For most Fijians, the death of Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara in 2004 marked the end of an era.

He was not only Fiji’s founding prime minister and a former president, but also the Tui Nayau, Tui Lau and Sau ni Vanua ko Lau, a paramount chief whose authority and influence stretched across generations, islands and institutions.

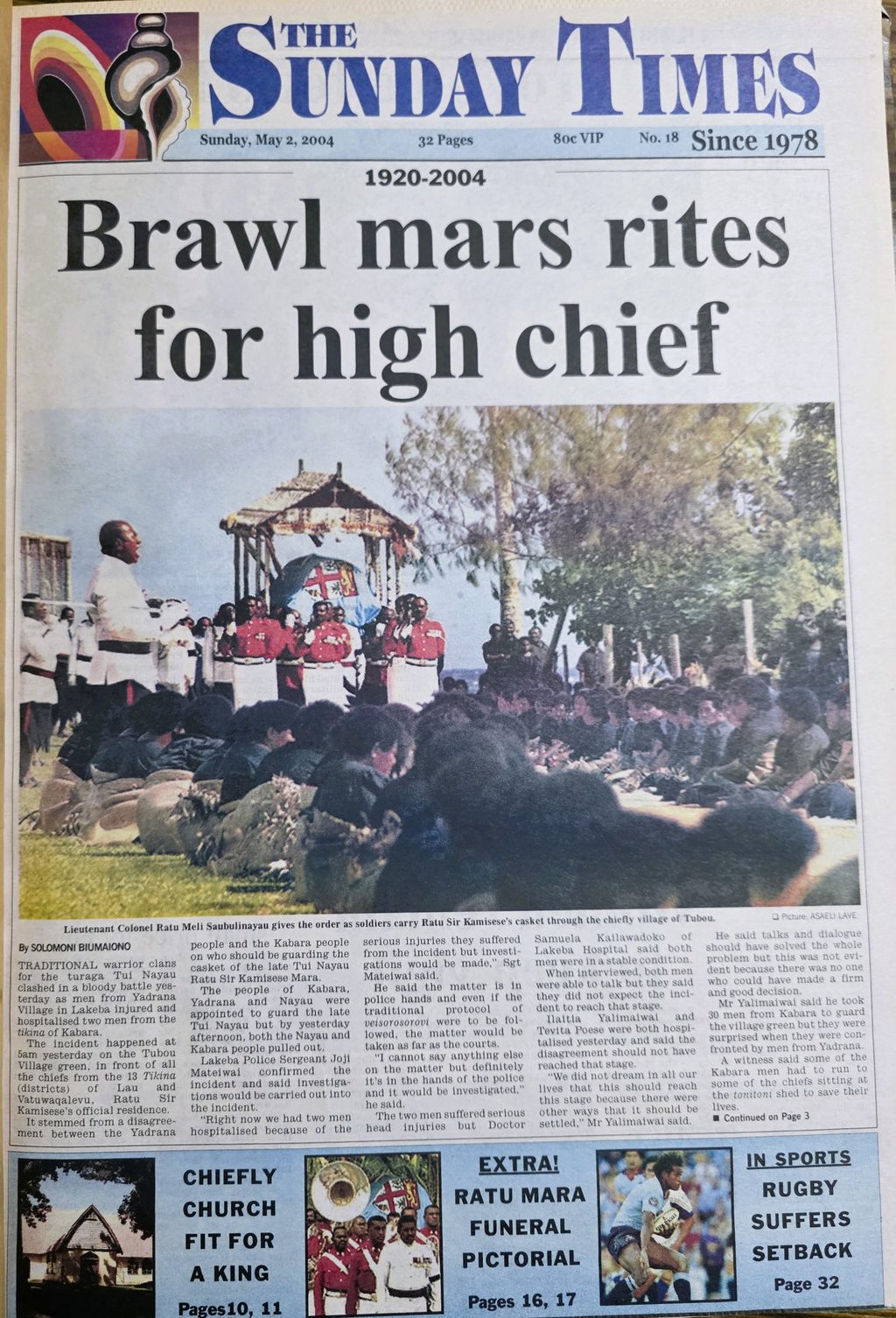

But amid the solemn rituals, ancient protocols and collective grief that accompanied his burial on Lakeba Island, a violent confrontation unfolded, which largely remains unresolved more than two decades later.

For Tevita Poese of Tokalau Village on Kabara Island, the events at Tubou Village during the chiefly funeral are not distant history because they live on in his body, his health and his spirit.

“I went to Lakeba knowing exactly why I was there.

“We all came knowing our roles, our obligations and our responsibilities to our late paramount chief.”

As a man of Kabara, Mr Poese attended the funeral as part of a long-established cultural duty.

