace of technological, social and environmental change means a curriculum can become outdated in months, not decades. Our learners must be future-ready.”

Safe schools and well-being

The submission places child protection front and centre. Schools would be legally obliged to provide safe infrastructure, emergency-preparedness plans and free access to trained counsellors or psychologists. Free breakfasts or lunches for every pupil are mooted to guarantee “at least one nutritious meal a day”, while early-intervention and catch-up schemes would identify struggling students before they drop out.

Annual school inspections, long dormant, would be reinstated, with breaches punishable by fines, licence suspensions or prosecutions. Clear offences, ranging from operating unregistered institutions to obstructing inspectors, are enumerated to ensure swift enforcement.

Teachers and governance

UniFiji argues that high-quality teaching is the linchpin of reform. It proposes revised standards for teacher qualifications, registration and performance appraisal, alongside the re-introduction of school inspectors.

At governance level, a streamlined reporting structure would make boards and principals more accountable for performance, finances and child welfare.

Independent watchdog

To track progress, the university recommends an independent authority, potentially the re-vamped Education Commission, to collect and publish data on attendance, equity, learning outcomes, infrastructure and budget use.

Transparent, evidence-based reporting, it says, will underpin continuous improvement and public confidence.

Alignment with national and global goals

The submission explicitly links UniFiji’s recommendations to Fiji’s 2013 Constitution, the right to education under international law and the Government’s national-development plans.

“This is a national investment in a resilient, inclusive, knowledge-based future,” Professor Shameem said.

“Our children cannot wait another generation for legislation that truly works.”

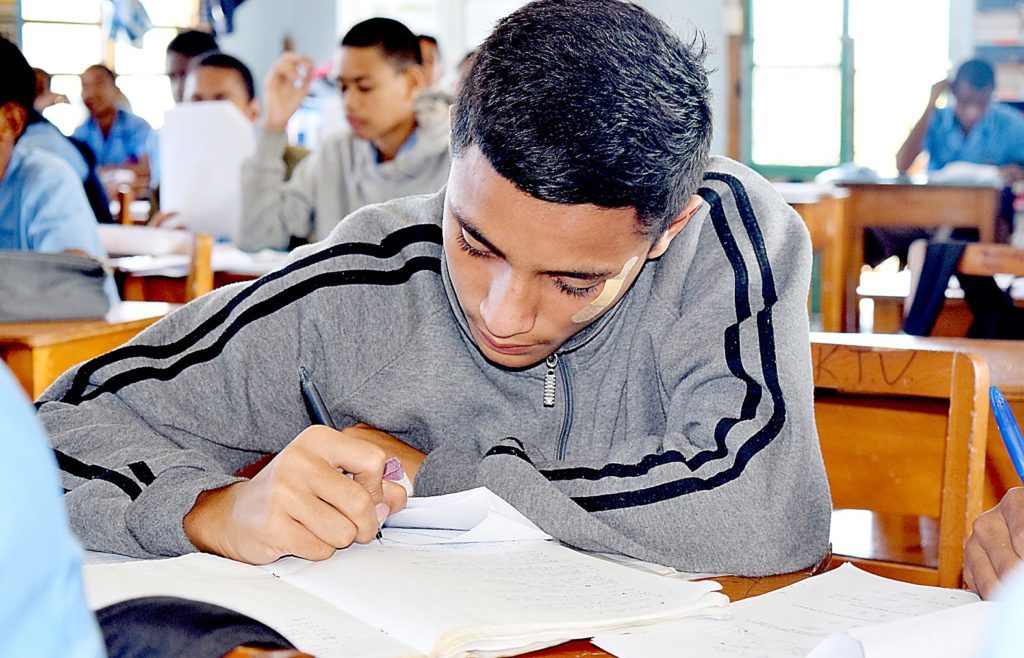

Primary school teacher George William with his students. Picture: FILE.