In Lauan tradition, every island and clan has a defined role during major chiefly ceremonies and for Kabara, that role has always been clear.

Sacred roles, deeply held

“In terms of the yadra which is the guarding of the late chief’s body and the chiefly grounds, it was traditionally known that this sacred duty rested with the men of Yadrana and Kabara.”

The men of Kabara are recognised as bati balavu, the warriors responsible for guarding the outer precincts of the chiefly area.

The men of Yadrana, meanwhile, are entrusted with the inner sanctuary, where the body of the paramount chief lies.

“That was the role I had always known,” he said.

“I had done it many times before alongside the men of Yadrana. There had never been disagreements or conflict. We always worked together.”

Yet during the mourning period for the late Ratu Mara, something changed.

Despite the shared grief and the presence of Lauans from every island in the group, tensions emerged over who held authority over the vigil.

What should have been a sacred duty descended into confusion, confrontation and violence.

“To this day, I cannot say for sure what the root cause was.

“What happened there was sudden. Those of us from Kabara had absolutely no idea what the issue was.”

The clash at Tubou

Media reports at the time described how the dispute escalated into a physical confrontation involving traditional weapons.

Police were forced to intervene, with reinforcements deployed to Lakeba as tensions threatened to spread.

Several men were beaten and Mr Poese was among those seriously injured.

“Two of us were badly hurt,” he recalled.

“Another gentleman later died from his injuries a year later.”

Now believed to be the last surviving victim of the beating, Mr Poese says the consequences of that day have followed him into old age.

Once active and firmly rooted in life on Kabara, he now lives in Suva to access medical care.

“My health has been getting worse.

“The doctors have identified issues that I believe are linked to what happened back then.”

The physical pain, he explained, comes and goes, but the emotional toll has never eased.

“It’s the spirit of division that hurts the most.

“That is what continues to affect me today.”

A wound left unattended

Perhaps more painful than the injuries themselves is what Mr Poese describes as the absence of reconciliation.

“To this day, as far as I am aware, there has been no discussion, no reconciliation of any kind between the bati clans involved.”

More than 20 years on, the matter remains unaddressed within the vanua, leaving unresolved hurt between clans that once stood shoulder to shoulder in service to Lau.

“This issue might be old, but the wounds are still fresh in my mind and body.”

He emphasised that the reconciliation he was referring to was not about blame or punishment.

It is about acknowledgement, clarity and restoring harmony within the Lauan community.

A new dawn for Lau

The installation of Ratu Tevita Uluilakeba Mara, son of the late Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, as Tui Nayau has renewed hope that the time for dialogue has finally arrived.

“With our new paramount chief, it is a new dawn for Lau.

“I believe it is time we formally acknowledge what happened in 2004 and put it behind us.”

He believes reconciliation would not only bring personal closure but also serve a vital cultural purpose.

“As a vanua, we need to clearly define and clarify our traditional roles and duties,” he said.

“This is to ensure that nothing like this ever happens again.”

Mr Poese has suggested that such discussions could be taken to the Lau Provincial Council, possibly through structured education or refresher sessions on traditional responsibilities, particularly for younger generations.

“This is vital that the youth must know who we are, where we stand, and what our responsibilities are.”

Respect for a great chief

Despite the pain associated with the events of 2004, Mr Poese speaks of Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara with deep admiration and reverence.

“He was chiefly in every sense of the word.

“From his presence to his actions as a leader of the vanua and as prime minister.”

Growing up, Mr Poese attended many events where Ratu Mara was present, both in Lau and on Viti Levu and he remembers a leader who understood the struggles of people from remote islands and worked to uplift them.

“It saddens me that such conflict occurred during his funeral.

“That was not the spirit of the man he was.”

Ratu Mara, he added, was a leader who believed in consensus and dialogue, which were values that were tragically absent on that day in Tubou.

“If only things had been handled with perspective rather than violence.

“We should have chosen dialogue. That is wha3t he (Ratu Mara) would have wanted.”

A message for the future

As Lau moves forward under its new paramount chief, Mr Poese hopes his story serves as a lesson not just about tradition, but about humanity.

“To the youth, I will only say uphold your links to the vanua, serve God faithfully, and respect each other,” he said.

“Above all, love is most important.”

Reconciliation is not a political act or a mere symbolic gesture, it is necessary to ensure genuine healing, not just for those who were affected by the altercation at Tubou, but more importantly for the future generations of Lauans who will one day stand guard at the funerals of great chiefs and entrusted with duties that have been shaped over the centuries.

“It is time for us to sit together, seek forgiveness, and move forward as one.”

Men of Yadrana stand guard during the installation ceremony oi the Tui Nayau last year. Picture: SUPPLIED

Traditional warriors of the Tui Nayau from Yadrana in Lakeba during the installation ceremony of Ratu Tevita Uluilakeba Mara at Tubou last year. Picture: SUPPLIED

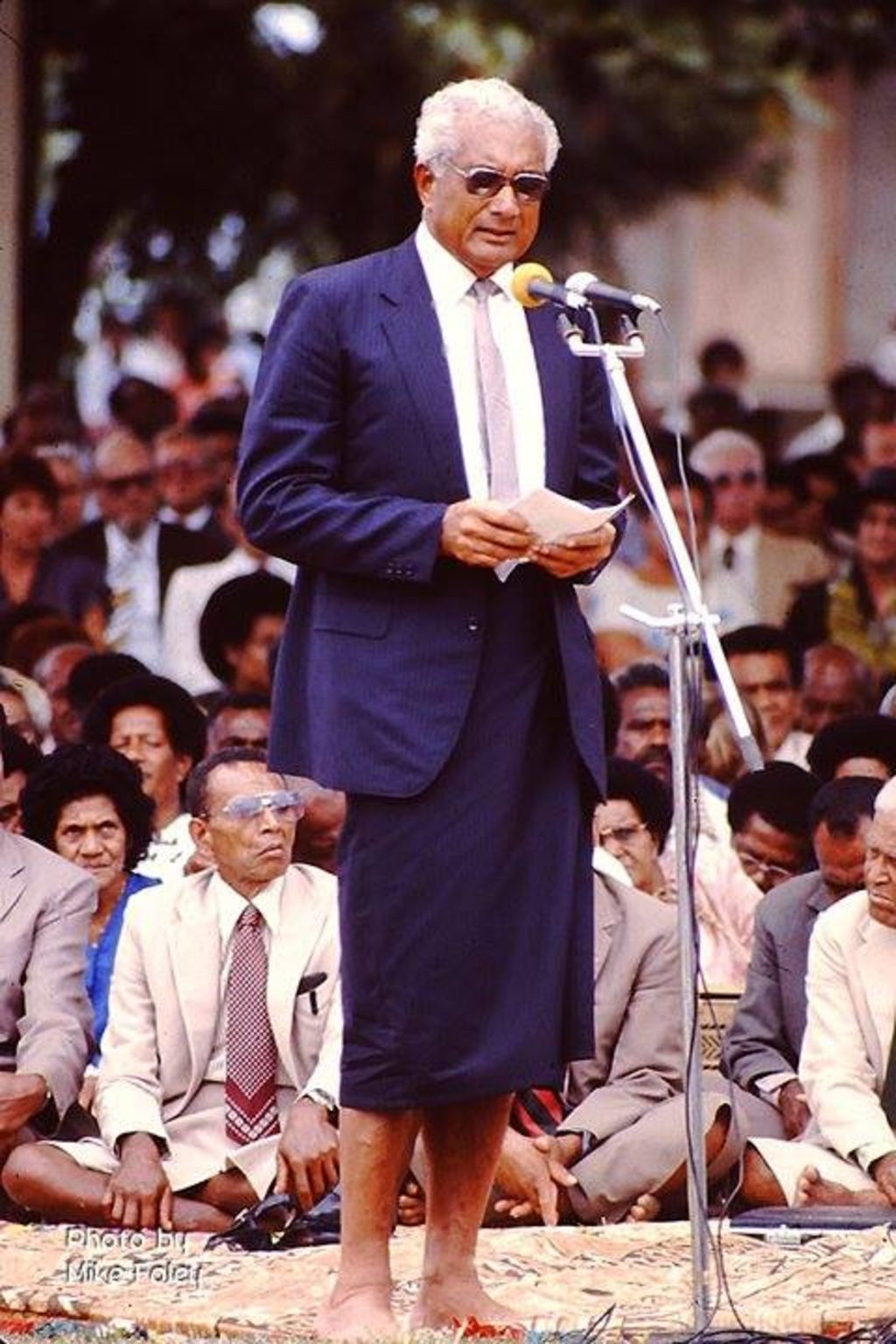

The late former prime minister and Tui Nayau, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara delivers his opening remarks during a meeting of the Lau Provincial Council. Picture: SUPPLIED

Adi Koila Mara Nailatikau, daughter of the late Ratu Mara escorts her mother, the late Roko Tui Dreketi, Adi Lady Lala Mara during the chiefly funeral at Tubou, Lakeba. Picture: SUPPLIED

Arial view of the chiefly village of Tubou on the island of Lakeba in Lau. Picture: FIJI GOVERNMENT

Below: The Sunday Times front page story on May 2, 2004 that broke the story of the confrontation in Tubou. Picture: FT FILE

Above: RFMF pallbearers carry the casket of the late Tui Nayau onboard the government vessel, Iloilovatu. Picture: FT FILE